[ad_1]

Frans von der Dunk, University of Nebraska-Lincoln

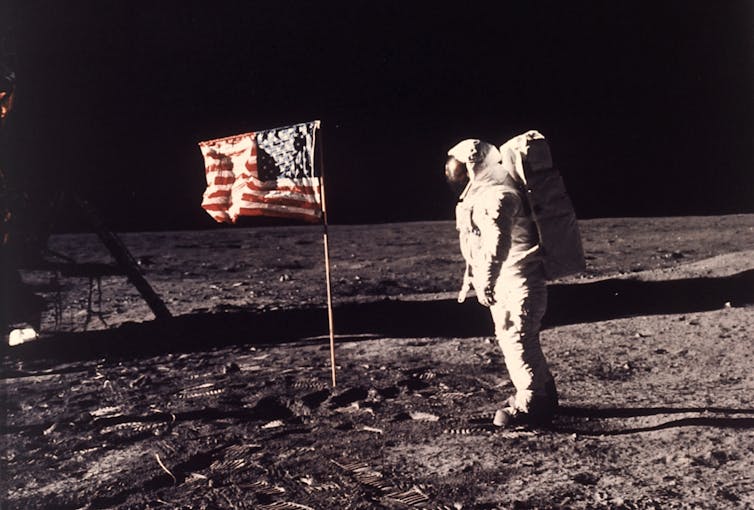

Most likely, it is the most well-known image of a flag ever taken: Buzz Aldrin standing next to the first American flag planted on the moon. For those who knew their world history, she also sounded the alarm. Less than a century ago, back on Earth, planting a national flag in another part of the world amounted to claiming that territory for the homeland. Did the Stars and Stripes on the moon mean the establishment of an American colony?

When people hear for the first time that I am a lawyer, I practice and teach what is called the "right of space". a big smile or a flicker in the eyes, it is: "So tell me, who owns the moon?"

Of course, claiming new national territories had been a European habit, applied to the non-European parts of the world. In particular, the Portuguese, Spanish, Dutch, French and English created enormous colonial empires. But while their attitude was very much centered on Europe, the legal idea that the planting of a flag was an act of sovereignty was quickly accepted and accepted around the world as an integral part of the right of people. in their minds only to contemplate the legal meaning and consequences of this flag planted, but fortunately the issue had been addressed before the mission. Since the start of the space race, the United States knew that for many people around the world, the presence of an American flag on the Moon would raise major political issues. Any suggestion that the moon could become, legally speaking, part of the backwaters of the United States could fuel these concerns, and possibly give rise to international disputes prejudicial to both the US space program and the American interests as a whole [19659007]. destroys any notion that the non-European parts of the world, although populated, were not civilized and therefore legitimately subject to European sovereignty – however, there was not a single person living on the moon; Yet the simple answer to the question of whether Armstrong and Aldrin, through their small ceremony, transformed the moon, or at least a large part of it, into American territory turns out to be "no". "Neither the United Kingdom, nor NASA, nor the United States government wanted the United States flag

The first treaty of space

More importantly, this answer was inscribed in the Space Treaty Outer Space of 1967, to which the United States and the Soviet Union as well as all other space countries had become party.The two superpowers agreed that the "colonization" of the Earth had been responsible for terrible human suffering and many armed conflicts that had raged over the past centuries, and they were determined not to repeat the error of the old European colonial powers when it came to deciding the legal status of the moon; least, the p The ossibility of "land grabbing" into space giving rise to a new world war was to be avoided. As a result, the moon became a kind of "global common" legally accessible to all countries – two years before the first effective landing of the moon.

Case closed , no need for specialized space lawyers? I do not need to prepare law students from the University of Nebraska-Lincoln space for postgraduate studies. other discussions and disputes over the lunar law, is not it?

No need for lawyers in the space? While the legal status of the Moon as "common good accessible to all countries in peaceful missions has not encountered any resistance or substantial challenge, the on the outer space left other details unresolved. Contrary to the very optimistic badumptions of the time, humanity has not returned to the moon since 1972, making the lunar land rights largely theoretical

C-It-Is say, until a few years ago when several new plans hatched to return to the moon. In addition, at least two US companies, Planetary Resources and Deep Space Industries, which have serious financial support, have begun targeting asteroids in order to exploit their mineral resources. Geek Note: As part of the above-mentioned Outer Space Treaty, the moon and other celestial bodies such as asteroids, legally speaking, belong to the same basket. None of them can become the "territory" of a sovereign state or another state.

The fundamental prohibition to acquire a new territory under the Outer Space Treaty by planting a flag or by any other means of natural resources on the moon and d & # 39; other celestial bodies. This is a major debate that is currently raging in the international community, without any unequivocal solution being in sight. Basically, there are two possible general interpretations:

So, you want to extract an asteroid?

Countries like the United States and Luxembourg (as a gateway to the European Union) agree that the moon and asteroids ", which means that Each country allows its private entrepreneurs, as long as they are duly authorized and in accordance with other relevant rules of space law, to go there and to do so. extract what they can to try to make money. It's a bit like the law of the high seas, which is not under the control of any particular country, but completely open to law-abiding and duly authorized fishing operations of the citizens and companies from any country. Then, once the fish is in their nets, it is up to them legally to sell

On the other hand, countries like Russia and a little less explicitly Brazil and Belgium maintain that the moon and asteroids belong to humanity as a whole. And as a result, the potential benefits of commercial exploitation should somehow increase for humanity as a whole – or at least should be subject to a probably stringent international regime to ensure benefits to the world. the scale of humanity. It's a bit like the scheme originally established for harvesting deep seabed mineral resources. Here, an international licensing regime was created as well as an international enterprise that exploited these resources and generally shared the benefits between all the countries

![]() Although in my Notice the old position more logical, both legally and practically, the legal battle is by no means over. Meanwhile, interest in the moon has also been renewed – at least, China, India and Japan have serious plans to return there, which further increases the stakes. Therefore, at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, we will have to teach our students these issues for many years to come. Although in the end it is up to the community of states to determine whether it is possible to reach a common agreement on either one of these two positions it It is crucial that an agreement can be reached in one way or another. Such activities developing without any generally applicable and accepted law would be a disaster scenario. Although no longer a colonization issue, it can all have the same adverse effects.

Although in my Notice the old position more logical, both legally and practically, the legal battle is by no means over. Meanwhile, interest in the moon has also been renewed – at least, China, India and Japan have serious plans to return there, which further increases the stakes. Therefore, at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, we will have to teach our students these issues for many years to come. Although in the end it is up to the community of states to determine whether it is possible to reach a common agreement on either one of these two positions it It is crucial that an agreement can be reached in one way or another. Such activities developing without any generally applicable and accepted law would be a disaster scenario. Although no longer a colonization issue, it can all have the same adverse effects.

Frans von der Dunk, Professor of Space Law, University of Nebraska-Lincoln

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Source link