[ad_1]

Sixteen days apart last month, Princess Secret and Robinson Canó tested positive for the same performance-enhancing steroid, stanozolol. Princess Secret is a two-year-old filly who had won three of her five career races before being kicked out of the Breeders’ Cup. Canó was sent off from baseball for 162 games.

The fact that a 38-year-old second baseman on his last contract with $ 214 million already in the bank chose to use the same, easily detectable old-school steroid that was given to a thoroughbred 1000 pounds tells you that steroid use in baseball will never go away. So far, Canó has offered as many explanations for his transgression as the horse.

Stanozolol, sold under the brand name Winstrol, is the worst type of PED if your goal is to avoid detection. It leaves a unique fingerprint and is detectable for several weeks to a month when taken in pill form.

Rather than squeezing out huge muscles, its main benefit is increasing blood oxygen levels, which increases endurance. It also adds lean muscle mass by removing water from the body. It tends to be favored by older players and pitchers later in a season and typically requires several weeks of use to generate effects. In 1988, it was sprinter Ben Johnson’s drug of choice.

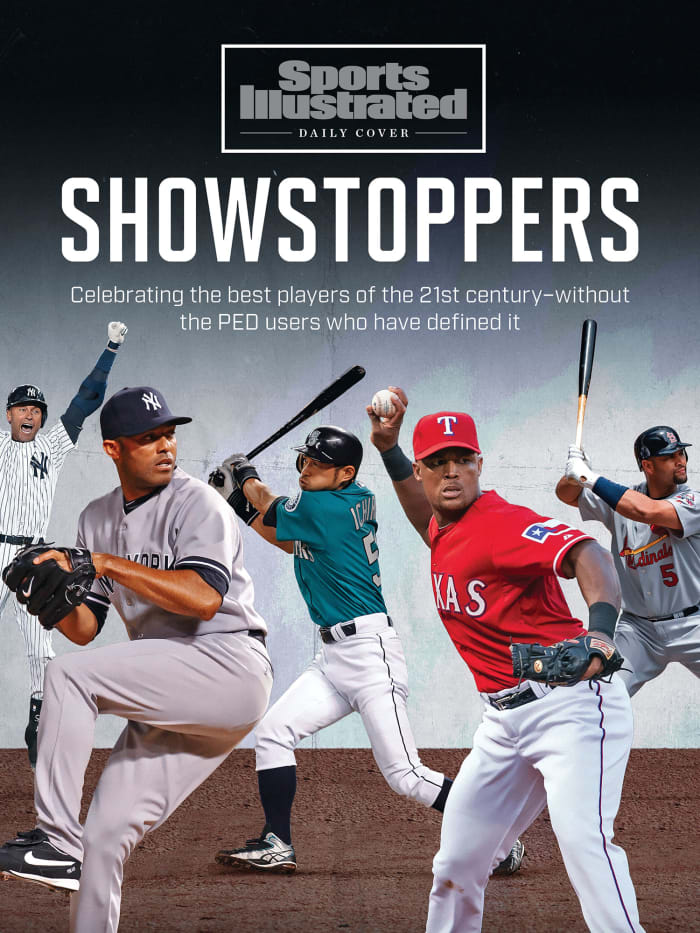

I thought of Canó, steroids, and the historic complications of DCs in putting together an All-Century team far too early. We’re in 21 seasons, which is enough time to have fun picking the best players in each position so far in the 21st century.

Steroids have zapped some of the joy of exercise, just like they have the record books, the way we compare players from different eras, and the game itself. Testing for steroids with penalties began in 2004. Yet the shadow of PED users continues to be long.

Canó, for example, has the sixth greatest WAR (68.9) of any player this century, the best by a second baseman. But his other Hall of Fame numbers don’t mean much. He’s a two-time delinquent. Like others arrested for steroids, he will one day leave the game with the equivalent of a dishonorable discharge. He can keep his money (but not his $ 24 million salary in 2021) and his artificial numbers. They are immutable. But the same goes for his reputation.

It’s not just Canó. As I began to assemble my All-Century squad, I was surprised at how many otherwise-considered ‘big’ players I eliminated because their numbers are far from authentic.

Of the 31 players who have hit the most home runs this century, seven of them are known PED users. That’s 22.5% of the greatest sloths this century, even with tests in place for 17 of the 21 seasons.

This year has been one of baseball’s particularly deep and painful losses: Al Kaline, Tom Seaver, Lou Brock, Bob Gibson, Whitey Ford and Joe Morgan. As tributes and memories poured in, none had to be expressed as “yes, but…” when it came to their accomplishments.

The six late legends were all nominated for the All-Century team in 1999. Kaline, Seaver, Brock, and Ford did not. Roger Clemens and Mark McGwire did it.

Three years later, with the SI special report on steroids in baseball, the era of discovery began. Testing has cut back on the days of rampant steroid use in the Old West, but it hasn’t and won’t stop it.

It should be noted that Canó’s bust occurred the same week the Hall of Fame ballots were sent to baseball writers. There’s a reason players and owners agreed to a program that bans steroid use and punishes violators without pay – and why there is a horse racing integrity and safety law. The reason is that the foundation of sport is fair play. Those who willfully (and usually repeatedly) violate the most basic precept of competition jeopardize the right to be honored in the same way as those who have competed fairly.

