[ad_1]

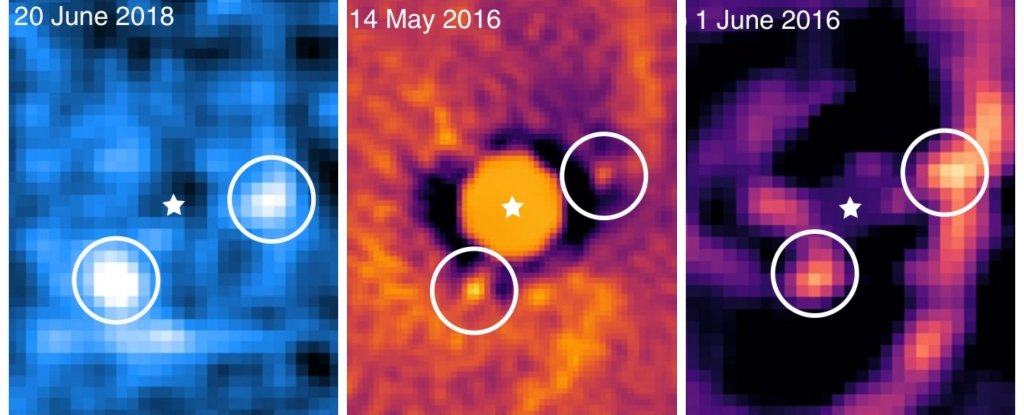

PDS 70, the star who gave us the first ever unconfirmed direct image of a planet being born, had an extra twist in its protoplanetary disk. In the follow-up observations, the astronomers found a second planet – and managed to take pictures of both.

This gives him the added honor of being the second multi-planet system to have been directly photographed unambiguously.

(The first was HR 8799, with its four exoplanets, one of which contains water in its atmosphere and the other, a stormy infernal world.)

The two planets orbiting the PDS 70 are the PDS 70b (the one that astronomers discovered last year) and the PDS 70c. The new image shows that they are digging a huge cavity in the protoplanetary disk of gas and dust that surrounds the young star, an orange dwarf only 370 light-years away from the screen.

It's a wonderful technical achievement and an incredible thing to see.

We know that there are many exoplanets. Thousands of people have been detected, mainly looking for the very slight attenuation that occurs when a planet passes a star or the slight flicker caused by the gravitational tug of the planet.

We also know that when the stars are newly formed, they are surrounded by a swirling disc composed of dust, rocks and gas. Planetary accretion is thought to occur when disk particles clash and stick to each other, becoming increasingly gravitational, collecting and cleaning the material from the orbital trajectory and eventually forming a planet.

Astronomers of the past have taken rather amazing pictures of these protoplanetary disks, with strong evidence of this orbital release.

But shooting a planet directly is much more difficult. Indeed, the exoplanets are generally very far away and are therefore too weak to be seen by our optical telescopes, especially when any light they can reflect is surpassed by the brightness of the star. And sometimes, what seems to be direct evidence is not what it seems.

So, although we can guess with certainty if there are baby planets in these discs, we have seen very little of them, which means there may be some not.

"With equipment like ALMA, Hubble, or ground-based adaptive optics-based ground-based telescopes, we see disks with rings and empty spaces.The open question is, are there planets? " said astronomer Julien Girard of the Institute of Space Telescope Sciences.

"In this case, the answer is yes."

Artistic illustration of the system (J. Olmsted / STScI)

Artistic illustration of the system (J. Olmsted / STScI)

The images obtained allowed scientists to infer quite a lot of information about the planets.

As we learned last year, the PDS 70b represents about 4 to 17 times the mass of Jupiter, gravitating around the star at a distance of about 20.6 per kilometer (3.22 billion kilometers) , a little further than Uranus in orbit around the Sun. . It takes about 120 years for a single orbit.

The planet was discovered with the help of the SPHERE planetary hunting instrument installed on ESO's very large telescope, with its coronagraphic filters blocking starlight and its polarizing filters that block specific wavelengths, allowing it to focus on light that can be reflected by a planet emitted by a star.

The PDS 70c is a little smaller, about 1 to 10 times the mass of Jupiter. It is also farther away – about 34.5 to the south (5.31 billion kilometers) and its orbital period is almost exactly double that of PDS 70b. For every 70b orbit, 70c does only once.

The PDS 70c was discovered using a different instrument, the VLT's MUSE spectrograph, with a new mode allowing the telescope to capture a hydrogen signal – a signature of gas accumulation, such that you could to see her on a giant planet in gas formation.

This mode was not intended at all for exoplanet hunting, but for the study of galaxies and star clusters. But the discovery highlights a new potential way of trying to identify exoplanets still in formation within protoplanetary disks.

"We were very surprised when we found the second planet," said astronomer Sebastiaan Haffert of the Leiden Observatory.

This is the kind of surprise we can all enjoy.

The search was published in Nature Astronomy.

[ad_2]

Source link