[ad_1]

A coronavirus variant identified in South Africa may not be as vulnerable to COVID-19 vaccines as other strains, some scientists say.

Studies are currently underway to find out if this is really the case.

While the variant, known as 501.V2, is resistant to vaccines, the plans could be modified to increase their effectiveness – adjustments that would take about six weeks to make, vaccine developers told Reuters. These developers included BioNTech CEO Dr Uğur Şahin and John Bell, Regius Professor of Medicine at the University of Oxford, who are currently experimenting with the 501.V2 and the new coronavirus variant identified in UK, named B.1.1.7.

These experiments are so-called neutralizing tests – experiments in which they incubate viruses with antibody and human cells, to see if the antibody prevent infection, The Associated Press (AP) reported. They perform tests with blood from people who have been vaccinated and from those who have caught the virus and developed antibodies naturally, Dr Richard Lessells, an infectious disease expert who is working on South Africa’s genomic studies on 501.V2, told the AP.

Related: 20 of the worst epidemics and pandemics in history

In general, it is not surprising that variants like 501.V2 and B.1.1.7 have appeared; all viruses pick up mutations because they make copies of themselves, and the new coronavirus called SARS-CoV-2 is no exception. However, while the two recently identified variants share a few similar mutations, and 501.V2 “has a number of additional mutations … which are of concern,” Simon Clarke, associate professor of cellular microbiology at the University, told Reuters. from Reading.

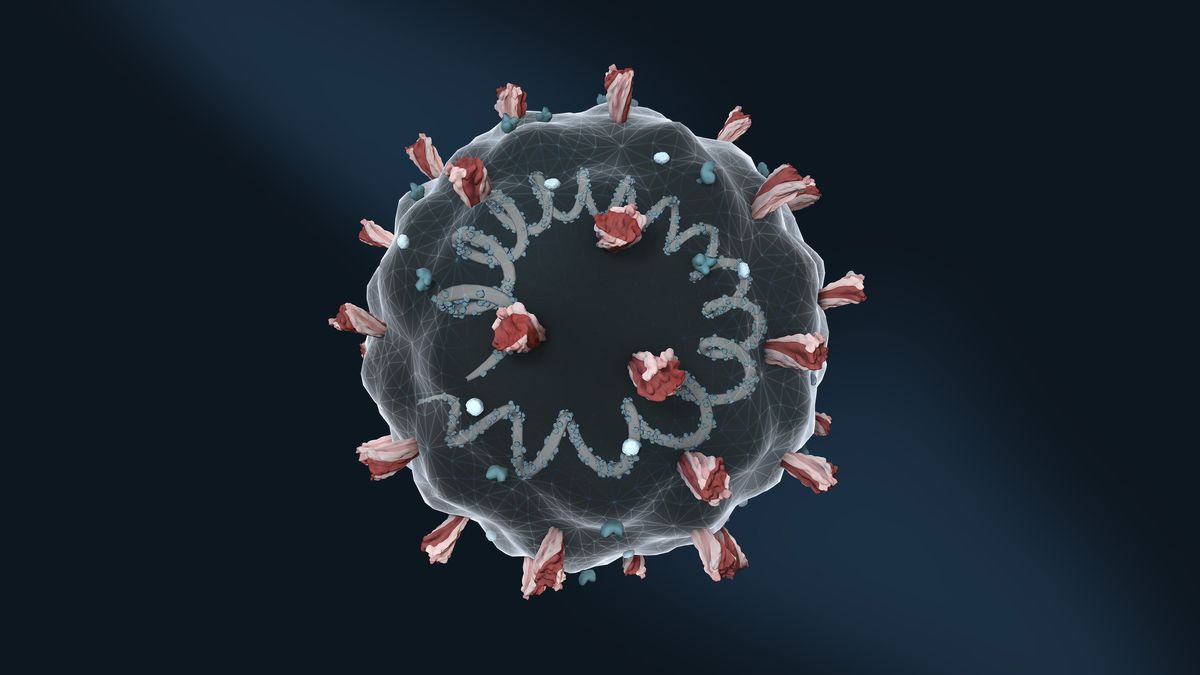

Specifically, the variant found in South Africa has more mutations in its spike protein – which protrudes from the surface of the virus and is used to invade human cells – than B.1.1.7, Lawrence Young, virologist and professor of molecular oncology at University of Warwick, told Reuters. Most of the vaccines available train the immune system to recognize this spike protein. If the spike protein accumulates too many mutations, it can become unrecognizable to the immune system, allowing the virus to bypass detection in the body; that’s the potential problem with the new 501.V2 variant, Young said.

That said, neutralizing tests should soon reveal whether or not we need to be concerned. As of now, Public Health England, an executive agency of the Department of Health and Welfare, said that there is currently no evidence to suggest that COVID-19 vaccines will not protect both B. 1.1.7 and 501.V2, Reuters reported.

In addition, several experts said The New York Times that it would likely take years, not months, for the coronavirus to mutate enough to bypass available vaccines.

“This will be a process that will occur on a timescale of several years and will require the accumulation of multiple viral mutations,” Jesse Bloom, evolutionary biologist at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle, told The Times. “It won’t be like an on-off switch,” in terms of how quickly the new variants become resistant to current vaccines, he said. In other words, vaccines can gradually become less effective over time, rather than suddenly not working.

Originally posted on Live Science.

[ad_2]

Source link