[ad_1]

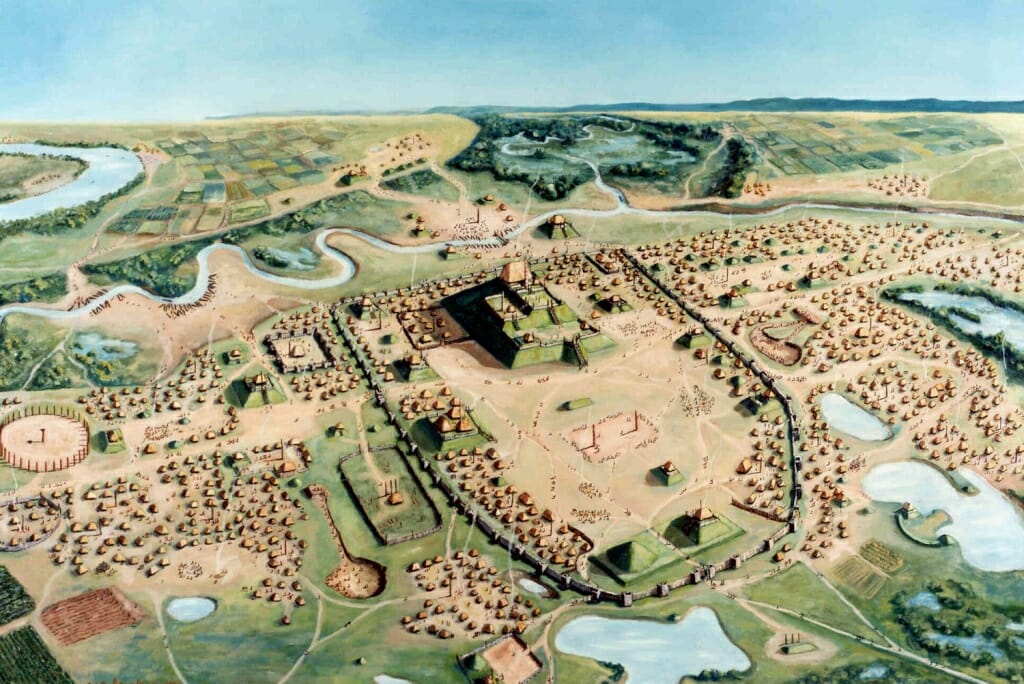

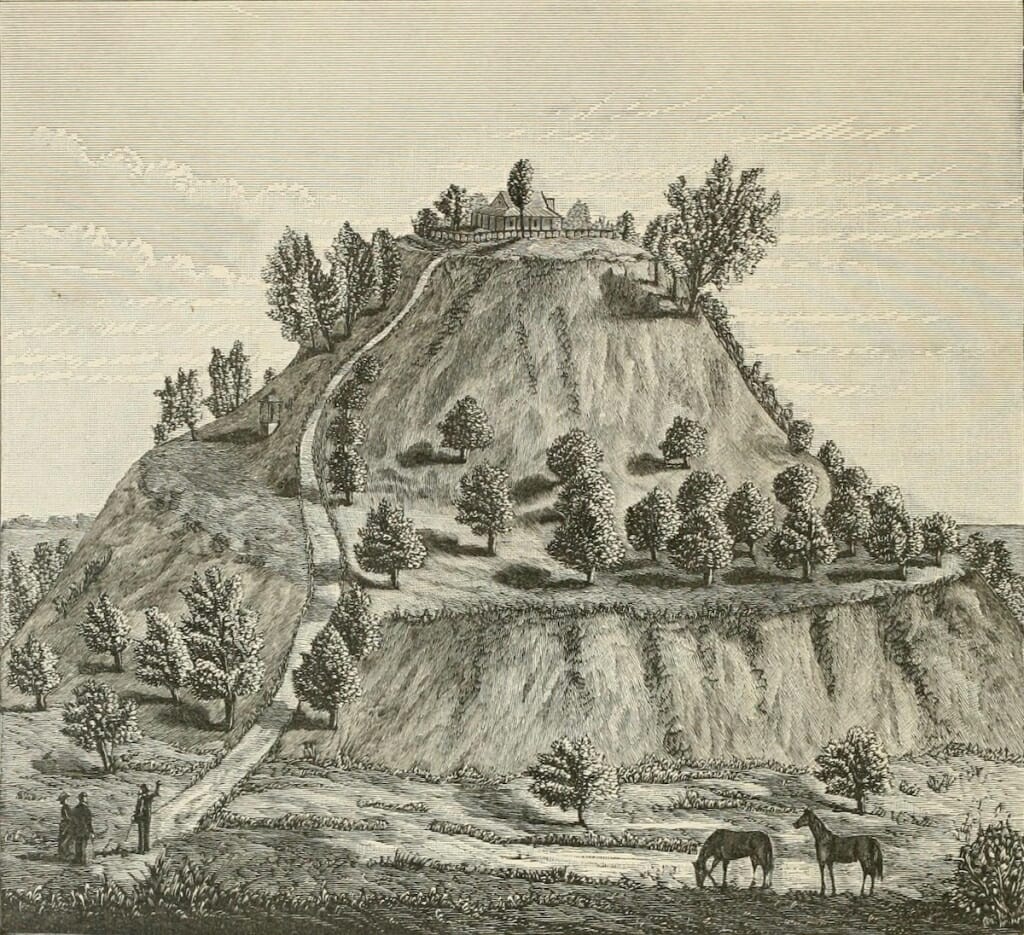

A painting of the Cahokia Mounds State Historic Site by William R. Iseminger. At the top left, Horseshoe Lake, where the main sediments provide a chronological overview of the Mississippi floods, is visible. Courtesy of William R. Iseminger

A new study shows that climate change may have contributed to the decline of Cahokia, a famous prehistoric city near St. Louis. And it's about old human poop.

Posted today [Feb. 25, 2019] In the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the study establishes a direct link between the evolution of the population size of Cahokia, measured using a single fecal register and environmental data showing signs of drought and floods.

"The way to rebuild the population usually involves archaeological data, which are distinct from the data being studied by climatologists," says lead author AJ White, who has completed the work as a postgraduate student. at California State University in Long Beach. "One involves excavations and a study of archaeological remains and the other of lake cores. We unite these two factors by examining both types of data from the same lake cores. "

Last year, White and a team of collaborators – including his former adviser Lora Stevens, professor of Paleoclimatology and Paleolimnology at California State University in Long Beach and the University of Wisconsin – professor of science and technology. Anthropology at the University of Wisconsin – Madison Sissel Schroeder – have shown that they can detect human cocoa signatures. in lake carrot sediments collected in Horseshoe Lake, not far from the famous mounds of Cahokia.

