[ad_1]

Brigitte Schoenemann

Among the fossils, the trilobites are rock stars. They’re adorable (as stony arthropods do), with a segmented shape distinctive enough to be a common logo. But they’re also fascinating because there are so many examples in the fossil record over such a long period of time, given that they have thrived for over 250 million years. The study of their evolution is enlightening in part because the chances are good to find excellent specimens.

Brigitte Schoenemann from the University of Cologne and Euan Clarkson from the University of Edinburgh took a peek into the eyes of a perfectly preserved trilobite specimen, and they learned a lot about how the eyes of the creature developed and what that says about evolution. And, as a bonus, they conclude that this particular species of trilobite was likely translucent.

A real goal

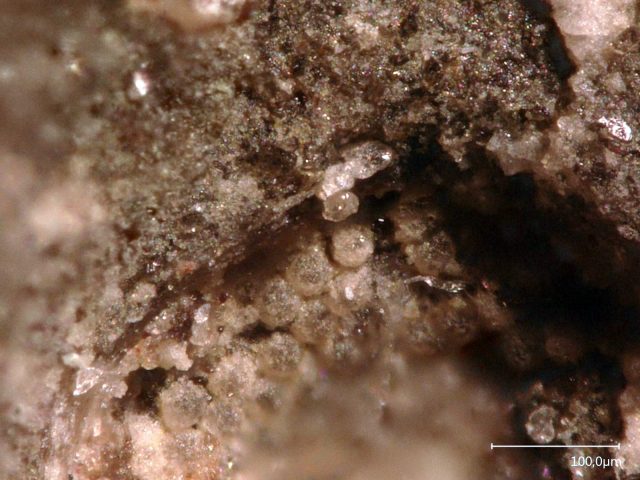

The fossil in question comes from sedimentary rocks 429 million years old in the Czech Republic. It is a one centimeter long trilobite called Aulacopleura koninckii which split in half when the rock layer was peeled off. The shape of the structures in one of its two eyes is clearly visible, with pieces distributed between the two halves.

Like other primitive arthropods, trilobites had compound eyes – think of the multifaceted cluster of a fly’s eye. Each unit in this cluster is called an “ommatidium”. At the top of each ommatidium is a lens, with conical cells underneath that also help focus incoming light. This light is carried through a rod-shaped “rhabdom” to reach the receptor cells which send signals to the brain. The researchers were able to distinguish each of these components in the fossil.

Brigitte Schoenemann

Some of the details of these structures have been debated for trilobites, as it’s not every day you come across a fossil that preserves them. Most notably, the makeup of the pair of lenses and cones is a bit hazy, with questions as to whether the trilobites formed useful lenses using the mineral calcite, as some organisms do today. These researchers discovered an older trilobite eye (over 500 million years ago) a few years ago and noted a lean lens without calcite that left the work of refraction on sturdy cone cells.

This trilobite eye is different. The cone looks tiny, while the lens is considerably thicker. Even a thicker chitin lens isn’t refractive enough to focus light underwater, but it would be up to the task with calcite inside. Researchers suspect this is the case here.

Magnificent isolation

Another interesting observation concerns what is surroundings this whole structure. In this kind of compound eye, each ommatidium must be enclosed in something that blocks light in order to isolate it from neighboring ommatidia, keeping each unit separate. Structural walls can be seen fulfilling this job in the fossil specimen, but researchers are also seeing signs of dark pigment in these walls. (Incredibly, these pigments are stable enough to be preserved in fossils.) It seems duplicative, but modern translucent creatures like shrimp also have pigments in these walls, as the walls themselves are not enough to block light. . Thus, the researchers suggest that these trilobites could also have been translucent.

Brigitte Schoenemann

Global, all about this compound eye looks modern – “comparable to that of living bees, dragonflies and many diurnal [daylight-dwelling] Crustaceans, ”the researchers write. It would show how far this system evolved a long time ago.

Given the length / width proportions of the lenses and ommatidia in the fossil, researchers can also use analogies with modern organisms to guess the habitat of the trilobite. He likely lived in shallow, well-lit water and was active during the day, they say. So if you could travel 429 million years back, this is where you would start looking A. koninckii, rushing like a flattened glassy shrimp.

Scientific reports, 2020. DOI: 10.1038 / s41598-020-69219-0 (About DOIs).

[ad_2]

Source link