[ad_1]

There was a time when the idea of an international space station would only have been seen as a fantasy. After all, the human spaceflight programs of the United States and the Soviet Union were started largely as a Cold War race to see which country would be the first to arm low earth orbit and secure what. military strategists believed to be the pinnacle. These early rockets, not so far removed from intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs), were fueled as much by competition as by kerosene and liquid oxygen.

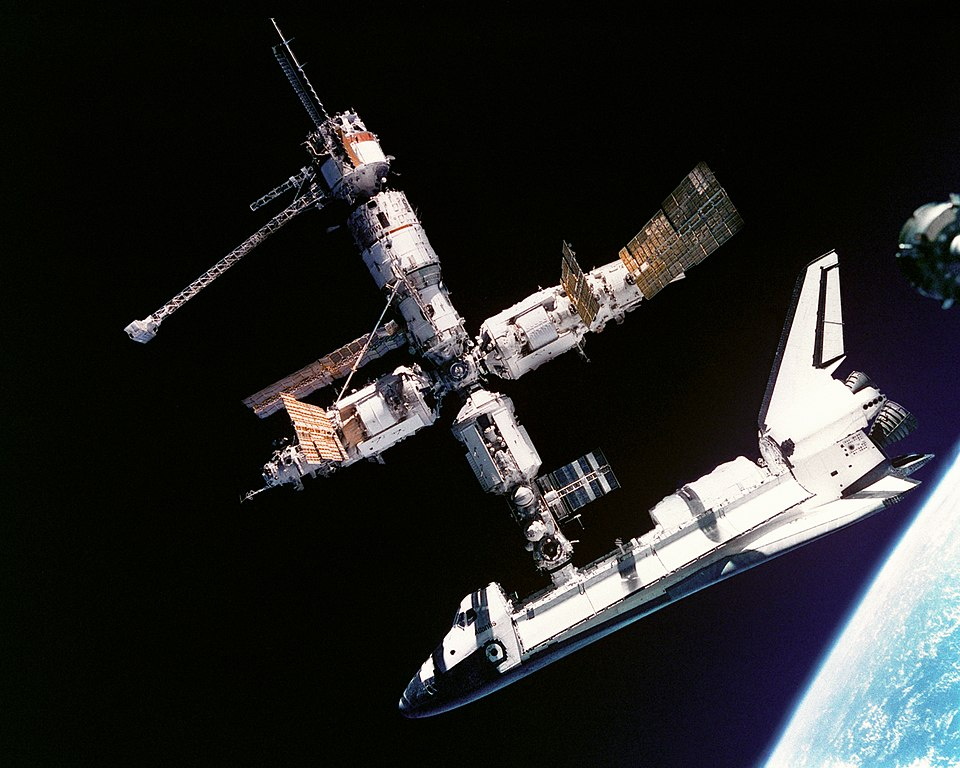

Fortunately, cooler heads prevailed. The soviet do not understand space stations may have carried a 23mm cannon adapted from the rear cannon of the Tu-22 bomber to repel any American vehicle that came too close, but the weapon was never fired in anger. Eventually, the two countries even saw the benefit of working together. In 1975, a joint mission saw the last Apollo capsule dock with a Soyuz using a special adapter designed to compensate for the different docking hardware used on the two spacecraft.

Relations improved further after the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, with the US space shuttle making nine trips to Russia Me space station between 1995 and 1997. A new era of cooperation had begun between the major countries of the space fairing world, and with the engineering lessons learned during the shuttle-Me program, engineers from both space agencies began to lay the foundation for what would become the International Space Station.

