[ad_1]

Without the ice cap, sunlight would have warmed the ground enough for tundra vegetation to cover the landscape. Oceans around the world would have been more than 10 feet taller, and possibly even 20 feet taller. The land on which Boston, London and Shanghai now stand would have been under the waves of the ocean.

All of this happened before humans started to warm the Earth’s climate. The atmosphere then contained much less carbon dioxide than it does today, and it was not rising as quickly. The ice core and the ground below is sort of a Rosetta Stone for understanding how durable the Greenland ice sheet has been during past warm periods – and how quickly it could melt again when the climate warms. .

Danish secret military bases and freezers

The story of the Ice Core begins during the Cold War with a military mission called Project Iceworm. Beginning in 1959, the U.S. military transported hundreds of soldiers, heavy equipment, and even a nuclear reactor through the northwestern Greenland ice sheet and dug a base of tunnels inside the ice cream. They called it Camp Century.

It was part of a secret plan to hide nuclear weapons from the Soviets. It was known to the public as an arctic research laboratory. Walter Cronkite even visited and filed a report.

Camp Century didn’t last long. Snow and ice slowly began to crush the buildings inside the tunnels below, forcing the military to abandon it in 1966. During its short life, however, scientists were able to extract the core from ice and start analyzing the history of Greenland’s climate. As the ice accumulates from year to year, it picks up layers of volcanic ash and changes in precipitation over time, and it traps air bubbles that reveal the past composition of the ice. atmosphere.

One of the original scientists, glaciologist Chester Langway, kept the samples of frozen carrots and soil at the University of Buffalo for years, then shipped them to a Danish archive in the 1990s, where the soil became quickly been forgotten.

A few years ago our Danish colleagues found the soil samples in a box of glass cookie jars with faded labels: “Camp Century Sub-Ice”.

A surprise under the microscope

On a hot day in July 2019, two soil samples arrived at our laboratory at the University of Vermont, frozen solid. We started the painstaking process of splitting up the precious few ounces of frozen mud and sand for different analyzes.

First, we photographed the stratification in the ground before it was lost forever. Then we chiseled out small pieces to examine them under a microscope. We melted the rest and saved the old water.

