[ad_1]

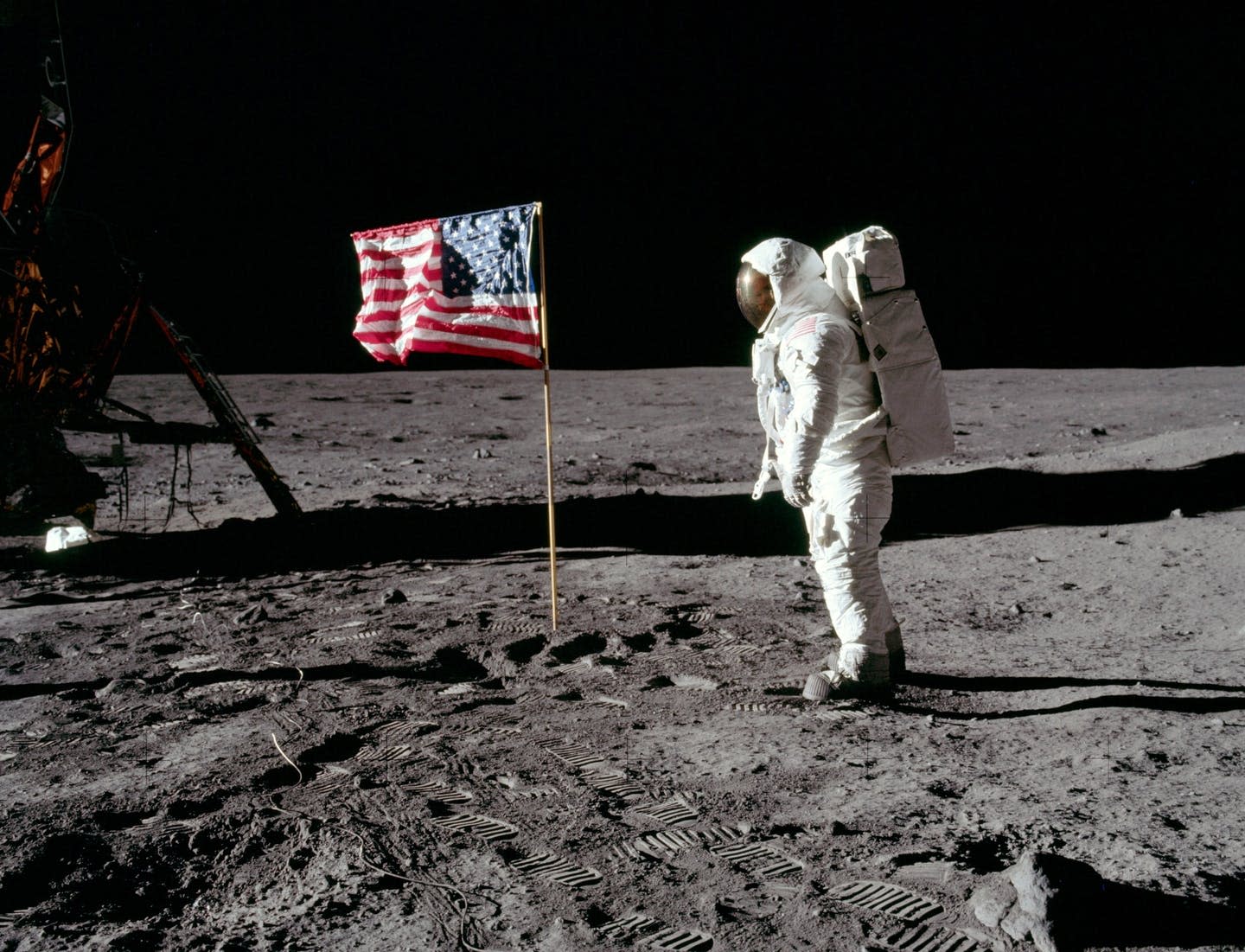

It’s hard to worry about the boot prints stuck in the ground 238,900 miles away, as humanity suffers from the combined burden of a ruthless virus and political unrest. But how humans deal with those bootprints and the historic lunar landing sites they are found on will say a lot about who we are and who we seek to become.

On December 31, the law “A small step to protect human heritage in space” came into force. As far as the laws are concerned, it is quite benign. It is forcing companies that work with the National Aeronautics and Space Administration on lunar missions to agree to be bound by otherwise unenforceable guidelines intended to protect US landing sites on the moon. It’s a fairly small group of affected entities. However, it is also the first law enacted by a nation that recognizes the existence of human heritage in outer space. This is important because it reaffirms our human commitment to protect our history – as we do on Earth with sites like the Historic Sanctuary of Machu Picchu, which is protected by instruments like the World Heritage Convention – while recognizing that the he human species thrives in space. .

