[ad_1]

In the opinion of all, sleeping in space is a dream. After a long day of rigorous experiments and rigorous exercises, astronauts from the International Space Station retreat to their quilted sleeping nests, which have just enough room for the astronaut, a wall-mounted laptop, and a few artifacts practice. To avoid drifting through the station while catching zero zeros, the astronauts snuggle into a sleeping bag on the wall of their pod. As they begin to fall asleep, their bodies relax and their arms drift in front of them, making them look like floating zombies.

Pillows are missing from astronaut rooms. In microgravity, you do not need it – you do not even need to hold your head. Instead, it goes naturally from the front.

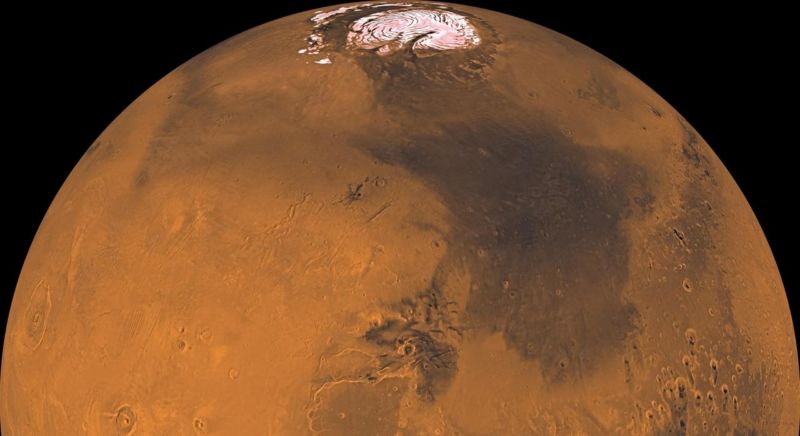

But just because the pillows are not necessary in space does not mean that astronauts should not have them. A pillow is the ultimate guarantee of comfort and well-being, a place to rest, to be vulnerable, to find peace. People bring their own pillows to hospitals to bring comfort to a cold clinic. So why not take one to the deepest of space? Future astronauts on long-term missions to Mars, which are expected to last at least 1,000 days according to NASA, may well wish for a reminder of life on their planet.

These are considerations such as those that keep Tibor Balint awake at night, so to speak. As NASA 's leading human – powered designer of NASA' s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Balint spends its time searching for ways to integrate the principles of art and design into project – based projects. human space. Now that we are on the point, because of the deadlines imposed by the space mission, to send a human to Mars, Balint thinks mission architects must begin to meet the higher psychological needs of astronauts. Enter the space pillow, or as Balint calls it, the space pillow system.

As detailed in an article recently published in Acta AstronauticaBalint and his colleague Chang Hee Lee, an assistant professor at the Royal College of Art, sought to create an object that would bring comfort, reduce stress and enhance the privacy of astronauts during a multi-year mission on the Red Planet. The pair finally landed on the pillow as an ideal "ideal" object, at the crossroads of various disciplines and could spark conversations about other aspects of life in space. So, while astronauts may not need a pillow to sleep in space, Baliant explains that designing a headrest has allowed them to consider what travelers space would need beyond the basics of maintaining life.

For the entire history of space exploration, astronauts have never been that until three days of the Earth. Whether on the ISS or on the surface of the moon, they could maintain constant radio contact and, perhaps more important from a psychological point of view, see their planet of origin. For astronauts during the first mission on Mars, the situation will be remarkably different. Radio communication will be delayed by up to 20 minutes. When astronauts look out the windows of their spaceship, they will not see the sunrise on a blue ball, but the darkness of the space. And rather than having a daily schedule scheduled to the minute, they will have plenty of time off on their commute – a time that could wreak havoc on those who are unprepared.

"In a way, you're in solitary confinement for three years," says Balint. "That's why we need to start looking at these higher level needs because without them, people will go insane."

"Merchandise, firmness and pleasure"

Balint refers to what is called Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs, a famous but controversial framework for understanding human motivation. According to psychologist Abraham Maslow, once a person's basic needs (food, housing, security) are met, the person is motivated to meet higher-level needs, namely friendship, intimacy and creative possibilities. According to Maslow's theory, meeting these larger needs is the key to psychological well-being.

Maslow was not the first to try to understand basic needs; the act itself is in a way a human pastime that goes back several centuries. More than 2,000 years ago, the master Roman architect Vitruvius applied this type of thinking to architecture by making "convenience, firmness and pleasure" the three essential qualities of buildings intended for the 39, human habitation. The last 50 years of human-rated spacecraft have excelled in the first two qualities, being both structurally sound and effectively exploiting space. In the opinion of Balint, what is missing, it is the pleasure of Vitruvius.

It's where the pillow of space comes in. To overcome isolation and monotony, astronauts will need various stimulating ways to interact with their surroundings. As Balint and Lee have quickly discovered, the options for a "human-material interaction" in pillow design are vast. They could focus on physiological considerations and design the pillow as a neck brace. They could also satisfy the senses of astronauts by soaking the pillow with soothing smells. Perhaps they could install sensors and speakers in the pillow to detect when an astronaut fell asleep and play relaxing music. Alternatively, they could make the pillow interactive, like an Amazon Echo, by turning the cushion into a sort of astro-Wilson for future martian castaways.

Balint and Lee designed a series of space pillows, each designed to meet all or part of the higher level needs they had identified for astronauts. These models included integral hoods with visors, headphones or a variable-light neck support; an inflatable pillow "space angel" worn as a halo that gives off relaxing aromas; and a semi-rigid helmet that would be physically attached to the wall of the sleeping pod of an astronaut. In the end, Balint and Lee decided that the pillow helmets seemed rather uncomfortable and could pose security problems to NASA.

"Seamless"

The design of the pillow they chose looks a lot like a conventional pillow. In the model published in their article, a shallow foam cushion is attached to the wall of an astronaut's sleep station. While Balint recognized the similarity of this design with what already exists on the ISS, he emphasized the "transparent" relationship of the pillow with other objects in the neighborhoods of the city. astronaut. These can include aromatic devices, speakers or relaxing light screens, all of which can be connected to the pillow through small sensors. Rather than integrating loudspeakers and screens into the cushion itself, the object is rather a "decoupled space pillow system" integrated into a network of external objects. Sensors in the pillow could detect when an astronaut would fall asleep, for example, and the lights of the pod would adjust accordingly. Think of this space pillow as a node in a smart home that can turn on lights, adjust the temperature, and so on. according to the movements of a person.

At the moment, Balint and Lee's pillow remains purely conceptual and it's exactly what they want. Discussions about the texture, color or softness of the pillow are secondary considerations, says Balint. The important thing in the space pillow is that it can serve as an anchor point for discussions about the psychological well-being of astronauts. As space-habitat design is gaining ground, Balint hopes that its space pillow will remind engineers that artists and designers also need to be part of the conversation.

This story originally appeared on wired.com.

[ad_2]

Source link