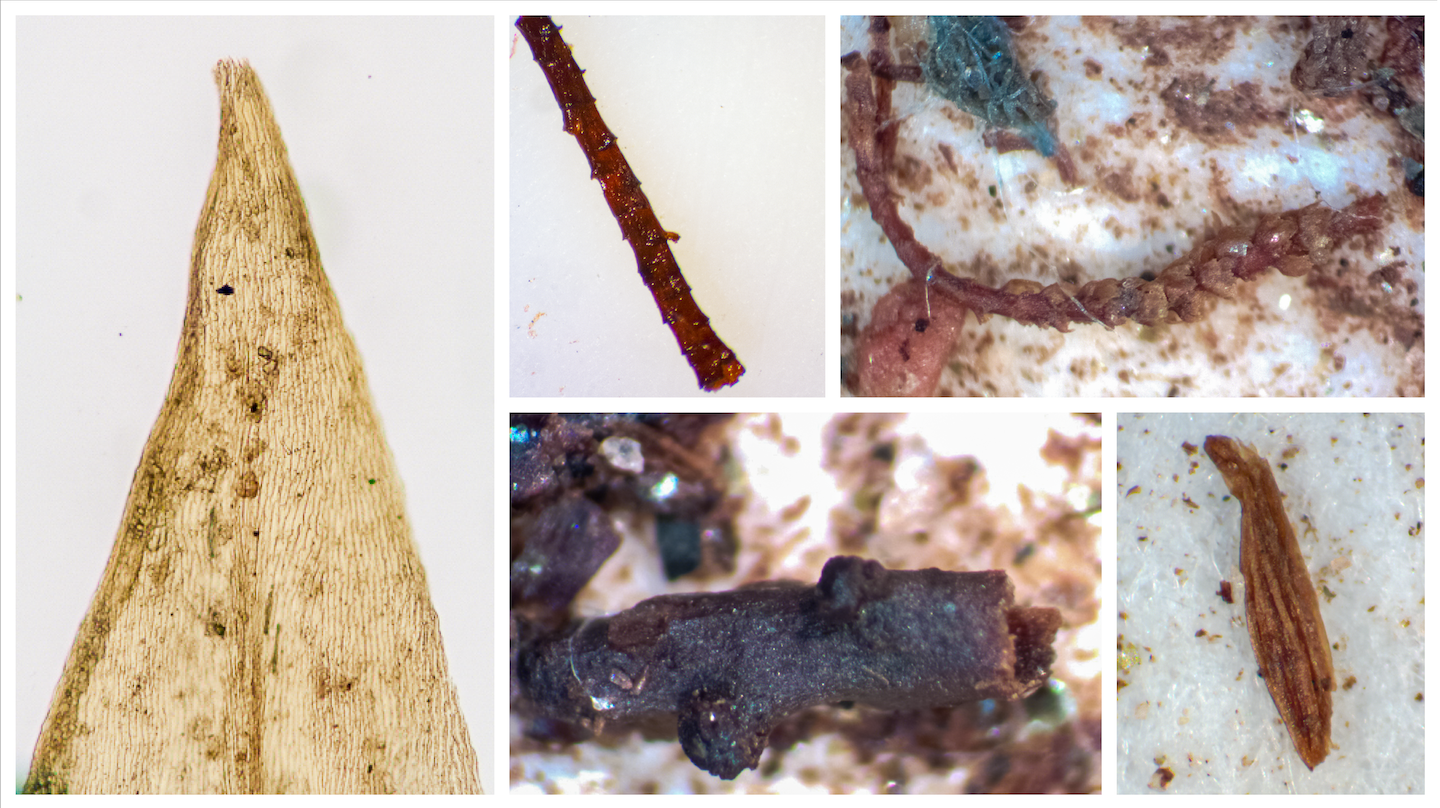

Then came the biggest surprise. While we were mopping the floor, we spotted something floating in the rinse water. Paul grabbed an eyedropper and filter paper, Drew grabbed tweezers and turned on the microscope. We were absolutely amazed looking at the eyepiece.

We looked back at leaves, twigs and mosses. It wasn’t just dirt. It was an ancient ecosystem perfectly preserved in the natural frost of Greenland.

Meet the million-year-old moss

How old were these plants?

Over the past million years, the Earth’s climate has been punctuated by relatively short warm periods, usually lasting around 10,000 years, called interglacials, when there was less ice at the poles and the sea level was higher. The Greenland ice sheet has survived all of human history during the Holocene, the current interglacial period of the past 12,000 years, and most of the interglacials in the last million years.

But our research shows that at least one of these interglacial periods was warm enough for a period long enough to melt large portions of the Greenland ice sheet, allowing a tundra ecosystem to emerge in northwest Greenland. .

We used two techniques to determine the age of the soil and plants. First, we used cleanroom chemistry and a particle accelerator to count the atoms that form in rocks and sediments when exposed to natural radiation that bombards Earth. Next, a colleague used an ultra-sensitive method to measure the light emitted by the grains of sand to determine the last time they were exposed to the sun.

The one million year delay is important. Previous work on another ice core, GISP2, mined from central Greenland in the 1990s, showed that ice was also absent there for the last million years, possibly around 400,000 years ago. .

Lessons for a world facing rapid climate change

The loss of the Greenland ice cap would be catastrophic for humanity today. The melted ice would raise the sea level by more than 20 feet. It would reshape the coasts of the whole world.

About 40% of the world’s population lives within 60 miles of a coast and 600 million people live within 30 feet of sea level. Antarctica will pour more water into the oceans. Communities will be forced to relocate, climate refugees will become more common and expensive infrastructure will be abandoned. Already, rising sea levels have amplified flooding from coastal storms, causing hundreds of billions of dollars in damage each year.

The story of Camp Century covers two critical moments in modern history. An arctic military base built in response to the existential threat of nuclear war has inadvertently led us to discover another threat from ice cores – the threat of sea level rise due to man-made climate change . Today, his legacy helps scientists understand how the Earth responds to a changing climate.

[Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter.]

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit news site dedicated to sharing ideas from academic experts. It was written by: Andrew Christ, University of Vermont and Paul Bierman, University of Vermont.

Read more:

Andrew Christ receives funding from the Gund Institute for Environment and the National Science Foundation.

Paul Bierman receives funding from the US National Science Foundation and the UVM Gund Institute for Environment.

[ad_2]

Source link