No known steroid user was on my All-Century team. Players have been considered in positions where they have appeared in at least half of their games this century (with exceptions noted).

Catch: Yadier Molina

Second team: Buster Posey

They have almost played their careers. From 2009 to 2018, 28 places were filled in the National League All-Star teams. Molina and Posey took 15, two more than all the other catchers in the league combined. Posey’s war this century is 41.8. Molina’s WAR is 40.8. The separator here is the volume. Molina played 767 more games than Posey with 621 more hits.

First base: Albert Pujols

Second team: Miguel Cabrera

Pujols made his debut in 2001. He is the leader of the century in home runs (662), hits (3,236), races (1,843), RBIs (2,100) and war (100.6 ), and it’s not close. (Hank Aaron led the last century in homers and RBIs, Ty Cobb in races, Pete Rose in hits, and Babe Ruth in WAR.) It took a bit of rule-playing to get Cabrera in the game. team ahead of Joey Votto and Todd Helton. Cabrera (fifth overall in WAR) has played 46% of his first goal matches. I rounded up.

Second goal: Chase Utley

Second team: Ian Kinsler

A player with a high peak and low longevity, Utley will be an interesting Hall of Fame case when he goes to the poll in 2023. A peerless defender and baserunner, he is eighth in WAR’s overall standings this century (64.4 ). Kinsler (55.2) ranks third among second baseman. Utley played 16 seasons, but played 140 games just five times.

Shortstop: Derek Jeter

Second team: Jimmy Rollins

Jeter and Rollins rank 1-2 in WAR, Races and Hits. The current elite shortstop class does not yet approach Jeter and Rollins’ volume. Francisco Lindor, for example, leads the current shortstops with 138 homers and Elvis Andrus leads with 1,743 hits. These are far from the Jeter totals this century (197 and 2,658).

Third base: Adrián Beltré

Second team: Chipper Jones

Beltré, which started in 1998, is an easy choice because of the quality and volume of its work. Despite 2012 as his final season, Jones led all other third baseman in OPS and WAR, nodding against Evan Longoria, Aramis Ramírez, Scott Rolen and David Wright.

Left Field: Matt Holliday

Second team: Christian Yelich

Barry Bonds, Ryan Braun and Manny Ramirez have placed 1-2-4 in WAR at the position this century. Holliday was a career .300 hitter at the start of September of his final season (rounded to .29958). He had just four hits in his last 26 at bats to finish at .29904. Yelich’s MVP gives him the edge over Alfonso Soriano, Carlos Lee, Alex Gordon and Brett Gardner.

Center Field: Mike Trout

Second team: Carlos Beltrán

Trout only played for half a decade, but is the out-of-control leader of WAR. Beltrán’s apparent leadership role in the Astros sign-stealing scandal needs more explanation from him.

Right field: Ichiro Suzuki

Second team: Vlad Guerrero

With 3,089 hits in 19 years, Suzuki is another obvious choice. Mookie Betts closes the gap in WAR over Guerrero (45.9–45.2), but Guerrero beats him in volume and hitting rate stats (average, based, slugging). Surprisingly, Bobby Abreu, JD Drew and Jason Heyward all make the top eight in WAR.

Designated Hitter: David Ortiz

Second team: Jim Thome

Wait. Didn’t Ortiz test positive for steroids in investigative testing in 2003? Yes and no. Ortiz’s name was one of the few that was leaked by law enforcement sources among a list of 103 players identified as positive. But Ortiz’s case was the only one among those named players that the players association and the commissioner’s office defended as unverified. Once the union and MLB agreed to check enough positive tests to trigger testing in 2004 (5%), they didn’t bother to check for the excess – anywhere from 10 to 15 tests. The late AP Director Michael Weiner said legal supplements at the time could trigger an unverified positive effect. In an unparalleled defense by the MLB, commissioner Rob Manfred gave Ortiz a pass in 2016, referring to “legitimate science questions” about the test results of surplus players. Manfred said of Ortiz: “I know he’s never been positive at any point in our program. Thome has played 47% of his matches at DH (another rounding exercise).

Starting pitcher: Justin Verlander

Second team: Clayton Kershaw

CC Sabathia won the most games, pitched the most innings and struck out the most batters, but fell short of the sustained level of excellence of Verlander (No. 1 in WAR) and Kershaw (No. 1 in the FIP, tied with Jacob deGrom), who combined for five Cy Young Awards and two MVPs. Special mention to the late Roy Halladay, who completed 65 starts, more than Verlander and Kershaw combined. No one else had more than 39.

Relief pitcher: Mariano Rivera

Second team: Craig Kimbrel

Rivera was 30 when the decade began and he is by far the best reliever of the century, with 86 more saves than Francisco Rodríguez, No 2 on the list, and by far the best in terms of adjusted ERA (217) . One of Rivera’s many unique superlatives: It launched 13,549 slots this century and only launched eight wild slots, or roughly one in every 1,700 slots. Kimbrel edged Billy Wagner for the second team, with advantages in FIP, takedowns, ERA and saves.

To learn more about SI’s daily coverage, click here

[ad_2]

Source link