[ad_1]

As winter looms and hospitals across the United States continue to be inundated with severe cases of COVID-19, flu season presents a particularly disturbing threat this year.

We are researchers specializing in vaccination policies and the mathematical modeling of infectious diseases. Our group, the Public Health Dynamics Laboratory at the University of Pittsburgh, has been modeling influenza for over a decade.

One of us was a member of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Immunization Practices Advisory Committee and the CDC’s Flu Vaccine Effectiveness Network.

Our recent modeling work suggests that last year’s slow flu season could lead to an increase in flu cases this coming season.

Anti-COVID-19 strategies have also reduced influenza

Following the many measures put in place in 2020 to curb the transmission of COVID-19 – including restricting travel, wearing masks, social distancing, closing schools and other strategies – the United States have seen a dramatic decrease in influenza and other infectious diseases during the past flu season.

Childhood influenza-related deaths have increased from nearly 200 in the 2019-20 season to one in the 2020-2021 season. Overall, the 2020-2021 influenza season saw one of the lowest numbers of cases in recent U.S. history.

While reducing the flu is a good thing, it could mean that the flu will hit harder than normal this winter. This is because a large part of the natural immunity that people develop against the disease comes from the spread of this disease through a population.

Many other respiratory viruses have seen a similar decline during the pandemic, and some of them, including the interseasonal respiratory syncytial virus, or RSV, have increased dramatically as schools reopened and social distancing, masking and other measures have declined.

Decryption of viral transmission

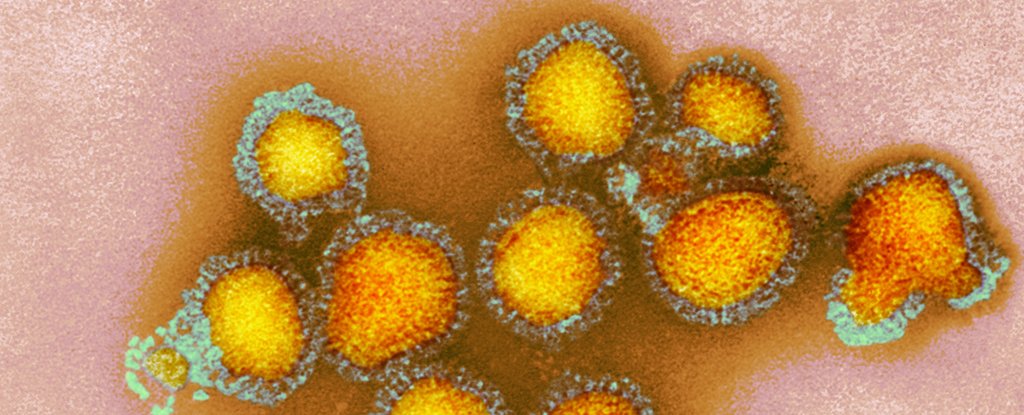

Immunity against influenza involves multiple factors. Influenza is caused by several strains of an RNA virus that mutate at different rates each year, in a manner similar to mutations that occur in SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19.

A person’s level of immunity to the flu strain in the current year depends on several variables. They show how similar the current strain is to what a child was first exposed to, whether the circulating strains are similar to previously experienced strains, and how recent these influenza infections were, if they have occurred.

And of course, human interactions, such as children crowding into classrooms or people attending large gatherings – as well as the use of protective measures like wearing a mask – all affect transmission. of a virus between people.

There are also variables due to vaccination. The immunity of the population to vaccination depends on the proportion of people who receive the influenza vaccine in a given season and the effectiveness – or adequacy – of that vaccine against circulating influenza strains. .

No precedent exists for a ‘twindemia’

Given the limited spread of influenza in the general United States population last year, our research suggests that the United States may experience a large influenza epidemic this season. Coupled with the existing threat of the highly infectious delta variant, this could lead to a dangerous combination of infectious diseases or ‘twindemia’.

Models of COVID-19 and other infectious diseases have been at the forefront of predictions for the COVID-19 pandemic and have often been shown to predict cases, hospitalizations and deaths.

But there are no historical examples of this type of double and simultaneous epidemics. As a result, traditional epidemiological and statistical methods are not well suited to projecting what may happen this season. Therefore, models that incorporate the mechanisms of a virus’ spread are better able to make predictions.

We used two separate methods to predict the potential impact of last year’s decline in influenza cases on the current 2021-2022 influenza season.

In our recent research which has not yet been peer reviewed, we applied a modeling system that simulates the interactions of a real population at home and at work, as well as at school and in the neighborhood. . This model predicts that the United States could see a sharp increase in influenza cases this season.

In another preliminary study, we used a traditional infectious disease modeling tool that divides the population into people susceptible to infection, infected people, recovered people, and people hospitalized or deceased.

Based on our mathematical model, we predict that the United States could see as many as 102,000 additional hospitalizations above the hundreds of thousands that typically occur during flu season.

These figures assume that there is no change from the usual use and effectiveness of the influenza vaccine starting this fall and throughout influenza season.

Individual behaviors and vaccination matter

A typical influenza season typically produces 30 to 40 million cases of symptomatic illness, between 400,000 and 800,000 hospitalizations, and 20,000 to 50,000 deaths.

This prospect, coupled with the ongoing battle against COVID-19, raises the possibility of a twinning crushing the healthcare system as hospitals and intensive care units in parts of the country overflow with critically ill COVID-19 patients.

Our research also highlighted how particularly young children could be at risk, as they are less exposed to previous flu seasons and therefore have yet to develop broad immunity compared to adults. In addition to the burden on children, childhood flu is a major contributor to influenza in older people as children pass it on to their grandparents and other older people.

However, there is cause for optimism, as people’s behaviors can dramatically alter these results.

For example, our simulation study incorporated people of all ages and found that an increase in vaccination in children has the potential to halve infections in children. And we’ve found that if just 25% more people than usual get the flu shot this year, that would be enough to bring the infection rate back to normal seasonal flu levels.

In the United States, there is great variability in vaccination rates, adherence to social distancing recommendations, and mask wearing. It is therefore likely that the flu season will see substantial variation from state to state, just as we have seen with the patterns of COVID-19 infection.

All of this data suggests that while influenza vaccination is important every year, it is of the utmost importance this year to prevent a dramatic increase in influenza cases and to prevent American hospitals from being overwhelmed. ![]()

Mark S Roberts, Professor Emeritus of Health Policy and Management, University of Pittsburgh and Richard K Zimmerman, Professor of Family Medicine, University of Pittsburgh.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

[ad_2]

Source link