[ad_1]

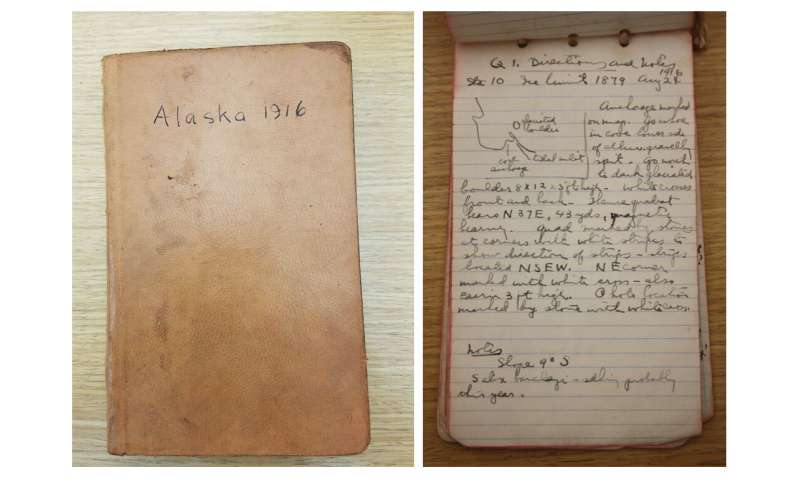

William S. Cooper's 1916 diary with a sketch of the entrance and directions to the first quadrilateral. In 2016, magnetic north had moved about 12 degrees and the entrance had dropped considerably. Credit: University of Colorado Denver

Ecologists have long been trying to understand and anticipate the changing composition of plant species, particularly now, as climate and land use disrupt the way plants colonize and develop their communities. Called succession of plants, the study of the prediction of plant communities through time is one of the oldest activities of ecology.

In 2016, Brian Buma, Ph.D., an adjunct professor of integrative biology at the University of Colorado Denver, assembled a team of researchers to hunt down and then expand eight long-forgotten, 103-year-old estate plots. a grant from National Geographic. The team discovered the parcels and, with the new data, relaunched the longest estate study in the world.

The researchers discovered that the initial random assortment of plants had spent a few decades fighting for dominance and sunlight, before settling into a stable and virtually immutable community for the next 50 years, thus upsetting the classic model of succession thinking.

The results were published in the journal Ecology.

Quadrats hunting

In 1916, William S. Cooper, one of the first presidents of the Ecological Society of America, measured six one-square-meter plots, called quadrats, located at the edge of a glacier in the park National Glacier Bay, Alaska, to study the development of an ecosystem. stripe. Cooper visited the quadrats every five to ten years until the 1940s, then his pupil took over the file until his death in 1988. Unfortunately, his student never published the results. Cooper's plots have been forgotten for more than 75 years. and buried in layers of soil and vegetation in the bush of Alaska.

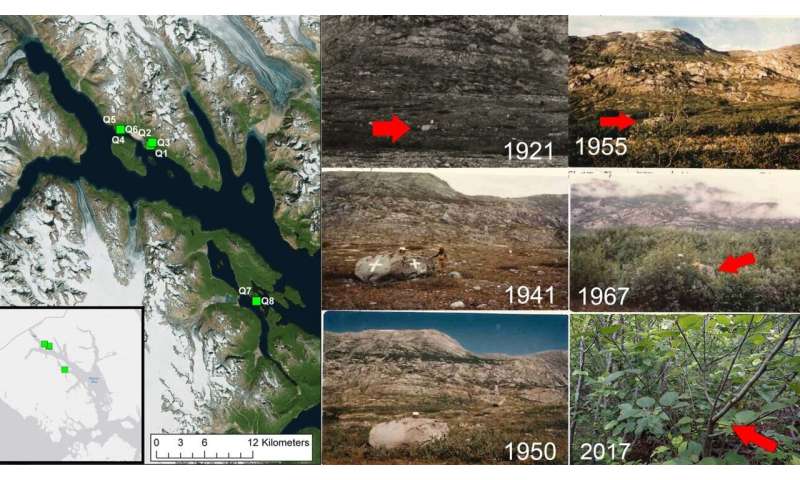

Cooper used a big rock as a reference point in his directions. In 2017, he was completely hidden and partially buried. Credit: University of Colorado Denver

Fortunately, the famous ecologist kept a detailed diary of his observations on life in the small quadrats, as well as maps and directions to follow them, but finding them would not be easy.

For starters, North of Cooper is not north of Buma. Since Cooper first listed the location of his plots of land, the magnetic pole of the Earth has moved about 12 degrees. Other landmarks have also changed: a wide cove has since been reduced to a small footprint on the shoreline, Cooper's open fields are now impassable and one of the quadrats is a victim of erosion and has fallen, literally, to the sea.

Cooper rammed steel nails or rebar bars to mark the corners and piled small rocky cairns around them to indicate their location. He marked the locations of the quadrats by surveying the distance between the large rocks, between 30 and 50 gaits, and varying degrees from the north. Notes such as "Go 12 steps from the big rock, 27 degrees north to a little cairn" were common.

Find 75 years of missing data

Armed with laminated photographs of plots and surrounding areas, Cooper's original handwritten diaries, a metal detector and a little luck, the researchers spent eight days searching for plots and finding the last in a few hours. Thanks to extensive fieldwork, historical records, remote sensing and dendrochronological methods, they have been able to complete data for the missing 75 years.

"Nowhere in the world can you look at data, maps and images dating back a hundred years ago and have the details necessary for this type of scientific study," Buma said.

Quadrat 2 in 1916 and 2016. Credit: University of Colorado Denver

Current chronosequence models

Until now, most ecologists have been relying on chronosequence studies to study long periods, during which researchers compared old sites to young sites as representatives of the passage of time. time to study the evolution of communities. But this suggests a huge assumption about the difference of these sites, as the old site may not have looked like the young site of a hundred years ago, Buma said.

As a result, chronosequence studies have yielded results predicting that plants interact with each other over time to form predictable successional trajectories. Cooper's quadrats in Glacier Bay show the opposite.

Instead of a succession of plants as suggested by the chronosequence models, 103-year-old communities remained relatively the same. No other plants have entered and existing plants have reproduced asexually.

"This undermines a lot of normal estate papers because it turns out that space is really important," Buma said. "There are a lot of random things that happen at the beginning of the plot story – where the seeds landed, for example – that still influence what we see today. 39 is like standing at the edge of a cliff and hitting a rock from the top.It falls, the rock can bounce back and forth and you can get hundreds of different paths, even if the rocks started more or less in the same place. "

In addition to monitoring Cooper's original quadrats, the Buma team has expanded plot sizes, added new basic biogeochemical data and spatial mapping for future researchers. Their goal is to observe if the conclusions of Cooper's plot reflect the wider reality now.

"The fields could all be similar in a thousand years," said Buma. "But at present, in the first hundred years, we can say that each is very different."

New artifacts suggest people arrived in North America earlier than expected

B. Buma et al. 100 years of primary succession have highlighted the stochasticity and competition, drivers of the establishment and stability of the community, Ecology (2019). DOI: 10.1002 / ecy.2885

Quote:

Ecologist revives the world's longest estate study (September 16, 2019)

recovered on September 17, 2019

at https://phys.org/news/2019-09-ecologist-revives-world-longest-succession.html

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair use for study or private research purposes, no

part may be reproduced without written permission. Content is provided for information only.

[ad_2]

Source link