[ad_1]

Multimedia playback is not supported on your device

The BBC World Service is launching Monday a series of special podcasts to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the landing of Apollo 11 Moon. Called 13 Minutes To The Moon, it details the final phase of the descent on the lunar surface – as well as the months and years that led to those extraordinary moments when the world held its breath. Presenter Kevin Fong remembers meeting the unique characters who contributed to the podcasts, including some of the last remaining Apollo astronauts.

When we created 13 Minutes To The Moon, we spent most of the four weeks traveling the United States looking for people who, one day in 1969, had managed to put a man in security on the surface of another world.

In Texas, we found Charlie Duke, a lunar module pilot on Apollo 16, and Walt Cunningham, a control module pilot on the first Apollo 7 test flight.

In Chicago, we interviewed the legendary Jim Lovell, who orbited the moon in 1968 during the daring flight of Apollo 8, and who of course later commissioned the unfortunate Apollo 13.

The very first of our interviews for the series was with Michael Collins who, along with Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin, finished the Apollo 11 crew as part of the mission that saw humans landing on the Moon for the very first time in the summer of 1969..

I remember arriving at a cheap hotel somewhere west of the Florida Everglades the night before and standing in the parking lot staring into the night sky at the rising moon, knowing that the next day I would talk to someone else. One who had stolen once there.

But astronauts were only the most visible part of a gigantic iceberg.

Copyright of the image

NASA

Buzz Aldrin salutes the American flag: the Moonwalkers were the tip of a very long spear

In total, no less than 400,000 people participated in the Apollo project. Almost all of them felt deeply connected to the mission, and although only a few people eventually flew to the moon, the workers, engineers, technicians and scientists working under the Apollo program felt that on July 20, 1969, part of the Between them also landed on the moon.

So we wanted to tell all these stories, framed by the drama of the last 13 minutes of descent before the touchdown on the lunar surface.

This period of the mission was marked by crises and, as Armstrong will testify thereafter, by "endemic of unknowns".

As Armstrong and Aldrin descended 50,000 feet above the moon, radio communications with the Earth were interrupted. the lunar module ran for a long time on its target landing site; the onboard computer – on which astronauts absolutely depended – began to display error codes that the team had never seen before; and in the last seconds, it seemed that Armstrong and Aldrin could actually run out of fuel.

In the audio recordings of the mission control of the past 13 minutes, you can hear the tension in each spoken word, phrase and silence. So the series producer, Andrew Luck-Baker, and I set out to dispel those difficult moments and explain how the frantic race to get a crew to the surface of the moon – before the end of the decade – conspired to create this exhilarating finale. moments.

Growing up in the 1970s, as a result of Project Apollo, I devoured everything I could find that told these stories: every TV show, every book, every magazine.

Later, it led me to pursue a scientific career in science.

I studied astrophysics and then medicine at University College London, and then I had the chance to work with NASA's Johnson Space Center as a physician and visiting researcher.

This life and the adventures that accompanied it were led largely by the people who went to the moon.

Copyright of the image

NASA

The Apollo Effect: This success has inspired countless millions of people around the world.

Even as a schoolboy, I think I understood that if people could fire human beings from the surface of our planet and land them in another world, then everything must be possible – no matter what – at all.

And so, when the opportunity to do this podcast series came up, I jumped on the opportunity.

We interviewed dozens of people from all over the United States and, although it was something really worth spending time sitting in the astronaut lounge that had been flying and walking on the moon, it was our interview of the former Stephen Bales flight controller for me, the head and shoulders were above everything else.

I like to think of Steve as Luke Skywalker of the Apollo program.

Copyright of the image

NASA

Steve Bales: Like many of his colleagues, the man from Iowa was under 30 years old.

He grew up in an Iowa farming community, but on a clear day he would go out, look into a dark, star-filled sky and dream of space adventure.

Later, with an engineering degree, he left the Iowa countryside to travel to the hustle and bustle of the city of Houston.

