[ad_1]

Copenhagen in February 2020.

Photographer: NurPhoto / NurPhoto

Photographer: NurPhoto / NurPhoto

Vaccines are rolling out, slowly but steadily, across the world. Does that mean there is still time to think about traveling?

The tourism industry would like to say yes. According to the most recent data from World Travel and Tourism Council, released in early November, travel restrictions caused by the coronavirus pandemic are expected to remove $ 4.7 trillion from global gross domestic product in 2020 alone.

But healthcare professionals still urge caution – a message that will remain imperative, even after individuals have been vaccinated against Covid-19.

Among their caveats: vaccines are not 100% effective; it takes weeks to develop immunity (after the second injection), little is known about the ability to transmit Covid-19, even after vaccination; and the immunity of the flocks will still be a long way off. Their consensus is that the risks will remain, but that freedom of movement can safely increase – allowing at least some types of travel – among those protected from the virus.

Yes, you will still need to wear a mask.

Here’s what else you’ll need to know about travel safety in the coming months, whether you’ve already pulled off your photo or are looking for normality somewhere on the horizon.

What we know and what we don’t know

The Covid-19 vaccines approved to date, in the United States and Europe, have been shown to be exceptionally safe, effective and the most powerful tool yet to fight the pandemic. However, there are known unknowns, especially regarding the possible transmission of the virus after vaccination.

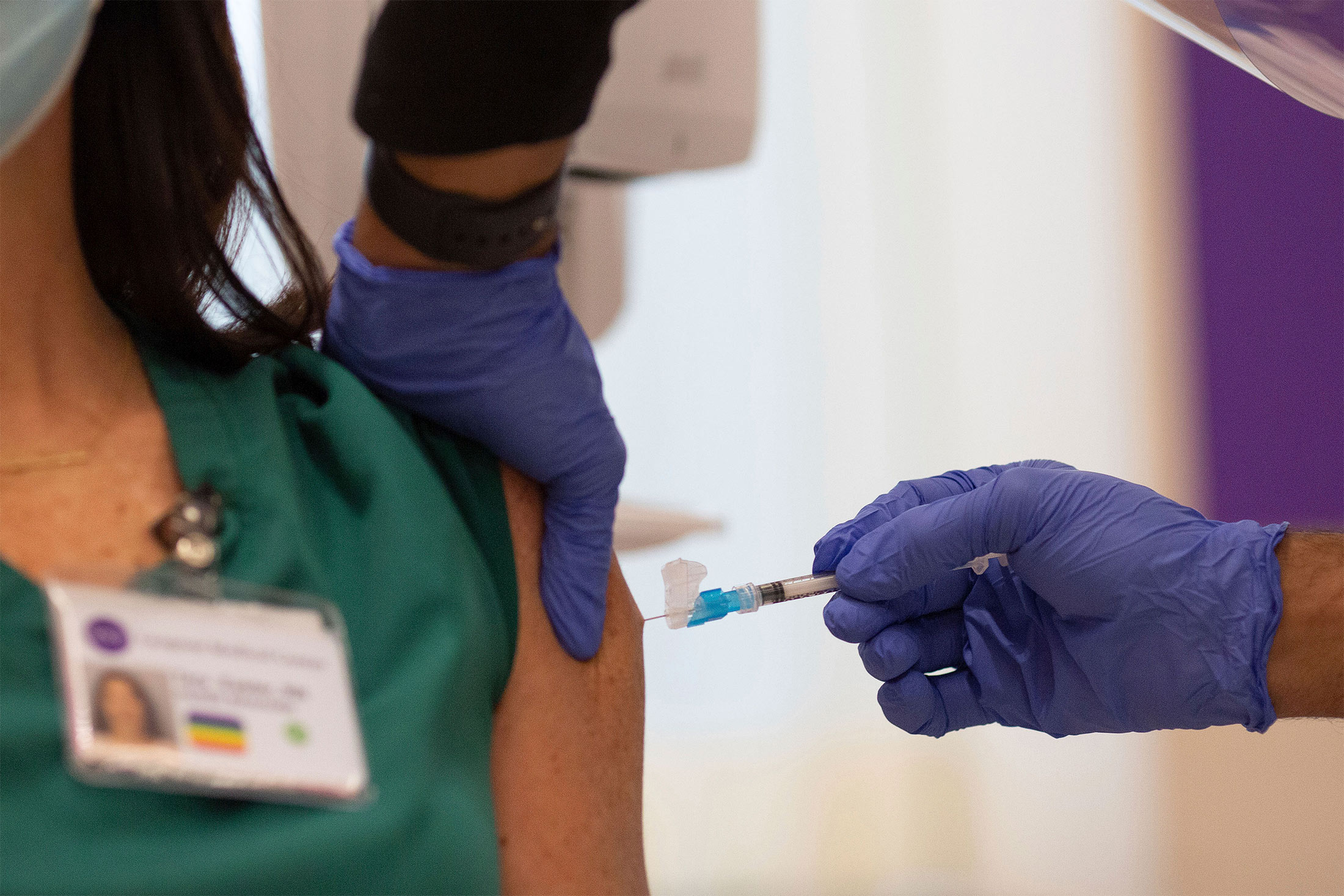

A nurse administers a vaccine at NYU-Langone Hospital in New York.

