[ad_1]

In a galaxy with at least a few hundred billion stars, you can expect some of them to be weird.

For some time, it seems that the star of Tabby – a star that has experienced strange dives in its starry light that proved extremely difficult to explain – was unique among the population of the Milky Way. No other star has presented the same behavior.

But maybe we were not looking hard enough. Another star appeared with similar behavior, and it may even more weird. In addition, a survey of several million stars revealed a total of 21 additional stars that could behave the same way. And up to now, there is still no explanation covering all the basics.

But what is happening here?

Agree, first of all, a brief criticism: KIC star 8462852 is found in a part of the sky observed by the Kepler Space Telescope, which looks for troughs in starlight because of planets orbiting the stars. If the orbit of a planet is lined, we see a periodic drop in starlight when the planet blocks a small fraction of the star's surface. These usually occur in stable and reproducible patterns, once per orbit.

But KIC 8462852 had recurring lows, and worse yet, some of the declines were huge. Usually, you get a small fraction of light drop percentage, but at one point, the light of this star has dropped by 22%. C & # 39; huge, and can not come from a planet (such a big planet would be a star). Scientific citizens have spotted these holes in the Planet Hunters project. The responsible astronomer was Tabetha Boyajian, and she was the lead author of a newspaper announcing the strange star (which is why it is called "Boyajian Star" or in the more popular "Tabby Star" press; last, but I prefer the first and will continue from here this way).

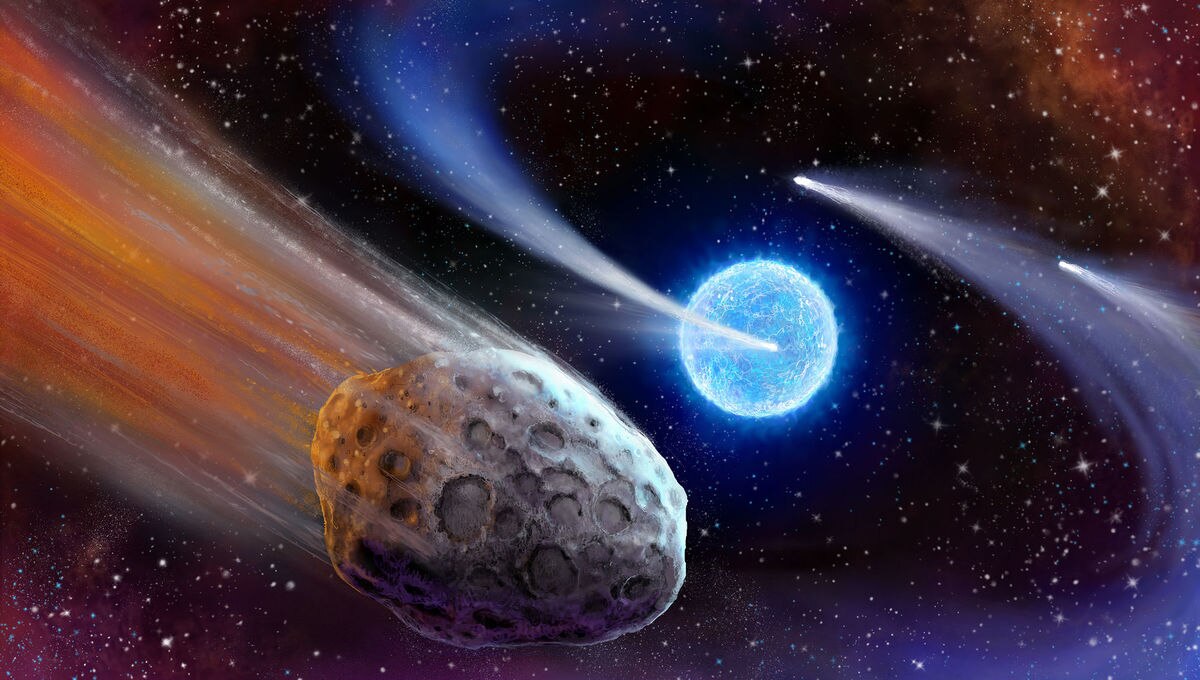

Numerous explanations have been put forward, including strange planets, dust clouds, comets, and so on. Yes, including foreign megastructures. But a big breakthrough occurred in early 2018 when astronomers announced that the troughs were deeper in the blue light than in the red. That's what you expect from dust clouds, which block blue light more effectively than red. However, how exactly does it work in this case has not yet been fully developed (you can read my blog post from the moment I explain it all).

