[ad_1]

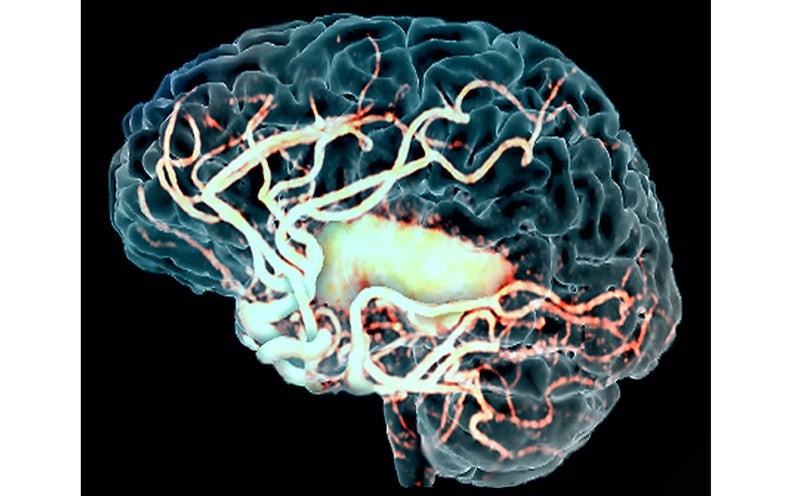

An experiment widely criticized last year saw a researcher in China remove a gene in embryonic twins to protect them from HIV. A new study suggests that using a drug to suppress the same gene in people with stroke or traumatic brain injury could help improve their recovery.

The new work shows the benefits of disabling the gene in stroke-induced mice using the drug, already approved as an anti-HIV treatment. It also focuses on a sample of people born naturally without the gene. The researchers found that people without genes recovered more quickly and completely from stroke than the general population.

The combined results suggest that the drug could stimulate recovery in humans following a stroke or traumatic brain injury, says S. Thomas Carmichael, principal investigator of the study and neurologist at the David Geffen School of Medicine at the University of Toronto. California to Los Angeles. His team started a follow-up study in humans to test the effectiveness of the drug.

The combination of mouse research and the exploitation of people's genetic data to confirm the relevance of drug targets makes this new research a "historical document," says Jin-Moo Lee, co-director of Barnes-Jewish Hospital. Hospital and cerebrovascular center of the University of Washington. in Saint Louis who was not involved in the work.

At the end of 2018, He Jiankui, then at the Southern University of Science and Technology in China, said he published the CCR5 the genes of the twins at the embryonic stage to protect them against HIV infection. The one-of-a-kind result was apparently healthy twin daughters born without CCR5, He said.

Carmichael and others have spent years researching genes and other biological pathways that could lead to the development of drugs to help the brain repair itself after a stroke or brain injury. CCR5 is the first candidate of this type to show real promise, say some experts. For patients with stroke or head trauma, "I believe this is the beginning of hope," says Alcino Silva, a neuroscientist at the University of California , United States. who worked with Carmichael on the new study. The results were published this week in Cell.

The drug used to block the activity of CCR5 has been on the market since 2007 and is approved as a treatment to slow the spread of HIV and AIDS. Carmichael administered the drug, called maraviroc, to stroke-induced mice. Abolishing gene activity in brain motor neurons "has had a dramatic effect on recovery," he says. The drug does not easily cross the blood-brain barrier, but enough to preserve the brain connections involved in chemical signaling and increase connectivity between brain regions, the study showed.

For the human validation component of the study, the team examined 68 people without CCR5 genes, with 446 controls. Those who suffered a stroke – and who also had the natural suppression of the gene – recovered their movement abilities faster and had fewer cognitive deficits several months after the stroke, than patients whose CCR5. The exact mechanism behind the result is unknown. In healthy people, the CCR5 The gene is thought to promote learning and memory by acting as a "stop" signal, inviting neurons to keep only one memory and keep it, rather than continuing to receive and retain each incoming signal, says Carmichael. Immediately after a stroke or brain injury, the gene helps reduce the excitability of neurons, thereby limiting damage, he says. But if the gene continues to emit stop signals, it also interferes with the brain's ability to make new connections and repair the damage, he adds.

Carmichael's approach is to deactivate these signals by encouraging patients to take the drug about five to seven days after a stroke and keeping them for about three months, allowing the brain to recover better. In ongoing clinical trials, participants also undergo intensive physical therapy to restore movement. This two-pronged therapeutic approach is important, says Steven Cramer, recovery expert after a stroke at the University of California at Irvine, who did not participate in the research. Pharmacotherapy can open the door to reconfiguring brain circuits, but recovery also requires individual effort, as does learning the task in the first place, he notes. "It's not because you're spreading magic goblin dust on the brain that you're solving the problem," he says. "You have to pair it with experiential training."

Cramer says that he thinks the treatment with anti-CCR5 the drugs could become "one of the main pillars" of therapeutic advances in recovery after stroke.

[ad_2]

Source link