These signatures, called fecal stanols, are molecules produced in the intestine during digestion and eliminated in the stool. When the inhabitants of Cahokia pooped on the mainland, part of it would have sunk into the lake. The more people lived and did their needs, more stanols were present in the lake sediments.

UW-Madison anthropology professor, Sissel Schroeder, describes a piece of investigative equipment while she welcomes grade six students visiting Aztalan State Park, a prehistoric Amerindian site. located near Lake Mills, in 2018. Photo: Jeff Miller

Because the sediments of a lake accumulate in layers, they allow scientists to capture snapshots of time throughout the history of an area through sediment cores. The deeper layers are formed earlier than the layers found above and all the material of a layer is about the same age.

White found that fecal stanol concentrations in Horseshoe Lake increased and decreased in the same manner as estimates of the Cahokia population based on more established archaeological methods.

Schroeder, a scholar from the Cahokia region, explains that the excavations of the houses of Cahokia and its surroundings show that the human occupation of the site has intensified around 600 AD and that 39, in 1100, the city of six square miles reached its peak of population. At the time, tens of thousands of people called him at home.

Archaeological evidence also shows that in 1200, the population of Cahokia was declining and that the site had been abandoned by the Mississippian inhabitants, who built a mound, at 1400.

Scientists have uncovered a number of explanations for its possible abandonment, including social and political unrest and environmental change.

