[ad_1]

The 32-year-old went into hiding after the Taliban took control of Afghanistan in August, cutting off communication with his family at home and taking refuge in a Kabul basement with his younger brother. They spent their days reading, praying and venturing outside just for food.

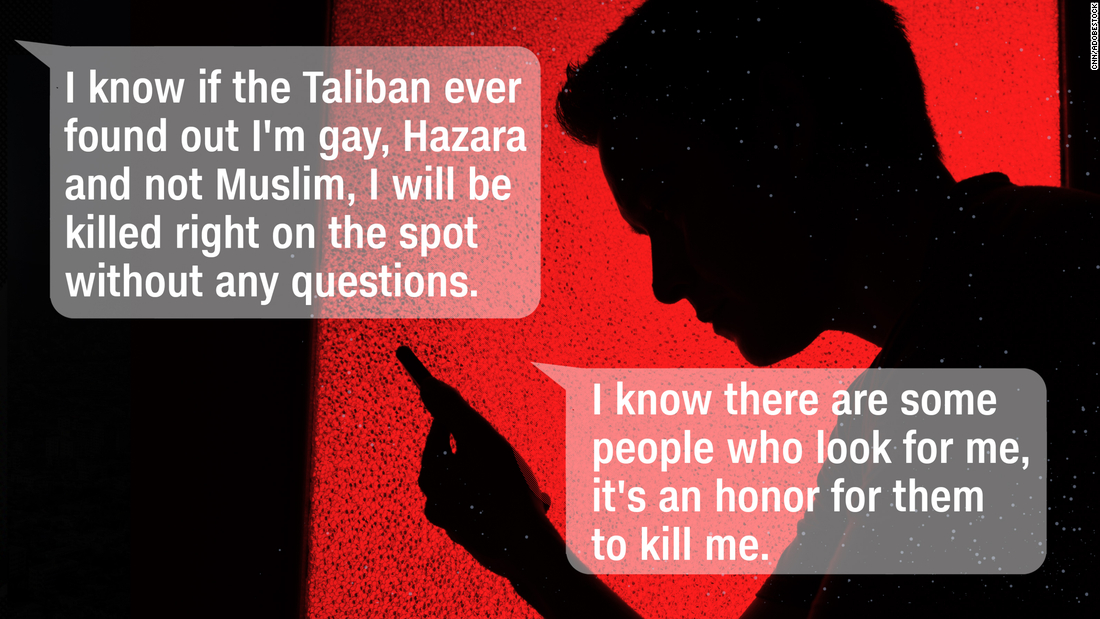

With phones as the only connection to the outside world, he and his brother sent messages. Lots of messages. To human rights activists and organizations. To friends of friends who knew someone who could help.

Their greatest fear: meeting a doom at the hands of the Taliban, as their father did years ago.

“They will behead or kill us in the most brutal way,” the older brother told CNN. “They are masters in this.

CNN has verified the man’s identity through human rights activists and messaged him via WhatsApp since August. To protect his safety, CNN only identifies him as Ahmed – not his real name.

The days in the basement turned into weeks filled with terror and isolation. Sometimes Ahmed felt so desperate that he contemplated suicide.

Then, at the end of last month, word of a possible escape route came.

In a series of recent WhatsApp messages, Ahmed recounted his life in the shadows in Kabul, his deep-rooted fear of the Taliban and his race to flee a country where he has lived his entire life.

He first fled to Kabul for his safety

It was early August. The newly emboldened Taliban were taking control of cities across Afghanistan, and Ahmed could smell terror in the air.

He began to fear that someone in the northwestern town of Mazar-i-Sharif, where he and his brother lived, would hand him over to the Taliban.

So on August 12, the siblings hastily packed their bags and took a bus to Kabul.

Ahmed felt he would be safer as a gay man in the sprawling Afghan capital. But three days after their arrival, Kabul fell into the hands of the Taliban.

Ahmed was well aware of the Taliban’s treatment of minorities in Afghanistan.

He tried to hide his features in public

Many Hazaras have features from Central and East Asia – a lighter skin color and distinctive shaped eyes – that set them apart from most Afghans. The ethnic group largely practices Shiite Islam.

Ahmed therefore wore traditional clothes and a turban. A medical mask covered his sparse facial hair. Sunglasses obscured his eyes – and all eye contact with Taliban soldiers.

But at first he wasn’t always careful. One day in August, he was arrested by the Taliban for wearing a baseball cap. They pulled him out of his head and asked why he was wearing a “hip hop” hat, he said.

The brothers tried to avoid public places. They hid in a small room in an alley in a densely populated area of Kabul, where they slept on the floor with the windows covered.

Whenever they heard noises outside, Ahmed would say “we would sit in the dark, totally still, afraid to move a muscle”.

Michael Failla, a Seattle-based human rights activist who helped the brothers, said he received panicked calls from Ahmed in the middle of the night.

“There was a time when he called me sobbing and told me that he heard that the Taliban were door-to-door in the neighborhood,” Failla said.

“He threatened to jump out of a building because he thought it would be a less painful way to die than to be caught and beheaded by the Taliban as a gay man.

The fear he and his brother have of the Taliban is personal

The fear of the Taliban brothers is rooted in their family history.

The Taliban threw his father in the back of a van and left, he said. It was the last time he had seen her. Ahmed was 9 years old.

Even before their father died, Ahmed said his childhood was far from idyllic. He recalls good times spent cycling under a pomegranate tree, but also brutal attacks on the Hazaras and the LGBTQ community in his town.

And he said the chaos following the recent Taliban takeover brought back painful memories.

Ahmed’s younger brother is 26 and not gay. But as a Hazara and a Christian, he was also in danger in Afghanistan.

Eight years ago, they lost their mother to a brain tumor. Since then, orphans, who have no other siblings, have always faced the world together.

Activists rushed to get them out of the country

It is not known how many LGBTQ people are in Afghanistan, as most of them live in the shadows, activists say.

Since the country fell to the Taliban, human rights groups have worked to get LGBTQ Afghans out of the country.

With the help of donors, Project Aman sent money to LGBTQ people in Afghanistan and advised them to stay in hiding until they could gain asylum in other countries.

Seattle activist Failla has also helped LGBTQ Afghans like Ahmed flee persecution.

“The Taliban say they will be easier on women and minorities. But no one is saying they will be easier on the LGBTQ community,” Failla said, calling them “the most vulnerable minority in the country.”

The day that changed everything

Ahmed downloaded an app that deleted his messages once they were read. He wanted to be ready in case the Taliban seized his phone.

He was in agony. And he waited.

Then, one day in late September, he received a call from an activist. A flight was available in the next few days to transport him and his brother to Pakistan.

Ahmed was ecstatic but fearful. As the day of departure approached, he became obsessed with how he would pass Taliban checkpoints.

On the day of the flight, he put on his traditional dress. He had already grown his beard to hide his face. Ahmed took a deep breath and walked with his brother to the airport.

Now he’s safer. But his journey is far from over

Today in Islamabad, Ahmed is cautiously optimistic. He spends most of his days reading and walking around his new neighborhood.

“We are relieved to have them there temporarily,” Failla said. “They were in extreme danger (in Kabul). It’s almost like a genocide that they (the Taliban) committed with the Hazaras.”

Meanwhile, Ahmed tries to get used to his new surroundings. Although Pakistan is not a role model for LGBTQ rights, he says he and his brother feel much safer there. Their ordeal is mostly behind them.

And he finally dares to hope for his future.

[ad_2]

Source link