[ad_1]

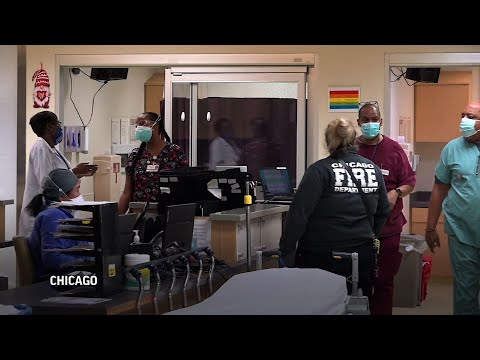

CHICAGO (AP) – At a makeshift vaccination center at a Chicago hospital, a patient services assistant leads an older woman with a cane to a curtain booth.

“Here, sit here,” Trenese Bland said helpfully, preparing the woman for a vaccine that offers protection against the virus that has ravaged their black community. But the aide has doubts about his own vaccination.

“It’s not something I trust at the moment,” says Bland, 50, who is concerned about how quickly COVID-19 vaccines have been developed. “It’s not something I want in myself. ”

Only 37% of the 600 doctors, nurses and support staff at Roseland Community Hospital have been vaccinated, even though health workers are the first. Many recalcitrant come from the predominantly black and working-class neighborhoods surrounding the hospital, areas hard hit by the virus but prey to reluctance to vaccination.

The irony has not escaped the notice of the organizers of a vaccination campaign at the 110-bed hospital, which until recently was teeming with coronavirus patients. If seeing COVID-19 up close and personally isn’t enough to persuade people to get vaccinated, what will it do?

The resistance confuses Dr Tunji Ladipo, an emergency room doctor who has seen the disease devastate countless patients and their families, and frequently works side-by-side with unvaccinated colleagues.

“Why don’t people who work in health care trust science? I don’t understand that, ”he said.

Health experts have stressed the safety of the vaccines, noting that their development was unusually rapid but based on years of previous research and that those used in the United States have shown no signs of serious side effects in studies. involving tens of thousands of people. But a history of abuse has contributed to mistrust of the medical establishment among some black Americans.

In a recent poll According to the Associated Press and the NORC Center for Public Affairs Research, 57% of black Americans said they had received at least one vaccine or planned to be vaccinated, compared to 68% of white Americans.

Black Americans interviewed by the National Foundation for Infectious Diseases cited reasons for reluctance to vaccinate that echoed those of Roseland employees.

The no-frills, five-story red-brick hospital opened nearly a century ago in Chicago’s far south. Adjacent to a mall, auto parts store and gas station, its backyard is a residential street teeming with timber frame houses and three-apartment buildings.

The doctors, nurses and staff are almost all black, as are the patients.

It would be hard to imagine anyone not being aware of the staggering health inequalities that plague the city’s black community and others across the country.

Blacks make up 30% of Chicago’s population but, at the onset of the pandemic, more than half of deaths from COVID-19. This gap has narrowed, although the disease disparities that explain this risk persist, including high rates of hypertension, diabetes and obesity. Blacks are more likely to have jobs that don’t provide health insurance or the luxury of working safely from home during a pandemic.

Neighborhoods on the south side are lagging behind wealthier whites in securing COVID-19 testing sites and recent data from the city shows COVID-19 vaccinations among black and Latino residents are far behind. white residents.

Without enough takers among hospital staff, Roseland donated some of his doses to city police and bus drivers. Hospital representatives scramble to find ways to raise awareness and increase its immunization rates – posters, stickers, training sessions.

They even recently brought in a Civil Rights veteran, Reverend Jesse Jackson, to get his first photo on camera.

“African Americans were the first to fall victim to the crisis, cannot be the last to seek a cure,” Jackson said before his inoculation.

Dr Kizzmekia Corbett, a black scientist in the US government who helped develop Moderna’s vaccine, accompanied Jackson. She acknowledged “centuries of medical injustice” against black Americans, but said COVID-19 vaccines were the result of years of solid research. Confidence in these vaccines, she said, is necessary to save lives.

Rhonda Jones, a 50-year-old nurse at the hospital, has treated many patients with severe COVID-19, a relative has died, and her mother and nephew have been infected and cured, but she is still holding on.

The vaccines “came out too quickly” and were not properly tested, she said. She doesn’t rule out getting vaccinated, but not anytime soon.

“I always tell my patients, just because a doctor prescribes you medication, you have to ask; you don’t take it just because, ” Jones said. “Nursing school teachers have always told us, when in doubt, to check,”

At the start of the pandemic, the hospital cafeteria closed for two months when a worker was infected. Yet hospital administrator Elio Montenegro said that when he asked cafeteria staff about getting the vaccine, “everyone said, ‘No, I don’t understand.'”

Adam Lane, a cook, said he did not trust the US government. He believes political pressure has rushed vaccines to market and fears that those given to black communities are different and riskier than those offered to whites.

“I am tired of COVID. I think we all want this to be over, ”Lane said. “But I don’t want to waste my soul for a quick vaccine. ”

Roseland obstetrician and infection control specialist Dr Rita McGuire says tackling misinformation and mistrust of vaccinations is a daily struggle. Many workers “haven’t forgotten about these studies where they used us as experiments,” McGuire said, including the infamous Tuskegee research. on black patients with syphilis.

Many are also worried about the serious side effects of the vaccine, but these are extremely rare, McGuire tells them.

Some say they will wait until spring or summer to get the vaccine. With infection rates still high and the emergence of more contagious virus variants, “it’s too late,” McGuire said.

___

Follow AP medical writer Lindsey Tanner on @LindseyTanner.

___

Associated Press Department of Health and Science receives support from the Department of Science Education at the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. The AP is solely responsible for all content.

[ad_2]

Source link