AJ White Photo of Danielle Macdonald

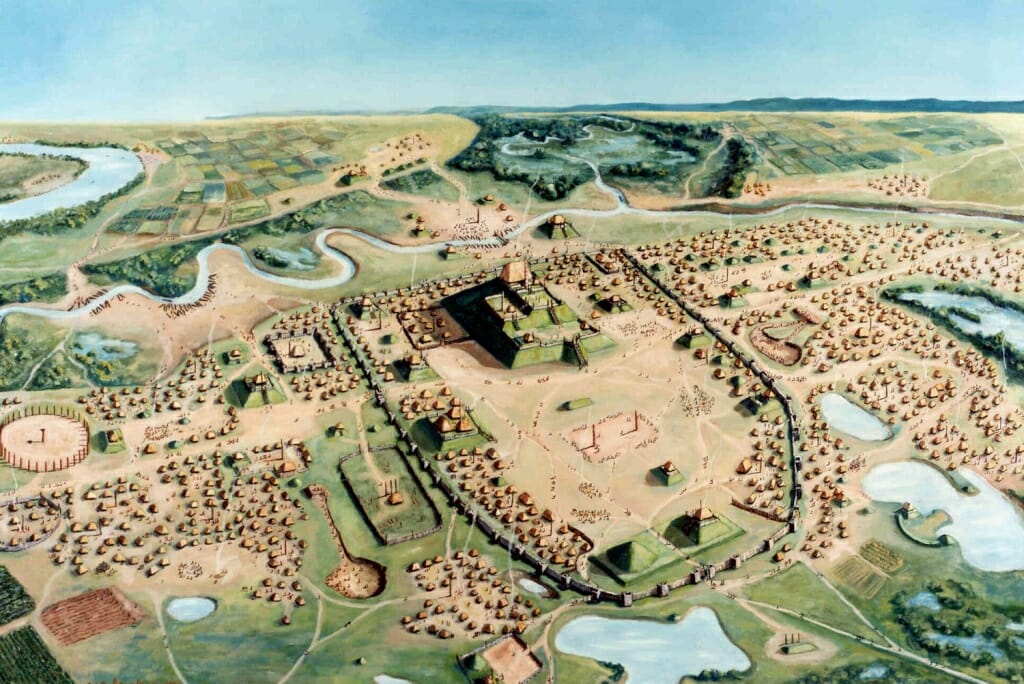

For example, in 2015, co-author Samuel Munoz, a former UW-Madison graduate student and now a professor at Northeastern University, was the first to collect one of the Horseshoe Lake sediment cores, which White had used in his study. the nearby Mississippi River was significantly flooded at approximately 11:50 am

White's latest study combines archaeological and environmental evidence.

"When we use this method, we can make comparisons with environmental conditions that we have not been able to do yet," says White, now a PhD student at UC Berkeley.

Using the Munoz core and another White collected on Horseshoe Lake, the research team measured the relative amount of faecal stanols from human beings in the sediment layers. They compared these levels with stanol levels known to come from bacteria in the soil to establish a baseline concentration for each layer.

They examined the cores of lakes in search of floods and also looked for climate indicators to know if the weather conditions were relatively wet or dry. These indicators, the ratio of a heavy form of oxygen to a light form, can show changes in evaporation and precipitation. Stevens explains that when the water evaporates, the light form of oxygen goes with it, concentrating the heavy form.

A model map of Cahokia and present St. Louis after the 1844 Mississippi Historic Flood. Courtesy of Samuel Munoz

The center of the lake showed that summer precipitation probably decreased towards the beginning of the Cahokia decline. This could have affected people's ability to grow their staple crops, maize.

Around 1150 archaeological records began to change in many ways, including the number and density of houses and the nature of artisanal production.

These are all indicators of "socio-political or economic stressors that stimulated a reorganization," she said. "When we see correlations with the climate, some archaeologists do not think climate is a factor, but it's hard to maintain this argument when evidence of significant climate change shows that people are facing new challenges. "

This is resonating today, she adds.

"Crops can be very resilient to climate change, but resilience does not necessarily mean there is no change. There may be a cultural reorganization or the decision to move or migrate, "says Schroeder. "We can see similar pressures today but fewer options to move."

For White, the study highlights the nuances and complications common to so many cultures and shows how environmental changes can contribute to the social changes already at stake.

The study was funded by the Geological Society of America and California State University, Long Beach.

[ad_2]

Source link

Share via Facebook

Share via Twitter

Share via Linked In

Share by e-mail