[ad_1]

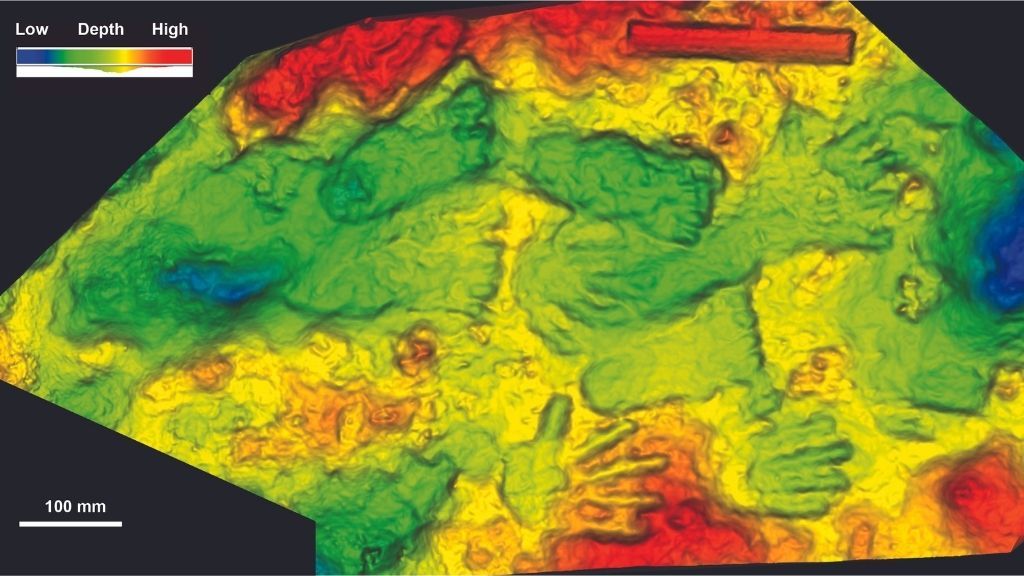

About 200,000 years ago, Ice Age children crushed their hands and feet in sticky mud thousands of feet above sea level on the Tibetan Plateau. These prints, now preserved in limestone, provide some of the earliest evidence of human ancestors inhabiting the area and may represent the oldest art of their kind ever discovered.

In a new report, published on September 10 in the journal Scientific Bulletin, the authors of the study argue that the hand and footprints should be considered “wall” art, that is, prehistoric art that cannot be moved from place to place. to the other ; this usually refers to petroglyphs and paintings on cave walls, for example. However, not all archaeologists would agree that the new engravings meet the definition of cave art, an expert told Live Science.

Traces left by the children of the Ice Age

Study author David Zhang, professor of geography at the University of Guangzhou in China, first spotted the five handprints and five footprints during an expedition to a fossil Quesang hot spring, located over 4000 meters above sea level on the Tibetan plateau. The authors dated the sample by assessing how much uranium, a naturally occurring radioactive element in the environment, could be found in the fingerprints. Based on the rate at which uranium decays, they estimated that impressions were left about 169,000 to 226,000 years ago – right in the middle of the Pleistocene period, which occurred 2.6 million to 11,700 years ago.

Related: Photos: Searching for extinct humans in the mud of an ancient cave

And judging by the size of the footprints, the team determined that the marks were left by two children, one the size of a modern 7-year-old and the other the size of a child. 12 years old. That said, the team cannot know which species of archaic human left the footprints, said study co-author Matthew Bennett, professor of environmental and geographic sciences at Bournemouth University in Poole, England.

“Denisovans are a real possibility”, but Man standing was also known to inhabit the area, Bennett told Live Science, referring to a few known human ancestors. “There are a lot of suitors, but no, we don’t really know.”

The footprints provide the first evidence of hominids in Quesang, “but there is growing evidence that archaic humans were around the Tibetan Plateau around the same time,” Bennett added. For example, scientists recently recovered a Denisovan jaw from the Baishiya cave, located at the northeastern end of the Tibetan plateau, said Emmanuelle Honoré, postdoctoral researcher at the Free University of Brussels in Belgium, who did not did not participate in the study. The mandible is “at least” 160,000 years old, researchers in 2019 reported in the journal Nature, which means the bone remains could date back to the same time period as Quesang’s handprints, Honoré told Live Science in an email.