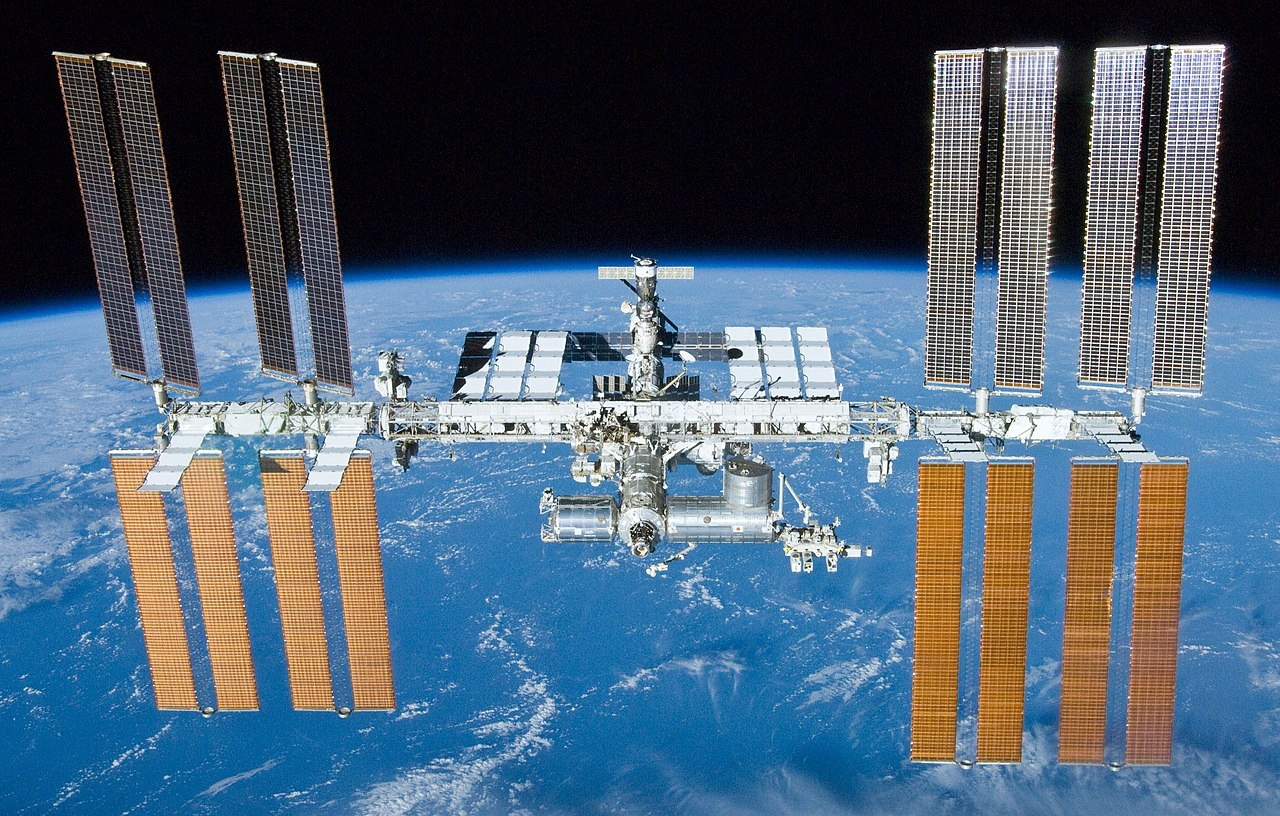

Unfortunately, after more than twenty years of continued occupation of the ISS by the United States and Russia, it seems that cracks are finally starting to form in this attempt at a scientific alliance. With accusations expected to be responsible for a series of serious incidents aboard the in-orbit lab, the prospects for future international collaboration in Earth orbit and beyond have not been so bad since the strongest. of the cold war.

The wild ride from the station

The most recent drama began with the docking of the highly anticipated Russian Science module on July 29. Although ultimately successful, the process was anything but smooth, resulting in an unexpected journey for the occupants of the Station.

After more than a decade of delays and reshuffles, the arrival of Science would have been a historic event even if things had gone as planned. With a length of 13 meters (43 feet) and a mass of 20,300 kg (44,800 lb), the new versatile module eclipses everything but the Zarya and Star segments that served as the core of the Station during initial construction. The new module was not only remarkable for its size. The space shuttle is no longer in service, Science had to fly to the ISS on its own and perform an autonomous docking; a radical change from the way the majority of the previous modules had been transported and installed.

Despite some early glitches, everything seemed to have gone according to plan, and Russian cosmonauts were preparing to open the hatches of the new module when it suddenly began to fire its thrusters on board. Preliminary inquiries have determined that Sciences the guidance computer mistakenly believed it was still in free flight mode, and for reasons still poorly understood, its automated systems attempted to move it away from the Station. But with the module firmly attached to the lowest docking port on the ISS, Sciences instead, the thrusters begin to rotate the entire complex around its center of mass.

