[ad_1]

For decades, Oregon’s healthcare system has been envied across the country.

Managed care organizations have enrolled a large portion of the population. Oregon’s health plan, designed in the 1990s, made care more accessible to the working poor.

The system was running smoothly. Reformers emphasized primary and preventive care, allowing the state to operate with the fewest hospital beds per capita in the country.

Then came the last wave of coronavirus. With the Delta variant sweeping the state, the scarcity of beds is suddenly a handicap.

Hospitals in rural areas with low vaccination rates have run out of space, leaving COVID-19 patients waiting for beds in emergency room corridors, waiting to be admitted to intensive care units at maximum .

Patients from the southwestern corner of Oregon, which suffered the brunt of the outbreak, have been transported to larger cities. But even urban hospitals were struggling to deal with the state’s fifth wave of COVID-19.

An unidentified patient is monitored on August 19 at Asante Three Rivers Medical Center in Grants Pass, Oregon. The increasing hospitalization rate of COVID-19 patients is reducing hospital capacity.

(Mike Zacchino / Associated press)

“We have deceased patients in emergency departments waiting for beds,” said Becky Hultberg, president and CEO of the Oregon Assn. hospitals and health systems. “In parts of Oregon we are looking at a collapsed system. “

Governor Kate Brown has deployed 1,500 National Guard members to more than 20 hospitals to clean, deliver supplies and defuse arguments between healthcare workers and patients and their families. Hospital officials are looking for palliative solutions, transforming offices into clinical space and calling on the public to be vaccinated.

The crisis is all the more frustrating given that on paper Oregon appears to be in fairly good shape compared to other states.

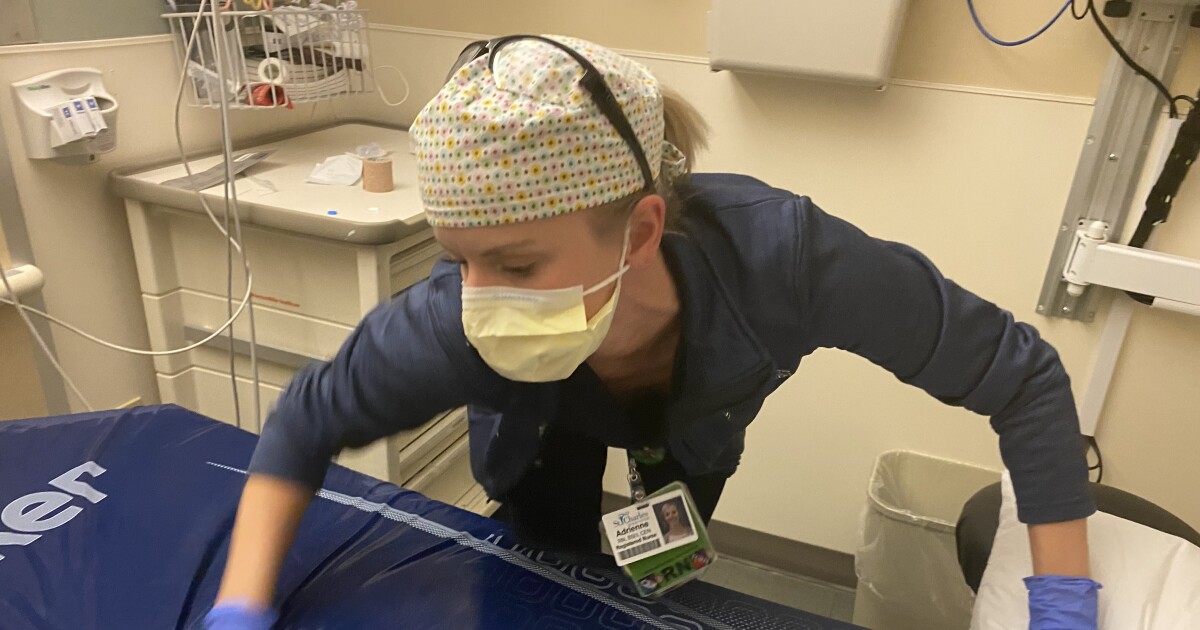

Administrator Kara Rowe dons protective gear and fills during a staff shortage as COVID-19 cases overwhelm St. Charles Medical Center in Bend, Oregon. As director of patient access for four hospitals, she manages a team of three dozen employees who have sometimes been short of 17 workers.

(Richard Read / Los Angeles Times)

Over the past week, it has averaged 49 new cases per day per 100,000 people, just above the national rate and less than half the rates in Mississippi, Louisiana and Florida – the states with the most hardest hit.

Oregon’s hospitalization rate is 22nd in the country and its death rate is 20th.

But the severity of the outbreak is magnified by the fact that Oregon has just 1.6 hospital beds per 1,000 people – up from a national average of 2.8 – and a shortage of healthcare workers to staff them. .