He started as an intern at Johnson. A little more than a mere clerk, he offered visiting VIPs mission control visits. But he waived these obligations whenever he could to talk to the flight controllers about their job of operating the spacecraft systems and their human occupants, flying over the space well above them. # 39; them.

He decided that was where he wanted to be, to be part of the team leading the missions. And with time, his youthful enthusiasm has won.

When President John F. Kennedy set his country on the path to the moon to come in a decade, NASA had to muster a workforce capable of keeping that promise. They hired quickly and often without maintenance, choosing instead to recruit people with the required skills and then evaluate them at the workstation.

The flight controllers in mission control were incredibly young: for the Apollo project, they were on average only 26 years old. And while it seems odd that such a responsibility lies with a group of innovative employees who do not leave the university, their youth has generally been considered an important asset.

"It's not that they did not understand the risks," said Gerry Griffin, director of Apollo Flying, "they had everything." just not afraid. "

Copyright of the image

NASA

Without fear and ready to devote themselves entirely to the task, they were exactly what the space program needed.

Steve quickly rose through the ranks, rising from a technician position to support missions from the back office to a mission controller position as a flight controller for the Gemini project. . At that time, he was only 23 years old.

In the control of the mission, someone was constantly monitoring, even if you did not know who and how, while the attention was turning from orbital flights of Gemini to Project Apollo's activity and landing on the moon, Steve was assigned to the guidance, navigation and control team. . These were the people responsible for the orientation of the spacecraft while it was flying in space.

In the grueling simulations of the months before July 20, 1969, Steve continued to impress. As the mission leaders began gathering the team of flight controllers to witness Apollo 11's first historic attempt to land on the moon, Steve, now 26, found himself in the air. .

For landing, he would occupy his position as an orientation officer, one of the most important roles of mission control. And the enormity of this task did not escape him.

"Here's a 26-year-old kid," he said, disbelief even after 50 years, "a kid who can stop a space mission!"

Copyright of the image

NASA

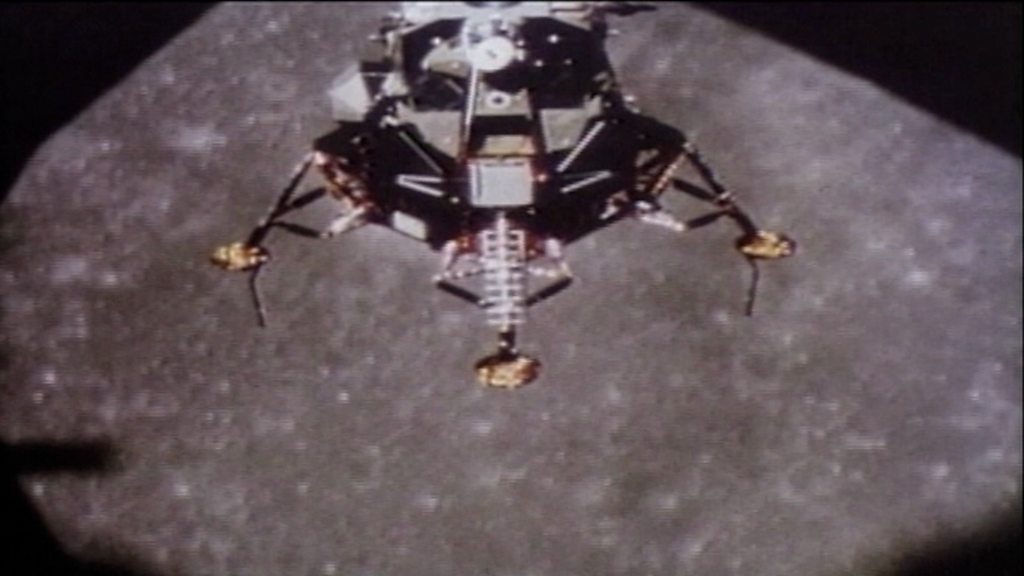

Inside the lunar module "Eagle", Armstrong and Aldrin were seeing unknown computer codes

In the middle of the descent of Armstrong and Aldrin over the last 13 minutes, the crew and its essential support team at Mission Control have been facing problem by issue.

