[ad_1]

Do-it-yourselfers know that if you put a grape cut in half in a microwave oven with just a little bit of skin connecting it, you will get sparks and a plume of ionized gas called plasma. Thousands of YouTube videos documenting the effect. But the standard explanation provided to explain why this is happening is not entirely accurate, according to a new paper published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. And its authors only needed to destroy a dozen microwaves to prove it.

"Many microwaves were actually injured during the experiments," acknowledged co-author Hamza Khattak of Trent University in Canada. "At one point, we had a microwave graveyard in the lab before we got rid of the first many iterations in electronic waste."

The co-author, Aaron Slepkov, became interested in the phenomenon for the first time when, in 1995, while an undergraduate student, he had no formal explanation (ie scientifically rigorous and revised by peers) of how the plasma was generated. After completing his PhD and establishing his own research group at Trent University, he began making his own experiments (microwave grapes for science) with one of his undergraduate students . They used thermal imaging and computer simulations of grapes and hydrogel beads in their experiments.

In order to capture the process in front of the camera, some microwave modifications were necessary, such as drilling holes and removing the door, so that you could better look inside while the machine was active (opening was carefully covered with a net to prevent leaks). And of course, the experiment itself can be dangerous for microwaves: running the almost empty oven produces a ton of unabsorbed harmful radiation. That's why the group worked in 12 microwaves during the study.

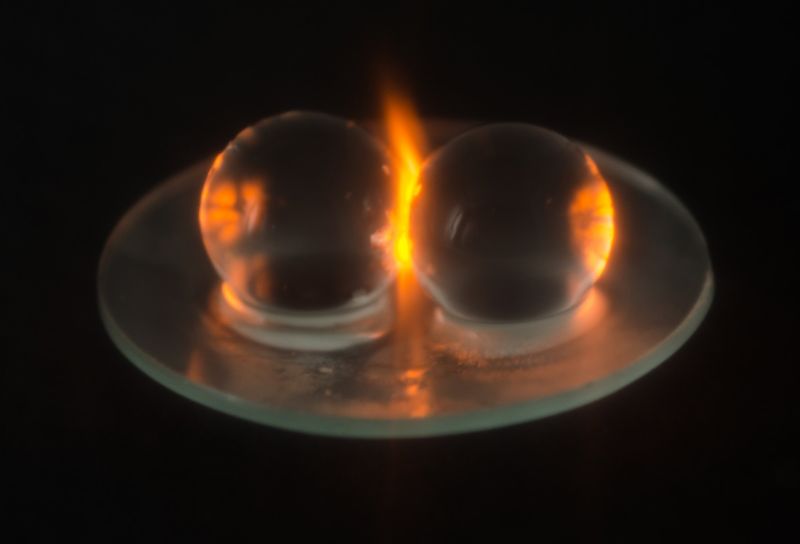

The micro-baking of the two halves of a grape produces sparks, and then a plume of fiery plasma.

H.K. Khattak et al.

The usual explanation for the generation of plasmas is that the grapes are so small that the radiating microwaves concentrate heavily in the grape tissue, tearing certain molecules to generate charged ions (adding to the electrolytes already present in the grapes). The electromagnetic field that forms causes the ions to pass from one half of grape to the other via the skin that connects them, at least initially. It is at this point that you get the initial sparks. Eventually, the ions also begin to cross the ambient air, ionizing it to produce this hot plasma plume.

"The previous explanations rested on the idea that the grape was acting as an antenna and that an electric current was being generated through the" bridge of the skin "holding the two halves of a grape together", said co-author Pablo Bianucci of Concordia University in Montreal, who did the computer simulations for the study. This is the current conventional wisdom that generates plasma.

These new experiences show that it is not quite correct. The skin bridge is not necessary for the effect to occur.

On the contrary, "our interpretation is that the plasma is generated by an electromagnetic" hot spot "which is a purely (microwave) volume effect," Bianucci said. "Grapes have the right refractive index and the right size to" trap "microwaves, and the proximity of two of them leads to the creation of that hot spot between them."

Once this hot spot is created, the powerful electromagnetic fields at this point transfer the energy to the grape ions. Here! A plasma of fire.

Trent scientists have discovered that the trick also works with gooseberries, large blackberries and quail eggs, as well as hydrogel beads – plastic beads soaked in water. water. Virtually anything that is the size of a grape will work because it is the ideal size to best amplify the microwaves to produce this hot spot at intense concentration.

DO I: PNAS, 2019. 10.1073 / pnas.1818350116 (About DOIs).

[ad_2]

Source link