As of Friday, 363 of the state’s 4,222 general hospital beds were available. Of the 670 intensive care beds, 39 were available.

A record 866 COVID-19 patients have been hospitalized, including 241 in intensive care.

In the hard-hit rural southwest corner of the state, the three hospitals that make up Asante’s health system were over 90% full – and that was after increasing the total number of beds from 550 to 650. by converting single rooms into double rooms. and park stretchers in the hallways.

Each nurse looked after seven or eight patients, compared to the usual four.

Asante had more than 160 COVID-19 patients – a total that has grown rapidly and is expected to exceed 200 this week.

All elective surgeries were canceled.

“If you are not at risk of losing your life or a limb within 24 hours, you will not have surgery at our facility,” said Dr. James Grebosky, chief medical officer of the system. “We are keeping 64 patients who are ready to discharge, but we cannot find reception facilities for them.”

He said the region is home to 10% of Oregon’s population but accounts for more than a quarter of the state’s COVID patients.

Much of this is due to below-average vaccination rates – 46% in Jackson County and 40% in Josephine County, compared to 57% in the state and 51% nationally.

As the wave is concentrated in politically conservative counties, its effects are felt more widely as hospitals in other parts of the state struggle to deal with the overflow of patients.

Many ended up in Bend, the largest city in central Oregon, at St. Charles Medical Center, which last week converted an adjacent building into an emergency care clinic. As of Friday, the hospital only had 14 of its 225 beds available.

The St. Charles health system, which includes three other hospitals in outlying towns, has canceled or postponed nearly 3,000 surgeries for conditions such as cancer, heart disease and neurological disorders.

The system is also grappling with a labor shortage affecting the health sector across the state. Nurses were scarce nationwide even before the coronavirus hit, and burnout during the pandemic has led many to quit smoking.

With 3,400 full-time employees, St. Charles has 800 open positions, including nearly 200 vacant nursing positions. At a recent career fair, only 16 people showed up.

Like many hospitals in Oregon, St. Charles has a backlog of inpatients – Friday 29 – who are healthy enough to be discharged. But he’s struggling to find space in skilled nursing facilities, which are also full or unwilling to take in COVID-19 patients.

Larry Levitt, executive vice president of the Kaiser Family Foundation, said Oregon and other states caught in power surges were still “in the process of coming to terms with each other and were not fully prepared for this. crisis”. To create surge capacity, “you need almost the public health equivalent of military reserves.”

The most prominent architect of healthcare reform in Oregon was John Kitzhaber, a former emergency physician who served as governor for 12 years between 1995 and 2015. The approach, which minimized costly hospital admissions, was hailed for providing maximum health benefits to a wider audience. population, although critics see it as rationing.

In an interview on Friday, Kitzhaber noted that the state had saved money, committing to the federal government to reduce the growth of Medicaid spending while creating a system of community care organizations operating on a fixed budget, helping beneficiaries manage chronic illnesses such as diabetes.

But he also acknowledged that reformers had not designed the system to handle a pandemic-wide crisis.

“You can’t plan your system around an event like this,” he said. “What we haven’t done is plan the event itself.”

Either way, higher vaccination rates would have reduced the pressure on hospitals, he said.

Health workers in southern and central Oregon are dismayed that the vaccination campaign appears to have stalled and members of the public appear oblivious or indifferent to the hospital crisis.

“Who knows, I might die of COVID next week, but I sincerely doubt it,” said Cassandra Torgrimson, a 49-year-old school receptionist in Bend.

She said she quit a former job in the retail industry to avoid having to wear a mask and that she did not see the need to be vaccinated, believing that the herbs, essential oils and the fresh air would keep her healthy.

Another resident, Mary Moore, said she had been vaccinated but also avoided masks and viewed complaints from health workers as exaggerated.

“They’re complaining,” said Moore, 59, a retired hospital administrative worker. “This is the job they signed up for.

Cassandra Torgrimson – caring for goats in central Oregon, where COVID-19 cases plague hospitals – has decided not to get the vaccine. The 49-year-old has heard that people can die from vaccines as much as they can die from COVID-19, and aims to stay healthy with herbs, essential oils and fresh air.

(Richard Read / Los Angeles Times)

It wasn’t that long ago that Oregon, like much of the country, appeared to be emerging from the pandemic. At the end of June, Brown lifted social distancing rules, bar and restaurant capacity limits and the requirement for masks in public spaces.

“Better days are ahead,” said the governor at the time. “It actually means Oregon is 100% open for business. “

But since then, the average number of new infections each day has risen from less than 200 to over 2,000.

This month, Brown reinstated the mask’s mandate, regardless of vaccination status.

On Thursday, she announced that health workers would no longer be allowed to opt out of vaccinations by regularly undergoing testing for COVID-19. “We need every frontline healthcare worker to be healthy and available to treat patients,” she said.

[ad_2]

Source link