The station guidance system noticed the offset from its intended position and attempted to compensate using the Control Moment Gyroscopes (CMGs). When this was not enough to stop the spin, the thrusters on the Star module and finally the docked Progress MS-17 refueling vehicle were ordered to fire against the direction of rotation. While early NASA estimates claimed the station had only rotated 45 ° from its intended stance, the agency has since admitted that the complex rotated 540 ° in about 45 minutes.

The turnover rate was low enough that the crew members apparently did not notice it until they were warned by mission control, but the tussle between the modules that was causing the very unusual maneuver was putting the structure out of control. the station under constraints, it had never been designed. for. The slow fall also made communications difficult, as the Station’s antennas were continually away from their intended alignment. Zebulon Scoville, the on-duty NASA flight director, made the decision to officially declare a “spacecraft emergency” and the docked SpaceX Crew Dragon was energized if crew members were ordered to. clear out.

As Scoville later explained in an interview with The New York Times, neither the crew on board the station nor the mission control in Huston had the real ability to command Science during the test. As the module had not been fully integrated into the Station’s systems, it could only be controlled from a Russian ground station, but none was within range. Ultimately, it is believed that the mod thrusters only stopped firing because they ran out of thrusters.

In a scathing article published by IEEE spectrumFormer NASA engineer James Oberg said the incident was a worrying sign the space agency was returning to the complacent mindset that doomed the shuttles Challenger and Colombia. Specifically, it puts the priority on the safety of the crews.

An explosive accusation

In an apparent effort to limit the damage, Russia’s TASS news agency issued a rebuttal of what it claimed was a systematic attempt by Western journalists to cast doubt on the country’s space program. With the support of an anonymous senior official within Roscosmos, author Mikhail Kotov attempted to debunk twelve criticisms he identified in the cover of publications as diverse as Ars Technica and The daily beast.

Many of the claims have to do with funding, or more specifically, the lack of it. But Kotov dismisses the idea that Roscosmos’ meager budget leads to shoddy engineering or limited innovation, in fact, he retorts that fiscal conservatism is one of the agency’s main strengths. The article also explains the country’s efforts to replace Soviet-era facilities, spaceships, and boosters.

The list of relatively timid quasi-official statements would likely have gone unnoticed for the most part without the inclusion of an exceptionally inflammatory and completely unfounded claim that the hole discovered in a Soyuz capsule during a 2018 investigation was not the one. product. of an assembly error for so long supposed, but of a deliberate act of sabotage by the American astronaut Serena Auñón-Chancellor. Quoting the anonymous official, Kotov says the first-time astronaut may have suffered an “acute psychological crisis” due to a blood clot in his neck, and could have damaged the Soyuz capsule in the body. aim to speed up the crew’s return to Earth.

In response to this unprecedented ad hominem attack on one of their astronauts, and potentially the unauthorized disclosure of a private medical issue she may have suffered in orbit, NASA has apparently been able to pull together only the answers. more lukewarm. Kathy Lueders, Head of the NASA Human Space Flight Program, took to Twitter to say the agency supports its astronauts and that they do not believe the allegations are credible. NASA Administrator Bill Nelson then retweeted Lueder’s post, but no official post was added to the agency’s public relations website.

When it comes to upholding the reputation of Auñón-Chancellor, a woman who has dedicated more than a decade of her life to the agency, it seems NASA thinks a 37-word tweet should suffice. It’s hard to see such a milquetoast response as anything other than the administration caring more about the political ramifications of Roscosmos’ final contradiction than the career of one of their astronauts.

A separation of paths

NASA and most of its international partners have pledged to support the International Space Station until 2028 or 2030, but Russia has been reluctant to commit to extending its engagement beyond 2024. No later than the 7th June, Roscosmos chief executive Dmitry Rogozin said Russia will end its involvement in the ISS program in 2025 if US sanctions against the country are not lifted by the White House. Earlier in the year, Roscosmos also cited concerns about the age of the ISS as one of the reasons they were planning to launch a nationally developed outpost known as the Orbital Service Station. Russian (ROSS) in a near polar orbit. Its proposed route above Earth would make ROSS an ideal platform for observing Russia and the Arctic, but puts it largely out of reach for launching spacecraft from Cape Canaveral.

