[ad_1]

By

Neuroscientists provide striking results that suggest that children's brains may not be as fluid as expected.

Using state-of-the-art brain imaging techniques, Vaidehi Natu of Stanford University in California, as well as his colleagues at the Max Planck Institute for Cognitive and Physiological Sciences. Human brain cells in Leipzig, Germany, provide striking results that suggest that children's brains do not dilute as much as expected. There seems to be an increase in myelin, which is the fatty sheath insulating nerve fibers.

Looking back a little, studies have repeatedly shown that some areas of the cerebral cortex (the outermost layer of the brain) become thinner as children develop. And just 3 mm thick, on average, studies have revealed that children can apparently lose around 1 mm of gray matter in adulthood. Various hypotheses have been put forward to explain these huge losses. For example, it is established that gray matter cells and their connections can be naturally "pruned", presumably to promote a more efficient brain. So, perhaps the extensive size in young brains could explain the thinning. Alternatively, we know that our brains develop during development. Maybe the cortex is stretched in the process? The new research certainly does not exclude these processes, and actually finds evidence for them. However, new work suggests that a significant change has not been detected, due to the limitations of previous measurements.

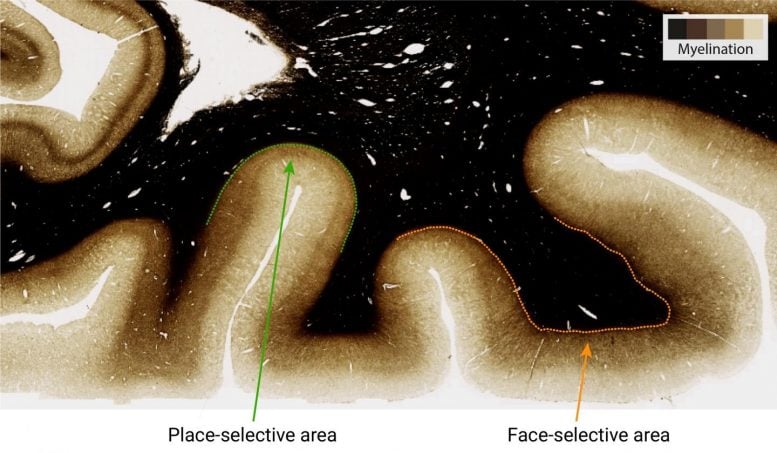

Higher myelination (darker staining) is found in the selective zone of the upper visual cortex, compared to the selective zone of the site. Credit: MPI CBS

More specifically, the present study shows that when measured with quantitative MRI (or qMRI), it appears that younger brains are becoming more myelinated. This is a good thing, but it can disturb estimates of cortical thickness (gray matter). Myelin is the "white" in the white matter. It is a fatty sheath that isolates many nerve fibers and allows faster neurotransmission. The problem is that measurements of the gray matter thickness depend essentially on the detection of the boundary between the white matter and the gray matter. As Natu and Kirilina have discovered, this limit can be obscured and the cortical thickness underestimated if myelination increases during development. The researchers obtained these results by examining adults and children using advanced quantitative MRI techniques.

Evgeniya Kirilina, who works in the Department of Neurophysics of CBS MPI, calls for caution. "The fact that the cortex becomes fluid during development is well established, even with histological methods. We do not claim that thinning does not occur. But estimates may be wrong in some cases because of simultaneous myelination. "

The team was actually looking at three specialized brain areas in the upper visual cortex. Despite their proximity, each showed a unique development model, highlighting the need for a cautious interpretation. The facial and verbal recognition areas showed the myelination effect described above, while the area recognition area showed apparent thinning but no indication of myelination. Instead, it seemed to change structurally, stretching in time. Highlighting the important link between structure and function, the differences in myelination of these functionally specialized regions have been confirmed in the post mortem brains of adults, using both ultra-high field MRI and histology. .

The implications of these new discoveries are quite broad. Decades of work will need to be reviewed and evaluated for precision. For example, abundant literature suggests that the thickness of the cortex changes when acquiring new skills. It will now be necessary to determine whether myelination also plays a role. In addition, myelin degradation can lead to debilitating diseases. This is exactly what is happening in multiple sclerosis. More accurate measurement techniques such as the QMRI promise to improve the detection, monitoring and treatment of such conditions.

Reference: "The apparent thinning of the human visual cortex during childhood is associated with myelination" by Vaidehi S. Natu, Jesse Gomez, Michael Barnett, Brianna Jeska, Kirilina Evgeniya, Carsten Jaeger, Zonglei Zhen, Siobhan Cox, Kevin S. Weiner and Nikolaus Weisk and Kalanit Grill-Spector, September 23, 2019, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

DOI: 10.1073 / pnas.1904931116

[ad_2]

Source link