[ad_1]

For some people with difficult-to-treat depression, a personalized device implanted for the brain may provide relief when nothing else can, suggests a new case study published on Monday. Researchers claim, for the first time, to have used tailor-made deep brain stimulation to significantly relieve a patient’s severe depression that has lasted for decades. While there are many questions about the feasibility of this large-scale technology, they hope it could prove to be an incredible breakthrough in the field.

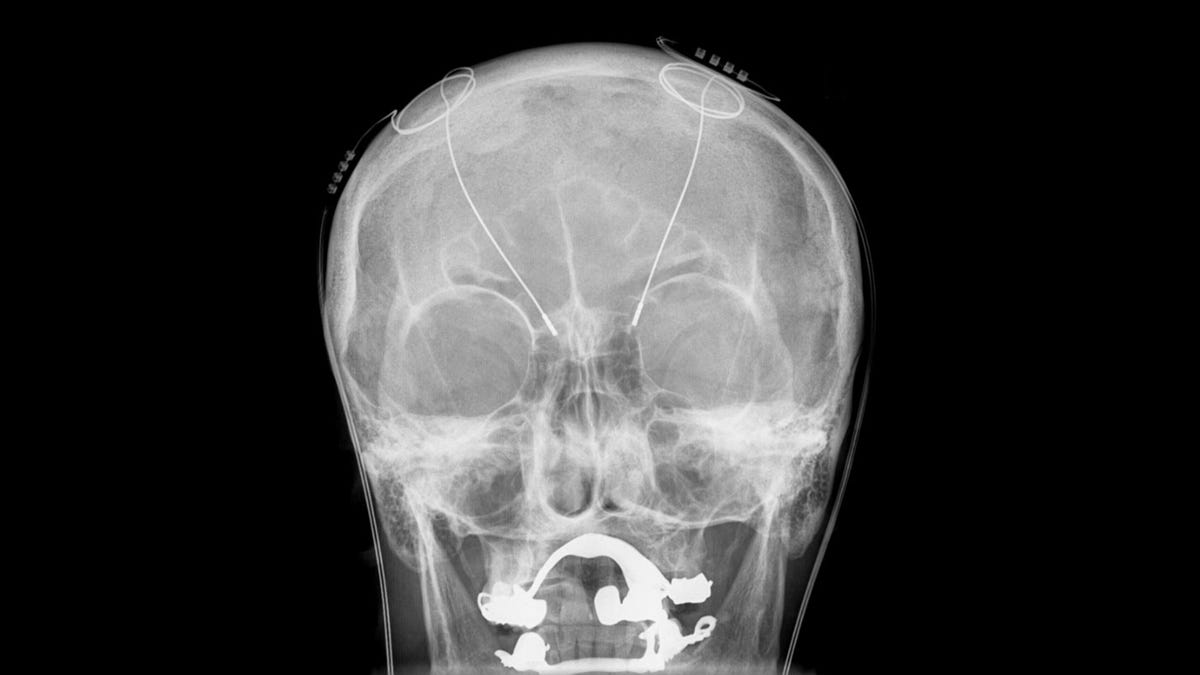

Deep Brain Stimulation, or DBS, is already used successfully to help manage neurological conditions, including Parkinson’s disease and certain types of seizures. The concept behind DBS is to transmit electrical impulses to balance the erratic patterns of brain activity associated with the target condition, hopefully eliminating or reducing the person’s symptoms. These impulses are sent through electrodes implanted in the brain, regulated by a device usually implanted elsewhere in the body, much like the operation of a pacemaker.

DBS for depression has been a mature area of study, as there appear to be notable differences between the brains of people diagnosed with depression and those who are not. But so far, the evidence for its benefits has been inconsistent, with patients varying in responses. In recent years, scientists at the University of California at San Francisco have been working on ways to improve DBS, for example by discovery possibly more relevant areas of the depressed brain to stimulate. Based on this previous research, they developed their own unique DBS technique, which they call personalized closed-loop neurostimulation.

In a new study published Monday in Nature Medicine, they detail how their method appears to have been successful in treating a 36-year-old woman who suffered from depression since childhood. And at a press conference held late last week, the patient herself, identified as Sarah, testified to the almost instant relief she felt after starting treatment.

“When I first received the stimulation, the ‘aha’ moment came, I felt the most intensely happy feeling, and my depression was a distant nightmare for a while,” said Sarah, whose the depression had become more severe in recent years, to the point where she had constant thoughts of suicide. “The expression made me realize that my depression was not a moral flaw. It was a treatable disorder and there was hope for my recovery.

G / O Media may earn a commission

The method is said to work by first finding the specific brain activity patterns associated with a patient’s depressive state, and then fine-tuning the impulses needed to counter them. Once this is established, the patient is equipped with a device capable of detecting the onset of these moments of erratic brain activity and automatically sending stimulation to the brain. This contrasts with typical DBS, which involves sending pulses all the time or at fixed intervals throughout the day, such as before bed. In Sarah’s case, dysfunctional brain activity involved the ventral striatum, a crucial player in decision-making, as well as the amygdala, an important regulator of our emotional response, especially fear and anxiety.

The authors warn that this is only a unique case and that Sarah’s experience should only be seen as a proof of concept. More research will be needed to see if this treatment can be successfully replicated. While it may be the case, Sarah’s treatment took a lot of time and resources to calibrate – efforts that will make it difficult to make this technology available to patients with depression at this time. Although the device itself is commercially available, the treatment would likely be expensive, with researchers estimating a cost of around $ 30,000, based on existing costs for DBS.

“For this to help more people, it’s going to need some simplification,” said Edward Chang, study author and researcher at UCSF, in response to a question from Gizmodo about the long-term future of this treatment. . “But we also see plenty of opportunities to think about how technology, for example, can be used to help and minimize or reduce the amount of manual labor and manpower required to perform those truly comprehensive analyzes that were part of this essay. “

Study author and UCSF researcher Katherine Scangos said her team’s discoveries could pay off in other ways, even before the technology can be scaled up.

“We have identified, through this test, some fundamental properties of the brain, namely that the brain is understandable, that the organization and function of the brain can be reliably identified,” said Scangos. “And so we believe these findings about the brain will be made available to the general public and will help us develop new personalized treatments for depression, with a focus on brain circuits.”

Colleagues at Scangos are already studying whether it is possible to non-invasively stimulate brain circuits specifically associated with a person’s depression, she added.

As for Sarah, her symptoms of depression started to reappear between the first sessions of stimulation and the implantation of the perm. device. But once he was implanted and turned on, Sarah once again felt immense and continuing relief – enough to finally apply the skills she had learned in therapy earlier, she said. Now, a year after starting treatment, she added, her depression remains at bay and she feels able to “rebuild a life worth living”.

Following: DARPA’s brain chip implants could be the next big breakthrough in mental health, if not total disaster

[ad_2]

Source link