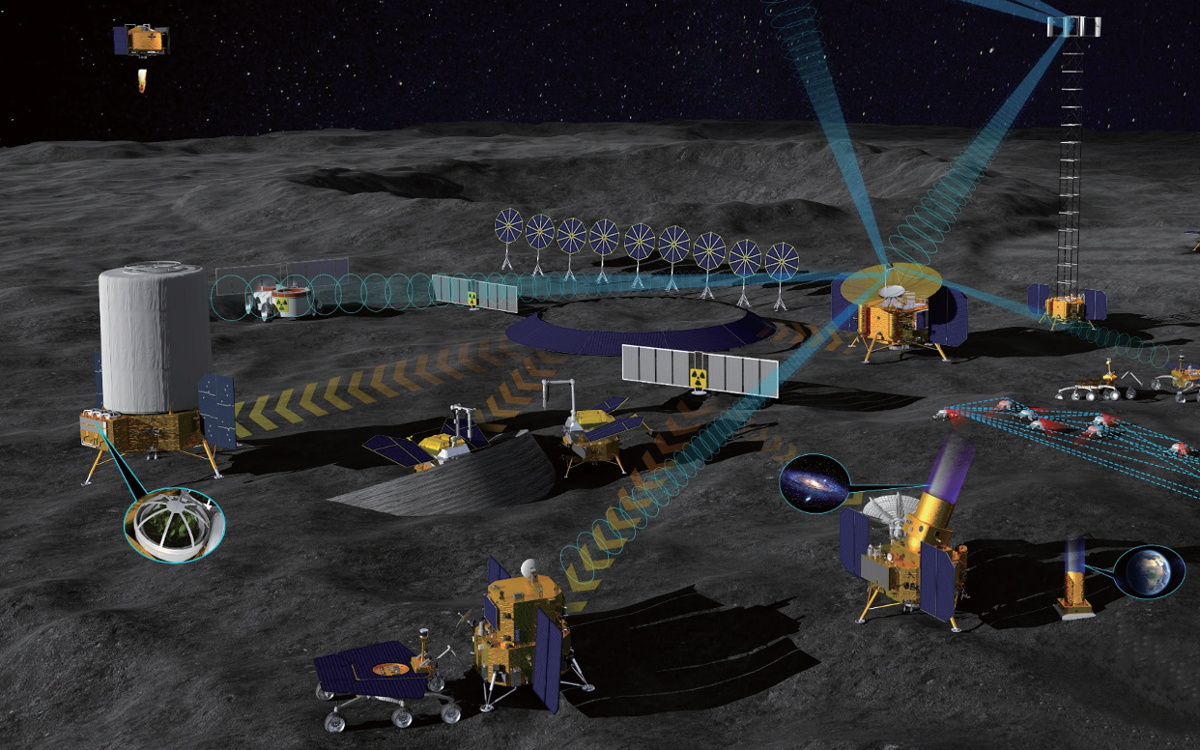

The growing divide between countries does not end in low earth orbit, either. Despite hopes that they would provide a module for NASA’s Lunar Gateway station, Russia is no longer among NASA’s international partners for the project. Instead, Roscosmos and the China National Space Administration (CNSA) have announced plans to build what they call the International Lunar Research Station (ILRS).

The robotic outpost would largely avoid human explorers in favor of highly mobile forward landers, telescopes, and rovers. Neither country has provided a firm timeline for the development and construction of ILRS, but it is not expected to become operational until the 2030s. Short-term human missions to ILRS, if they occur, would not start until 2040.

While Russia will almost certainly remain involved in the International Space Station program until ROSS is operational, it seems clear that the end of the country’s scientific alliance with the United States is on the horizon. While an improvement in White House-Kremlin relations over the next few years may see Roscosmos contributing to NASA’s Artemis lunar program to some extent, sharing spaceflight technology with China is a line in the sand that the United States is unlikely to cross.

[ad_2]

Source link