[ad_1]

Sometimes a vaccine is a slam dunk. Take the 97.5% effective Ebola vaccine, for example, or the 97% effective measles vaccine. Other times, a vaccine is a misfire, offering little or no protection, and clearly intended for trash.

Then there is a third group: the vaccines that are in the middle. They could protect some, but far from everything. The fate of these vaccines is less certain – an open question, in fact.

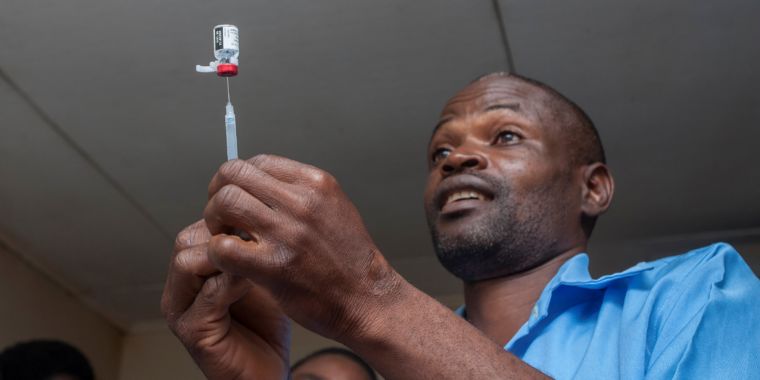

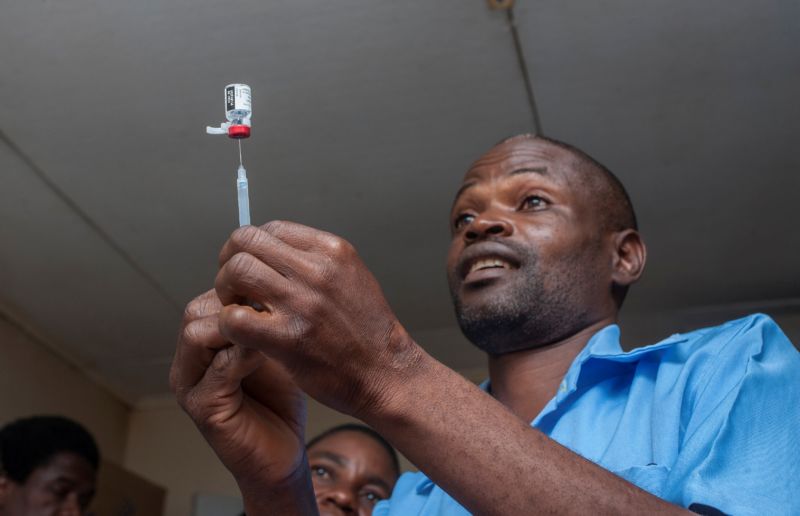

This is the case of the first global malaria vaccine, which was added on Tuesday with caution to routine vaccinations in the African nation of Malawi, as part of a pilot program. Ghana and Kenya will also introduce the vaccine in the coming weeks.

The vaccine, known as RTS, S, is effective in only about 39% of cases to prevent malaria – and this is only the case in children receiving four separate doses. It is effective only in 29% of cases to prevent the most serious forms of the disease transmitted by mosquitoes.

Nevertheless, with over 200 million cases of malaria worldwide each year and 435,000 deaths, even modest efficiency could save tens of thousands of lives.

"It's a defining moment," O'Brien told reporters at a news conference on Tuesday. She is Director of the Department of Immunization, Vaccines and Biologicals at the World Health Organization. RTS, S is a "vaccine of the first," she added. It is the first malaria vaccine to show such effectiveness after decades of research and dozens of other candidates. It is also the first to reach young vulnerable children as part of a routine immunization program.

RTS, S has been in the works for over 30 years. It was created in 1987 at GlaxoSmithKline and works by containing a fragment of a malaria parasite protein. Plasmodium falciparum. This fragment causes the immune system to attack after a mosquito has administered the parasite for the first time in the blood and before the parasite can infect the liver. This is where it can mature, reproduce and resuscitate to infect red blood cells and cause symptoms of the disease.

From 2009 to 2014, researchers tested RTS, S as part of a Phase III clinical trial conducted in seven African countries, where 250,000 children die each year from parasitic infection. Data collected from 15,500 infants and children during the trial showed that the effectiveness of the vaccine was only about 39%. It remains to be seen whether this efficiency rate will hold under real conditions.

Despite the high number of malaria victims and the absence of any other candidate vaccine on the horizon, public health experts have made the difficult call to recommend the deployment of RTS, S beyond testing – but they do with caution. The researchers will carefully monitor the pilot vaccination programs in the three countries, in which they will monitor the effectiveness, safety and ability of parents to bring their children with the four doses of vaccine. The results will guide policy decisions about whether the vaccine should be used elsewhere in the future.

"We think that it can be an additional tool – a flawed tool of modest efficiency – like all of our other malaria control tools – but that, when it does not work, it does not work. it is used imperfectly, may actually have a considerable impact, "Pedro Alonso, director of the WHO Global Malaria Control Program, said. Other tools used against malaria include indoor insecticide sprays, mosquito nets and improved screening and treatment of malaria.

"We are dealing with a very, very tough organization," said Dr. Alonso, speaking of the P. falciparum parasites that cause the disease. They are "really complex organisms," he said, and we do not know how long it will take researchers to design a better vaccine.

Pilot programs aim to reach around 360,000 children a year in all three countries. It should last five years. Public health experts will then evaluate the future of RTS, S.

[ad_2]

Source link