It's really hard to understand a phenomenon like this, so strange, when you only have one example. What we really need is more stars that show this behavior. For a long time we did not know it.

Now maybe we do. In June 2019, a team of astronomers published an article on star HD 139139, which he called "Transiting at random". It also indicates the hollows, but no matter how you cut it, the hollows seem random over time. But it gets stranger: with the exception of two of the 28 observed hollows, they all seem to have roughly the same depth, darkening the star by about 0.02% each time. This implies that objects passing through the star are all the same size, which is weird. Even worse, the length of transits is everywhere too. Some last an hour, others more than 7 hours.

The star itself can be a binary; a much weaker second star is near in the sky and both can turn around one of the other. It is not clear if the transit is occurring with the brightest or weakest star; If it is the brightest, the objects all have a size about 1.5 times greater than that of the Earth. If they gravitate around the dimmer star, they are taller, and look like one or two times the size of Jupiter.

After an exhaustive analysis of the schedules, it is possible (though unlikely) that four of the transits may come from a single repeating object, but that the other troughs remain unexplained. The team notes that the troughs are so random that they could have been taken from a random number generator. What could do that?

Astronomer Hugh Osborn examines all known possibilities in a blog post and arrives empty. It gives a good summary of the situation, however, it is worth reading. Planets, asteroids, planets and asteroids enveloped in clouds of dust, comets … these explanations cover part of the data, but not all. Nothing seems to explain all the strange things that happen in this star. That, plus the seriously random nature of the troughs, leads Osborn to conclude that HD 139139 is even stranger than Boyajian Star. At least here, we know that dust is involved in one way or another.

This would help a lot to find more stars like these. This led the astronomer Edward Schmidt to search databases from vast polls of stars to see if other stars had such strange behavior. He has reviewed several surveys covering several million stars and discovered … 21. These stars all had strange, seemingly random dives, and some of them also showed quite significant drops in light. Curiously, he discovered that they tended to belong to two groups: normal stars with about the same mass as the Sun and red giants, stars near the end of their life, with about twice the mass of the Sun.

For me, it is not clear that there is a strong correlation, but it is enough to be interesting and certainly deserves a follow-up. It is clear that this is the case – that all of these stars, including Boyajian Star and HD 139139, belong to these two groups – this implies that some intrinsic characteristics of the two – star play a role. Maybe this kind of stars have planets that can do these troughs one way or another or that the star itself is doing something really strange that makes clocks more difficult to understand.

Since we know that an external dust is involved in Boyajian Star, it is difficult to reconcile something intrinsic with the star itself, but the fact is that there are many things we do not understand of what is happening here. The best thing that can happen now is that larger, more sensitive telescopes are watching these stars as often as possible, to look for anything from their light that can give clues to the origin of these peculiarities. Once we have enough observations, we can start looking for patterns, and that's when you can start preparing a case for the physical nature of these bizarre stars.

Hope that other stars like these will be found. More the merrier, the merrier! I like a mystery, but I think this one has been going on for quite a long time now. It would be nice to start getting solid answers.

Tip of the Dyson sphere to Jason Wright to tell me about HD 139139. In addition, after writing this article, but before its publication, I saw that the AAS Notes website posted about this too! This site deals with research published in American Astronomical Society journals and is worth following if you want to read somewhat more technical descriptions of astronomical work.

[ad_2]

Source link