I am an attorney who focuses on space issues that aim to ensure the peaceful and sustainable exploration and use of space. I believe that people can achieve world peace through space. For this to happen, we must recognize the landing sites on the Moon and other celestial bodies as the universal human achievements that they are, built on the research and dreams of scientists and engineers spanning centuries on this globe. . I believe the One Small Step Act, enacted in a conflicting political environment, demonstrates that space and preservation are truly non-partisan, even unifying, principles.

The moon quickly gets crowded

It is only a matter of decades, maybe just years, before we see a continued human presence on the Moon.

While it would be good to think that a human community on the Moon would be a collaborative, multinational utopia – albeit situated in what Buzz Aldrin has described as “magnificent desolation” – the point is that people are rushing for it again. reach our lunar neighbor.

The US project Artemis, which includes a goal of sending the first woman to the moon in 2024, is the most ambitious mission. Russia has reinvigorated its Luna program, paving the way to put cosmonauts on the moon in the 2030s. However, in a race once reserved for superpowers, there are now several nations and several private companies with a stake.

India plans to send a rover to the moon this year. China, which implemented the first successful lunar return mission since 1976 in December, has announced multiple lunar landings in the coming years, with Chinese media reporting plans for a crewed mission to the moon during the decade. South Korea and Japan are also building landers and lunar probes.

Private companies like Astrobotic, Masten Space Systems, and Intuitive Machines work to support NASA missions. Other companies, like ispace, Blue Moon and SpaceX, while also supporting NASA missions, are preparing to offer private missions, especially for tourism. How will these different entities work around each other?

Space is not without law. The 1967 Outer Space Treaty, now ratified by 110 nations, including all current space countries, offers guiding principles that support the concept of space as a province of all mankind. The treaty explicitly states that all countries and, by implication, their nationals have the freedom to explore and free access to all areas of the moon.

It is true. Everyone has the freedom to roam wherever they want – on Neil Armstrong’s footprint, near sensitive science experiments, or to a mining operation. There is no concept of ownership on the Moon. The only restriction on this freedom is the admonition, found in Article IX of the treaty, that all activities on the Moon must be carried out “with due regard for the corresponding interests” of all others and requiring that you consult the others if you could cause “harmful interference”.

What does it mean? From a legal point of view, no one knows.

Outstanding Universal Value

It can reasonably be argued that interfering with a lunar mining experiment or operation would be detrimental, cause quantifiable damage, and thus violate the treaty.

But what about an abandoned spacecraft, like the Eagle, the Apollo 11 lunar lander? Do we really want to trust “due respect” to prevent the intentional or inadvertent destruction of this inspiring piece of history? This object commemorates the work of the hundreds of thousands of individuals who worked to put a human on the Moon, the astronauts and cosmonauts who gave their lives in this quest to reach the stars, and the silent heroes, like Katherine Johnson, who fueled the math that made it.

The lunar landing sites – from Luna 2, the first man-made object to strike the moon, to each of the crewed Apollo missions, to Chang-e 4, which deployed the first rover to the other side of the Moon – testify in particular to humanity’s greatest technological achievement to date. They symbolize all that we have accomplished as a species and hold such promise for the future.

[Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter.]

The One Small Step Act is aptly named. It’s a small step. It only applies to companies that work with NASA; it only concerns US lunar landing sites; it implements obsolete and untested recommendations to protect historic lunar sites implemented by NASA in 2011. However, it offers significant advances. It is the first legislation in a country to recognize an above-ground site as having “outstanding universal value” for humanity, language taken from the World Heritage Convention which has been unanimously ratified.

The law also encourages the development of best practices for protecting human heritage in space by evolving concepts of respect and harmful interference – an evolution that will also guide the way nations and businesses work together. Small as it may be, the recognition and protection of historic sites is the first step towards developing a model of peaceful, sustainable and effective lunar governance.

Boot prints are not yet protected. There is a long way to go towards a binding multilateral / universal agreement to manage the protection, preservation or commemoration of all human heritage in space, but the One Small Step Act should give us all hope for the future in space and here on Earth.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit news site dedicated to sharing ideas from academic experts. It was written by: Michelle LD Hanlon, University of Mississippi.

Read more:

Michelle LD Hanlon is affiliated with For All Moonkind, a 501 (c) (3) nonprofit that seeks to protect each of the six human lunar landings and similar sites in space as part of our common human heritage.

[ad_2]

Source link