[ad_1]

Most of us know that the cannabis plant produces compounds that react with the human body. This is because we have our own system that makes similar compounds, the cannabinoids, which have a wide range of actions from appetite control to immune function. Cannabis contains a cannabinoid called THC, which interacts with the brain, resulting in euphoria and relaxation, as well as increased hunger and anxiety.

It has long been thought that there was no other natural source of cannabinoids – and with a long list of uses supposedly for medical purposes, the mythical power of cannabis and the psychoactive properties of THC have increased .

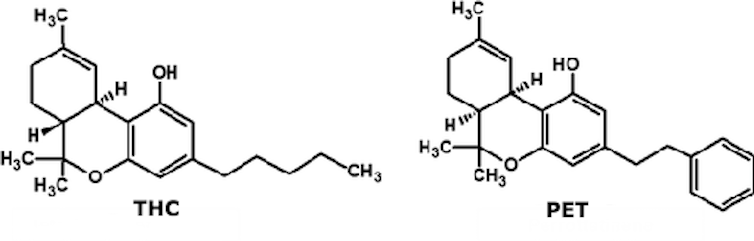

But it has turned out that another plant contains something similar: a compound that has the structural features allowing it to act on the brain in a similar way to THC.

The discovery of this lost twin, called cis-PET (perrottetinene), or PET, was hidden in chemistry journals in articles published in 1994 and 2002, no further research confirming its biological activity. But in a new study published in Science Advances, a group of Swiss scientists looked into the mechanism by which PET might act on the brain.

The hepatic in question, radula, is endemic to New Zealand and Tasmania and is used by Maori as a herbal medicine. The preparations using this plant are also sold as a legal internet high of the THC type.

Although similar to THC, does PET produce the same effects as THC at the cellular and molecular level? Does this mimic the physiological effects? And is it different in a way that could give it a therapeutic advantage or disadvantage? Some 24 years after its first discovery, the team of chemists and biochemists behind the new study looked at some of the answers provided.

Their research was not a small feat. A new synthesis method was needed to produce enough PET to perform meaningful experiments. Once this goal was achieved, the researchers examined two mirror versions of the two compounds, cis (the version found in the hepatic) and trans (a version created artificially in the laboratory). In chemistry, the cis and trans the terms tell us on which side of the carbon chain are the functional groups (the bit of the molecule that does the work).

The researchers wanted to know if these two versions of PET were able to interact with the two receptors found in humans that mediate the psychoactive effects of cannaboids – CB1, the receptor that produces the "high" effect of THC, and CB2 – in the same way as the THC (their binding strength and the amount needed to produce an effect).

The researchers found interesting similarities between the two PET and THC versions. For PET and THC, the trans versions (the abundant THC version found in cannabis and the synthesized laboratory version found in the hepatic) bind better to the CB1 receptor than the cis versions.

What is interesting is that even if the levels of cis-PET found in the liver are too low to produce the "high" effects produced by THC (that's why smoking PET will only produce not a high effect), this could explain why PET could still have a medicinal effect (similar to the effect produced by a lower dose of THC). However, any method of extracting and concentrating the liver compound could lead to the same problems as THC.

But what about CB2, the other cannabinoid receptor? This receptor plays a role in immune responses. Here, Swiss scientists have found that the cis versions of THC and PET related to this receptor better than the trans versions. The implications of this are not yet explored, but it still suggests a potential medicinal benefit to explore further.

The authors of the study then verified whether the binding of CB1 receptors in mouse brains had the same recognizable effects of THC. Usually, when THC binds to this receptor, it produces four key effects: a decrease in body temperature, muscle rigidity, decreased movement, and decreased sensitivity to pain. In this behavioral test, the four effects were also obtained in mice using cis-PET, but in a much larger amount.

But there was a noticeable difference. Inflammation in the brain is caused by molecules called prostaglandins that can be derived from metabolic pathways involving our own body, cannabinoids or plant derivatives. transTHC. On the other hand, the production of these mediators has been reduced by cis-PET. It remains to be seen if it is a good or a bad thing.

So while the study is only a beginning for understanding the mechanisms and effects of PET on the brain, there are many things we do not know yet. What we do know now, however, is that the concentrations of PET found in natural agriculture are too low to produce the known effects of THC, so it is unlikely that it will smoke smoking.

But it is also interesting to note that this compound may well have medicinal benefits without the highest factor – one of the main reasons why THC has already been rejected as a drug. Illicit trade and cultivation have confused many significant clinical research, but this is changing and this new compound will add to the treasure of plant-derived cannabinoids that we still have a lot to understand.![]()

Karen Wright, Lecturer in Biomedical and Life Sciences, Lancaster University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

[ad_2]

Source link