[ad_1]

Scientists have discovered two new lakes buried deep beneath the Antarctic Ice cap.

These hidden gems of freezing water are part of a vast network of ever-changing lakes hidden under 1.2-2.5 miles (2-4 kilometers) of ice on the southernmost continent. These lakes fill and empty again and again in largely mysterious cycles that can influence the speed at which the ice sheet moves and how and where the meltwater reaches the Southern Ocean. This flow, in turn, can alter currents in the Southern Ocean and potentially affect ocean circulation around the world.

“It’s not just the ice cap we’re talking about,” said Matthew Siegfried, study leader, geophysicist at the Colorado School of Mines, said in a press release. “We are really talking about a water system that is connected to the entire Earth system.”

Related: Photos of Antarctica: the bottom of the world covered in ice

Hidden water

The lakes lie at the bottom of the ice cap, where the ice meets the rocky Antarctic continent. Contrary to Greenland, where meltwater drains from the ice surface through crevices and holes called mills, Antarctic lakes form under the ice, presumably due to pressure, friction and can -be geothermal heat.

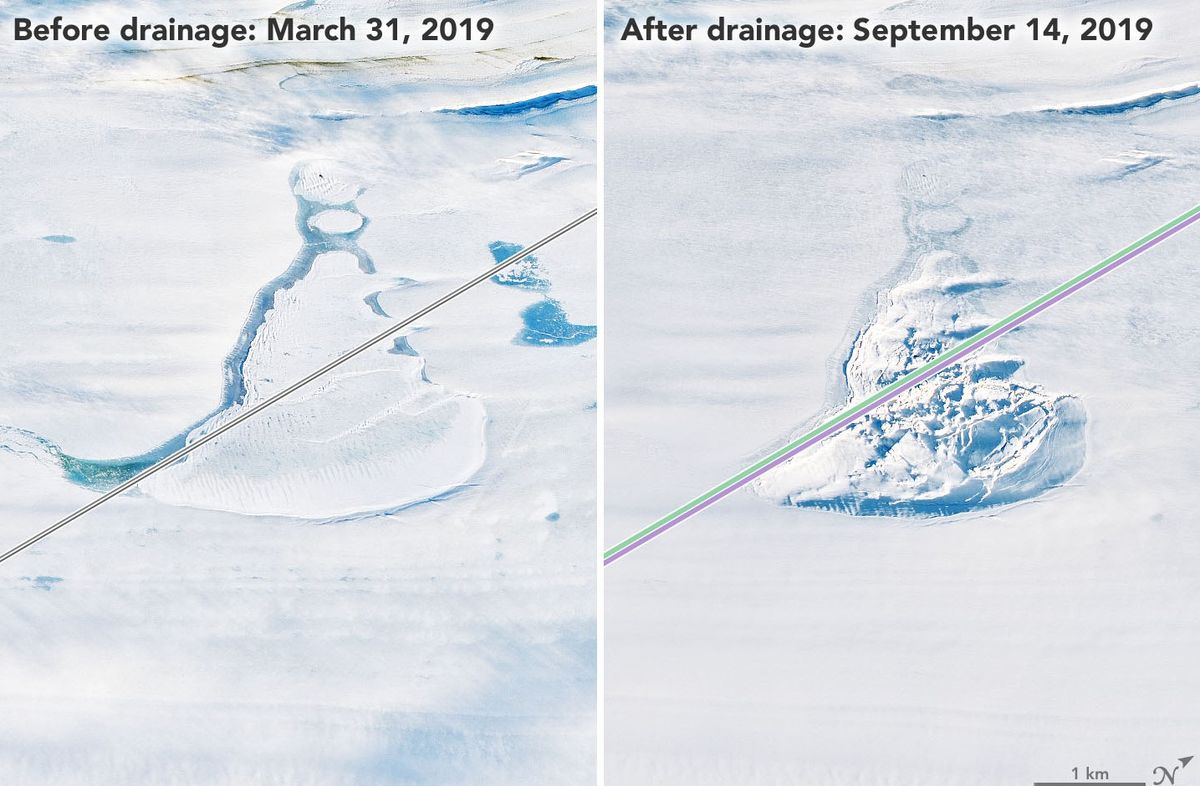

This aquatic system was largely invisible until the advent of NASA’s ICESat mission in 2003. The ICESat satellite used lasers to accurately measure the rise in Antarctic ice. In 2007, glaciologist Helen Amanda Fricker of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography connected elevation changes measured by ICESat to the dynamics of lakes deep below the ice surface. As the lakes empty and fill, the ice above rises and falls, offering clues as to what is going on below.

Fricker’s breakthrough opened up the possibility of tracking the lake system over time. However, ICESat only collected data for six years. Its equivalent from the European Space Agency, CryoSat-2, collected similar data from 2010 but over a larger area and with less precision. In September 2018, NASA launched a new satellite, ICESat-2, which collects the most accurate data to date.

“ICESat-2 is like putting on your glasses after using ICESat: the data is so precise that we can really start to draw the lake’s boundaries on the surface,” said Siegfried.

A dynamic system

In the new study, Siegfried and Fricker combined data from ICESat, CryoSat-2 and ICESat-2 to track changes in the subglacial lake system from October 2003 to July 2020. They focused on three areas with good satellite coverage and known active lakes: border between the Mercer and Whillans ice streams in West Antarctica; the lower MacAyeal ice, also in West Antarctica; and the Upper Glacier Academy in East Antarctica.

At the edge of Mercer and Whillans, the researchers discovered two new lakes, which they dubbed the Lower Conway Subglacial Lake and the Lower Mercer Subglacial Lake. They also discovered that what was thought to be a lake under the MacAyeal Ice Stream was actually two.

Over time, these lakes have undergone major changes. The lakes below the Mercer and Whillans Ice Stream boundary are currently undergoing their third drainage period in 17 years. During this time, all of the lakes under the MacAyeal Ice Creek followed their own drainage and infill patterns. The lowest lake experienced four fill-drain events during the study period, each taking only about a year. The second lake drained between 2014 and 2015 and is currently filling again, while the third lake drained slightly between 2016 and 2017. Meanwhile, the lakes below the Academy Glacier drained between 2009 and 2018.

All of these changes are pieces of the puzzle in scientists’ understanding of the speed and direction of the flow of the Antarctic ice sheet. Already, researchers are discovering links between lakes under ice and the ocean: In January, a study co-authored by Fricker found that the drainage of a lake on the Amery Ice Shelf in the East Antarctica dragged up to 198 billion gallons (750 billion liters) into the ocean in just three days, Live Science Reported at the time.

The new study was published on July 7 in the journal Geophysical research letters.

Originally posted on Live Science

[ad_2]

Source link