[ad_1]

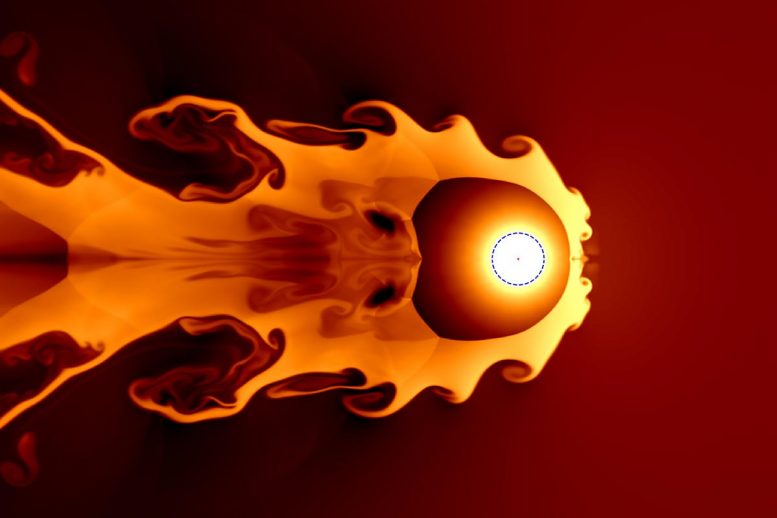

A team of researchers led by Professor Brian Fields speculates that a supernova about 65 light years away may have contributed to ozone depletion and subsequent late Devonian mass extinction , 359 million years ago. Pictured is a simulation of a nearby supernova hitting and compressing the solar wind. The orbit of the Earth, the blue dotted circle, and the Sun, the red dot, are shown to scale. Credit: Graphic courtesy Jesse Miller

Imagine reading by the light of an exploding star, brighter than a full moon – it may be fun to think about, but this scene is the prelude to disaster when the radiation devastates life as we know it. Killer cosmic rays from nearby supernovae could be the source of at least one mass extinction event, the researchers said, and the discovery of certain radioactive isotopes in Earth’s rock records could confirm this scenario.

New study from University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign professor of astronomy and physics Brian Fields explores the possibility that astronomical events were responsible for an extinction event that occurred 359 million ago years, at the border between the Devonian and Carboniferous periods.

The article is published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The team focused on the Devonian-Carboniferous boundary because these rocks contain hundreds of thousands of generations of plant spores that appear to be sunburned by ultraviolet light – evidence of a layer depletion event long-lasting ozone.

“Earth-based disasters such as large-scale volcanism and global warming can destroy the ozone layer as well, but the evidence for these is inconclusive for the time interval in question,” Fields said. “Instead, we propose that one or more supernova explosions, about 65 light years from Earth, could have been responsible for the prolonged loss of ozone.”

“To put this in perspective, one of the closest supernova threats today comes from the star Betelgeuse, which is over 600 light years away and well outside the destruction distance of 25 light years. Said a graduate student and co-author of the study. Adrienne Ertel.

The team explored other astrophysical causes of ozone layer depletion, such as meteorite impacts, solar flares, and gamma-ray bursts. “But these events end quickly and are unlikely to cause the lasting depletion of the ozone layer that occurred at the end of the Devonian period,” said Jesse Miller, graduate student and co- author of the study.

A supernova, on the other hand, delivers a double punch, the researchers said. The explosion immediately bathes the Earth with damaging UV, X-rays and gamma rays. Later, the explosion of supernova debris slams into the solar system, subjecting the planet to long-lasting irradiation from cosmic rays accelerated by the supernova. Damage to the Earth and its ozone layer can last up to 100,000 years.

However, fossil evidence points to a 300,000 year decline in biodiversity leading to the Devonian-Carboniferous mass extinction, suggesting the possibility of multiple catastrophes, possibly even multiple supernova explosions. “It’s entirely possible,” Miller said. “Massive stars generally occur in clusters with other massive stars, and other supernovae are likely to occur soon after the first explosion.”

The team said the key to proving that a supernova occurred would be finding the radioactive isotopes plutonium-244 and samarium-146 in the rocks and fossils deposited at the time of the extinction. “None of these isotopes occur naturally on Earth today, and the only way to get there is through cosmic explosions,” said Zhenghai Liu, undergraduate student and co-author.

The radioactive species born into the supernova are like green bananas, Fields said. “When you see green bananas in Illinois, you know they’re fresh and you know they haven’t grown here. Like bananas, Pu-244 and Sm-146 disintegrate over time. So if we find these radioisotopes on Earth today, we know they’re fresh and not from here – the green bananas of the isotopic world – and therefore the smoldering weapons of a nearby supernova.

Researchers have not yet looked for Pu-244 or Sm-146 in rocks of the Devonian-Carboniferous boundary. Fields’ team said their study aimed to define patterns of evidence in the geological records that would point to supernova explosions.

“The overarching message of our study is that life on Earth does not exist in isolation,” said Fields. “We are citizens of a larger cosmos, and the cosmos intervenes in our lives – often imperceptibly, but sometimes fiercely.

Reference: “Supernova triggers for end-Devonian extinctions” by Brian D. Fields, Adrian L. Melott, John Ellis, Adrienne F. Ertel, Brian J. Fry, Bruce S. Lieberman, Zhenghai Liu, Jesse A. Miller and Brian C . Thomas, August 18, 2020, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

DOI: 10.1073 / pnas.2013774117

Scientists from the University of Kansas also participated in the study; Kings College, United Kingdom; the European Organization for Nuclear Research, Switzerland; National Institute of Chemical Physics and Biophysics, Estonia; the United States Air Force Academy; and the University of Washburn.

The Council for Scientific and Technological Installations and the Estonian Research Council supported this study. Fields is also affiliated with the Illinois Center for Advanced Studies of the Universe.

[ad_2]

Source link