[ad_1]

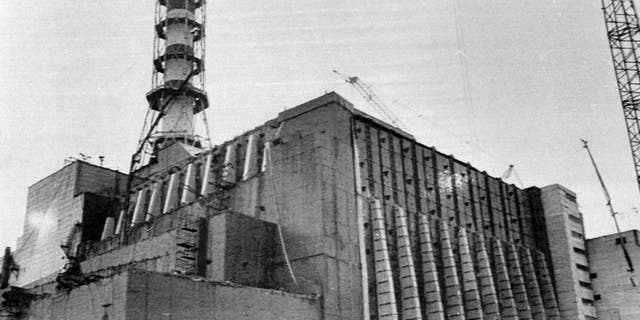

Photo taken in 1986 of an aerial view of the Chernobyl nuclear power plant in Chernobyl, Ukraine, showing the damage caused by an explosion and fire in the No. 4 reactor on April 26, 1986, which sent large quantities radioactive material in the atmosphere.

(AP / File)

A dangerous "time bomb" of radioactive fallout from nuclear smelting and weapons testing is about to be launched around the world.

Researchers have found traces of nuclear fallout in glaciers around the world – frozen, but at risk of being released.

A team of international scientists has studied nuclear fallout around the world.

CLICK ON THE SUN FOR MORE

They examined the presence of these radioactive materials in ice sediments in the glaciers of the Arctic, Iceland, the Alps, the Caucasus Mountains, British Columbia and the United States. ;Antarctic.

And it appeared that "artificial" radioactive material threatened the 17 sites studied.

Worse, the concentrations were at least 10 times higher than those observed elsewhere.

"They are among the highest levels seen in the environment outside of nuclear exclusion zones," said AFP Caroline Clason, of Plymouth University.

Most nuclear fallout falls back to the ground as acid rain – which is usually absorbed into the soil.

But in colder climates, radioactive material can fall into the form of snow and settle in the ice, where it forms a heavier sediment.

This accumulates in the glaciers and concentrates the nuclear residue levels.

And major nuclear incidents – such as the 1986 Chernobyl disaster – can spread radioactive material far and wide.

The reactor number four of the Chernobyl nuclear power plant is visible in this archive photo of December 2, 1986, after the completion of the work to bury it in the concrete as a result of the l '. explosion of the plant. (Reuters)

"The radioactive particles are very light, so they can be transported for a very long time in the atmosphere," explained Caroline.

"When it falls in the rain, as after Chernobyl, it disappears and is a kind of unique event.

"But in the form of snow, it stays in the ice for decades and melts in response to the climate, it is then dragged downstream."

The Clason team was also able to detect some of the fallout from Japan's Fukushima nuclear fusion in 2011.

However, researchers determined that it was still too early for most fallout to occur on the ice after the disaster.

The study also highlighted significant amounts of spinoff from nuclear weapons testing.

"We are talking about gun trials from the 1950s and 1960s, dating back to the early days of bomb development," said Caroline.

"If we take a core of sediment, you can see a clear tip where Chernobyl was.

"But you can also see a fairly definite peak around 1963, at a time of relatively heavy weapon testing."

As global temperatures rise, there is a growing risk that nuclear fallout will be released around the world.

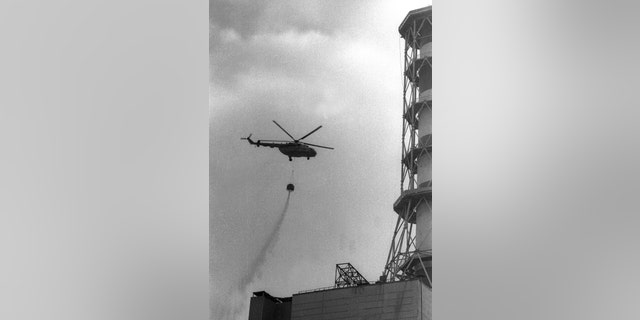

A helicopter dropping concrete on the fourth reactor of the Chernobyl nuclear power plant after its explosion appears in this 1986 photo archive. (Reuters)

(Reuters)

This could potentially contaminate food and water supplies – although the study did not focus on the impact.

It is therefore currently impossible to say to what extent the melting of radioactive glaciers puts human life at risk.

What we do know is that the radioactive materials that hide in the ice are extremely dangerous.

One of these materials is americium, a radioactive residue produced during the decay of plutonium, which can last 400 years.

"Americium is more soluble in the environment and it is a stronger alpha [radiation] transmitter, "explained Caroline.

"These two things are bad in terms of integration into the food chain."

She added that americium is "particularly dangerous" and explained that these nuclear materials would be a marker of the impact of humanity on the planet for generations to come.

"These materials are a product of what we put in the atmosphere," warned the scientist.

"It just shows that our nuclear heritage has not disappeared yet, it is still there.

"And it is important to study this because it is ultimately a mark of what we have left in the environment."

This story originally appeared on The Sun.

[ad_2]

Source link