[ad_1]

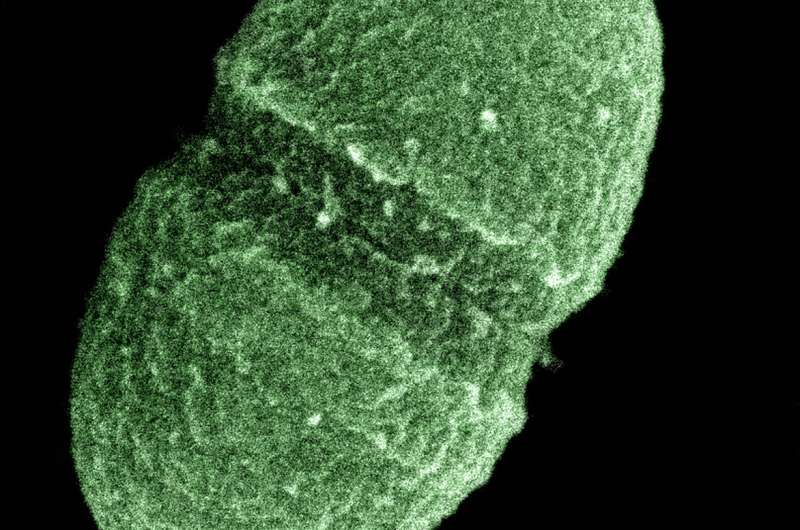

Enterococcus faecalis. Credit: United States Department of Agriculture / Public domain

Modern hospitals and antibiotic treatment alone have not created all of the antibiotic resistant strains of bacteria that we see today. Instead, selection pressures prior to widespread antibiotic use prompted some of them to thrive, new research has found.

Using analysis and sequencing technology that has only been developed in recent years, scientists at the Wellcome Sanger Institute, the University of Oslo and the University of Cambridge have created an evolutionary timeline of the bacteria, Enterococcus faecalis, which is a common bacteria that can cause resistance to antibiotics. infections in hospitals.

The results, published today in Nature communications show that this bacterium has the capacity to adapt very quickly to selection pressures, such as the use of chemicals in agriculture as well as the development of new drugs, which have caused the presence of different strains of the same bacterium in many places in the world, from the majority of people have guts to many wild birds. Since it is so prevalent, researchers suggest that people should be screened for this type of bacteria upon entering a hospital, in the same way they are for other superbugs, to help reduce the possibility. to develop and spread infection in healthcare.

Enterococcus faecalis is a common bacteria that most people find in the intestinal tract and do not harm the host. However, if a person is immunocompromised and this bacteria enters the bloodstream, it can cause a serious infection.

In hospitals, it is more common to find antibiotic resistant strains of E. Faecalis and it was initially believed that the widespread use of antibiotics and other antibacterial control measures in modern hospitals caused the development of these strains.

In a new study, scientists at the Wellcome Sanger Institute, the University of Oslo and the University of Cambridge analyzed around 2,000 samples of E. Faecalis from 1936 to the present using blood isolates from patients and stool samples from healthy animals and humans.

By sequencing the genome (including chromosomes and plasmids) using Oxford Nanopore technology, the team mapped the bacteria’s evolutionary journey and created a timeline of when and where different strains came to be. developed, including those that are now resistant to antibiotics. They found that antibiotic resistant strains developed earlier than previously thought, before the widespread use of antibiotics, and therefore, it was not just the use of antibiotics that caused their emergence.

Researchers have found that early agricultural and medical practices, such as the use of arsenic and mercury, influenced the evolution of some of the strains we are seeing today. On top of that, strains similar to the antibiotic resistant variants we now see in hospitals have been found in wild birds. This shows how adaptable and flexible this species of bacteria is to evolve into new strains in the face of different adversities.

Professor Jukka Corander, co-lead author and associate faculty member of the Wellcome Sanger Institute, said: “This is the first time that we have been able to map the complete evolution of E. Faecalis from samples up to 85 years old, which allows us to see the detailed effect of human lifestyles, agriculture and drugs on the development of different bacterial strains. Having the complete timeline of evolutionary changes would not have been possible without the analytical and sequencing techniques that can be found at the Sanger Institute. “

Dr Anna Pöntinen, co-lead author and postdoctoral researcher at the University of Oslo, said: “Currently, when patients are admitted to hospital, they are taken from certain antibiotic resistant bacteria and fungi and are isolated To ensure infection rates are Through this study, it is possible to scrutinize the diversity of E. faecalis and identify those that are more likely to spread in hospitals and therefore could harm immunocompromised people We believe that this could be of benefit for immunocompromised people also testing for E. faecalis on admission to hospitals.

Professor Julian Parkhill, co-author and professor in the Department of Veterinary Medicine at the University of Cambridge, said: “This research has found that these strains of antibiotic-resistant bacteria associated with hospital are much older than we are. pensions before, and demonstrated their incredible metabolic flexibility combined with numerous mechanisms improving their survival in difficult conditions which allowed them to spread widely throughout the world. ”

Antibiotic could be reused and added to TB treatment arsenal

Anna K. Pöntinen, Janetta Top and Sergio Arredondo-Alonso, et al. (2021) The apparent nosocomial adaptation of Enterococcus faecalis predates the modern hospital era, Nature communications (2021). DOI: 10.1038 / s41467-021-21749-5

Provided by Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute

Quote: Complete evolutionary journey of the hospital superbug mapped for the first time (2021, March 9) retrieved on March 9, 2021 from https://phys.org/news/2021-03-full-evolutionary-journey-hospital-superbug.html

This document is subject to copyright. Other than fair use for private study or research purposes, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for information only.

[ad_2]

Source link