[ad_1]

Asteroids and comets both orbit the sun, but asteroids are made up of metals and rocky material, while comets are made up of different types of ice, rock, and dust. When their orbits move comets closer to the sun, they heat up. These frozen objects on the edge of the solar system release dust and rocks as their ice vaporizes, creating characteristic tails that can stretch for millions of miles.

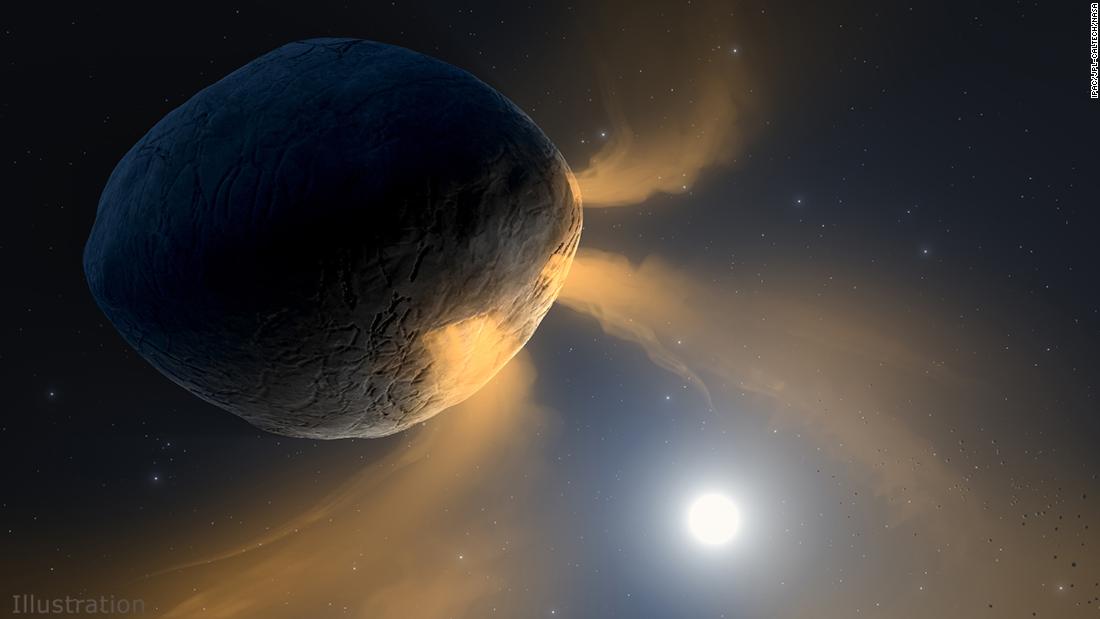

Comets and their icy debris are usually responsible for the meteor showers we see in the night sky, which makes Phaethon unusual. Scientists have debated the very nature of what Phaethon is. The closely followed near-Earth asteroid has been compared to comets, so it has been called a “rock comet.”

Phaethon was discovered in October 1983 and named after the Greek myth about the son of Helios, the sun god, as he came close to our sun.

So why does the 5.8 kilometers wide (5.8 kilometers wide) asteroid Phaethon light up as it approaches the sun? New modeling and lab tests have revealed that the asteroid may reject something else when it warms up: sodium.

“Phaethon is a curious object that becomes active as it approaches the Sun,” said lead author of the study, Joseph Masiero, a scientist at the California Institute of Technology’s Center for Infrared Processing and Analysis. , in a press release.

“We know it’s an asteroid and the source of Geminids. But it contains little or no ice, so we were intrigued by the possibility that sodium, which is relatively abundant in asteroids, could be the driving force. of this activity. “

At its closest point to the sun, Phaethon’s surface temperature rises so much that the sodium inside the asteroid sparkles, vaporizes, and escapes into space. This would make the asteroid glow, almost at the level of a comet, and also spread rocky debris.

Secrets in the meteor shower

Before meteorites, or small pieces of rocky debris from outer space, burn in our atmosphere, they literally light up their makeup. This debris heats up to thousands of degrees before decaying, creating light. And the color of that light can reveal the elements found in a comet, or in this case, an asteroid.

Sodium creates an orange light, not something seen much in the Geminid meteor shower. But if the sodium vaporizes out of the asteroid and ejects meteorites from the asteroid’s surface, there wouldn’t be much sodium left.

“Asteroids like Phaethon have very low gravity, so it doesn’t take a lot of force to push debris off the surface or dislodge rock from a fracture,” said study co-author Björn Davidsson, scientist. at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California. , in a report. “Our models suggest that very small amounts of sodium is all that’s needed to do this – nothing explosive, like steam erupting from the surface of an icy comet; it’s more of a constant fizz.”

To test this idea, the researchers analyzed samples from the Allende meteorite that fell in Mexico in 1969. These samples were interesting because it is likely that the meteorites came from an asteroid like Phaethon. Samples of Allende have been heated to the same temperatures Phaethon faces when he is closest to the sun.

“This temperature is around the point where sodium escapes from its rock components,” study co-author Yang Liu, a JPL scientist, said in a statement. “So we simulated this heating effect over the course of a ‘day’ on Phaethon – his three hour rotation period – and, comparing the minerals in the samples before and after our lab tests, sodium was lost, while the other elements have been left out. This suggests that the same can happen on Phaethon and seems to be in agreement with the results of our models. “

The findings add to a scientific conversation about the nature of asteroids and comets.

“Our latest finding is that if the conditions are right, sodium can explain the nature of some active asteroids, making the spectrum between asteroids and comets even more complex than we previously thought,” Masiero said.

[ad_2]

Source link