They were crossing the lunar surface too quickly and were likely to overtake their intended landing site.

Their radio communications with the Earth became uneven, and then, while still closer to the surface, their on-board computer triggered a series of alarms that the crew had never seen before, alarms that they did not understand.

For landing on the moon, the crew relied almost entirely on its onboard autopilot, the Apollo Guidance Computer. And although today we like to joke about the fact that the processing power of this computer was limited, at the time, it was by far the most complex and the most sophisticated aboard the spaceship. His ability to assist astronauts in this almost impossible feat was absolutely essential to the success of the mission.

The onboard screen and keyboard looked like a giant calculator and its rudimentary display was only able to flash a series of numbers to display information and help identify problems.

On the audio of the mission, recorded from the booth, you can hear Buzz Aldrin, then Neil Armstrong recite the string of numbers that appears on the screen: 1202, that they read in the emptiness as follows: "Twelve-oh-two".

In mission control, no one understood what was happening. Was the computer on the verge of breaking down? Would they have to give up the landing? Was Armstrong and Aldrin's life in danger?

There was a pause of a few seconds while the team struggled to find an answer. It was at this point that Neil Armstrong, normally frozen, found himself again in the radio transmission, almost swinging the words: "Give me a reading of the twelve-oh-two."

Copyright of the image

NASA

Neil Armstrong: Calm down in the most stressful situations

This is the only time a person we spoke to remembers hearing an emergency note in the voice of the astronaut.

In the 15 seconds that elapsed between Armstrong and Aldrin who detected the alarm for the first time, Steve Bales spoke with his support team behind the scenes, desperately searching for an answer to the question urgent from Armstrong.

The seconds passed, the lunar module continuing to fall towards the moon and the crew still not knowing if its vital onboard computer was still able to guide them through the landing.

It was the essence of mission control. Apollo flights have caused problems with complex systems that have appeared in real time and have to be solved by human operators at the moment. And while Armstrong was waiting, all eyes turned to Steve Bales, the boy from Iowa.

Behind the scenes, Steve's colleague, Jack Garman, acknowledged that the 1202 code was similar to something they had seen during a simulation several weeks earlier.

He told them that the computer was struggling but still working and was able to accomplish its critical tasks.

On this occasion, when the alarm was triggered during the dress rehearsal, Steve had interrupted the mission unnecessarily and had been urged to do so.

So, when the 1202 alarm was triggered in the final minutes of the Apollo 11 descent, Steve Bales quickly responded, "We are going to take this flight." And the rest of the course is history.

Copyright of the image

NASA

We talked to Steve Bales' flight controllers and directors. They painted the portrait of an irrepressible young man, brimming with enthusiasm but nevertheless very competent and absolutely reliable.

Having grown up dreaming of stars that night in the summer of 1969, he found himself in one way or another at the heart of one of the most difficult and critical decisions. of the whole Apollo program and gave a judgment to the second who saved the mission.

After, when the crew was safe on the surface, flight director Gene Kranz brought him to join him at a frantic press conference. And when his mission control was finally over, he made his way through the long corridors that led from the Mission Operations Control Room to the bright sun of Houston.

His eyes blue, he remained motionless, blinking. The boy from Iowa who had helped put a human being on the moon.

Multimedia playback is not supported on your device

Our journey through America in search of people and stories that together made up the essence of the Apollo program was a pure work of love.

Wherever we shot, there were stories like Steve's, with the safety and success of the mission perpetually in the balance.

Someone once said Neil Armstrong that he was one of the few characters of the 20th century to have a chance to remember the 30th century. But Armstrong was only the tip of the spear, and our series of podcasts offers us an opportunity to celebrate not only him and his fellow astronauts, but also the truly remarkable army of people without whom we would never have set foot on the moon.

The first episode of 13 Minutes To The Moon will be available for download on May 13, and new episodes will be released every Monday, to culminate in the latest edition on July 20, the anniversary date of the Apollo landing. 11. Podcasts can be downloaded from the BBC and the world's leading platforms.

[ad_2]

Source link