Photographer: Kevin Hagen / AP

This question comes down to one point: Clinical trials for currently approved vaccines, including those from Pfizer and Moderna, did not include regular PCR testing of study participants. In the absence of data on their ability to carry the virus, there is enough conclusive evidence to suggest that vaccines offer 95% effective protection against symptomatic infections, says Dr. Kristin Englund, an infectious disease specialist at Cleveland. Clinic.

“For the most part, if you are vaccinated against [a disease]- let’s say chickenpox or measles – you shouldn’t be able to pass this virus on to anyone else, ”explains Englund, adding that there is no known reason to believe that Covid-19 or its combined vaccines should behave differently. “I predict that’s what we’ll see [with Covid-19 vaccines as well], but we have to wait for studies to prove it before we can lower our guard significantly.

There are other important unknowns as well. “To see a vaccine 95% effective – these are remarkable numbers, much better than we ever imagined,” says Englund. “But we don’t have the capacity at the moment to know who will have a good answer [to the vaccine] and who will be part of the 5%. “

How to think about herd immunity

Another unknown, to a lesser extent, is what it will take to obtain collective immunity.

“The general consensus is that it will take between 70% and 80% [of the population being immune] to eliminate the pervasive risk – maybe more, ”says Dr. Scott Weisenberg, who is both director of the infectious disease scholarship program at NYU and medical director of the university’s travel medicine program. “We’re several months away from that, assuming the vaccine actually suppresses transmission and people get it.”

In the best-case scenario, Weisenberg believes herd immunity can be achieved in the United States this summer – pending approval of easier-to-distribute vaccines such as that of AstraZeneca, which could accelerate the deployment.

It is highly unlikely, however.

“Acceptance of the vaccine is a big key question,” he adds. In this regard, the World Health Organization has called reluctance to vaccinate as one of the Top 10 threats to public health in 2019, even before Covid-19 was part of the picture.

But collective immunity can be sliced and diced in several ways.

“You can talk about collective immunity within a state, within a small community, or even within a family,” Englund adds. “So if everyone in a room is vaccinated except one, you should be able to provide more protection for that person.”

This is a notable consideration for family reunions where younger members may take longer to qualify for the vaccine than older or more at-risk members. (Currently approved vaccines have not yet been tested or approved for children by the United States Food and Drug Administration, which could prevent air travel among multigenerational groups until 2021.)

A Kenya safari might seem like a good socially remote vacation option, but you might want to consider your transfers.

Source: Original Africa

Decide where to go on your next vacation – and who to travel with – may have more to do with antibodies than normal considerations such as weather and price.

“Definitely look at the current infection rate in this area and absolutely, the vaccination rate in this population – those are two very important things,” Englund says.

Don’t be surprised if this sounds like a counterintuitive exercise, Weisenberg adds.

For example, in New York City, where 25% of the population is said to have already contracted Covid-19, herd immunity may require a proportionately smaller number of vaccinations if previously infected people retain equivalent antibodies.

“The risk [of picking up or spreading the virus] could in fact be relatively low, ”Weisenberg says of his visit to Manhattan, given the stringency of the lockdown measures, the historic acceptance of vaccines in urban versus rural areas and the high rates of Covid-19 testing among the local population – despite the incredible population density.

Go to Kenya, where you can have a perfectly socially remote safari, he adds, and you may have to go through places like Nairobi, where the tests are weak and it is difficult to get an accurate picture of the risk in real time.

The evolving definition of “safe travel”

Expect the definition of safe travel to change from week to week, especially as parts of the world resist the surge in cases related to vacation travel and new variants of the virus.

“You have to take into account the issues of going somewhere and bringing the virus back to an area where it has consequences,” Weisenberg says. He hopes the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention will eventually have tiered alerts for destinations, based on local risk, in line with the agency’s measles alerts, but says, “C ‘ is just too common right now to be isolated in this way. ”

A good idea might be to check the availability figures for hospitals (and especially intensive care beds) before taking vacations anywhere, to make sure the local system is not already overwhelmed.

A Delta plane being disinfected.

Photographer: Michael A. McCoy / Getty Images North America

Weisenberg also believes that the increasing accuracy of rapid Covid-19 antigen testing will help ensure safety as mobility increases; it should be noted that the new entry requirements for the United States include negative test results, even for those who have already been vaccinated.

“I’m going to get on a plane; I’ll be honest with you, ”Englund says. “I’m going to wear a mask, I’m going to make sure we have seats where we’re not sitting next to someone else, with proper space in between, using all the hand sanitizer.

“We’ll have an Airbnb and spend some quality time on a beach,” she continues, “and if we visit local sites, we’ll pretend we haven’t been vaccinated – approaching things with the same precautions we do. would have had pre-vaccine. I don’t think there is anything wrong with it.

[ad_2]

Source link