That said, Baishiya Cave is several kilometers north of Quesang and is just 10,500 feet (3,200 m) above sea level, so the new handprints provide the oldest evidence of occupation in the central and uppermost region of the plateau, said Michael Meyer, assistant professor of geology at the University of Innsbruck in Austria, who was not involved in the study. Like the authors of the study, Meyer suspects that the Denisovans probably left the prints of their hands, so “the study could thus indicate that the Denisovans were the first Tibetans and that they originally adapted genetically for dealing with the stress of high altitudes, ”he told Live Science in an email. .

The handprints themselves are made of travertine, a kind of freshwater limestone formed by mineral deposits from natural sources. When first laid down, travertine forms a “very fine, muddy slime” that one can easily sink one’s hands and feet into, Bennett said. Then, once cut off from the water, the travertine hardens into stone.

On a previous expedition, conducted in the 1980s, Zhang discovered similar hands and footprints near a modern thermal bath in Quesang, and in general, many traces of early humans can be found gracing the slopes. near. These previously discovered hand and footprints vary in size, implying that they were left by children and adults alike, but they appear to have been made organically as people made their way through on the ground. The new footprints, on the other hand, differ in that they appear to have been left on purpose, Bennett said.

“They are deliberately placed… you won’t necessarily get these traces if you were doing normal activities on the other side of the slope,” he said. “They’re actually positioned in space, like somebody’s doing, you know, a more deliberate composition.” Bennett likened the prints to finger grooves – a kind of prehistoric art made by people running their fingers over soft surfaces on cave walls. Both children and adults are believed to have participated in the finger flute, and similarly, Bennett said Quesang’s engravings should be considered art as well.

Related: The 25 most mysterious archaeological finds on Earth

To compare to modern times, “I have a 3 year old daughter, and when she does a doodle, I put it on the fridge… and I say it’s art,” Bennett said. “I’m sure an art critic wouldn’t necessarily define my child’s scribbles as art, but in general we would [so]. And it’s no different. “

Work of art?

If the Quesang prints qualify as cave art, they would be the oldest known example of the genre ever discovered, the authors note in their report. Previously, the oldest known examples of cave art were patterns and hand stencils found on the Indonesian island of Sulawesi and in the El Castillo cave in Spain, both of which date from around 45,000 to 40,000 years ago.

Related: In photos: the oldest rock art in the world

However, “Quesang doesn’t have much to do with these two sites, other than the fact that all three of them display the hand [and] “Leaving an imprint in the mud or making a stencilled imprint with pigments is a really different process, not only from a technical point of view, but also from a conceptual point of view. ”

For Honoré, personally, cave art includes paintings and engravings made on rock, but would exclude marks like finger grooves or Quesang’s prints, and some other archaeologists are of the same opinion. “As far as fluting is concerned, some authors already consider it as art, others as precursors of art, others as’ experimentation. [or] play ‘rather than art, “Honore said.” I would personally be part of the latter category of researchers. “

“Classifying these human traces as art is something of only secondary importance, in my opinion,” Meyer said. The most interesting implications of the new study are that human ancestors occupied the Tibetan High Plateau much earlier than previously thought, and this raises questions about which hominid species left the footprints and how they did. arrived on the set for the first time. Looking ahead, Meyer said he hopes there will be further studies to verify the age of the prints and clarify how they have remained so well preserved over time.

Regardless of how contemporary scholars define prints, it is important to note that “what we define as art was probably not viewed in the same way by the people who made it,” said declared Honoré. So, we may never know what those former hominin children actually were doing when they stuck their hands and feet into the hillside, or what their older parents might have done with their efforts. For Bennett, however, the fossilized traces of two children playing in the mud still count as art in his book.

Originally posted on Live Science.

[ad_2]

Source link