[ad_1]

If last year’s climate change fueled mega-fires, and we’ve learned anything from the global pandemic, it’s how interconnected we are with each other and with our environment. Now we have some preliminary clues that climate change and the cause of the pandemic may also be linked – through bats.

Bats have a notorious ability to live with viruses that destroy other animals. While their overpowered immune system has been a blessing to them – allowing these aerial mammals to thrive around the world – it is a curse for the rest of us, as they carry these viruses with them wherever they go.

Now, a new study has found that with the warming of the climate over the past century, increasing sunlight, carbon dioxide, and changes in precipitation have converted southern China’s tropical shrubs into savannahs and woods – prime habitat for bats. And more than 40 new species of bats have moved in.

“Understanding how the global distribution of bat species has evolved due to climate change may be an important step in reconstructing the origin of the COVID-19 epidemic,” said zoologist Robert Beyer of the University of Cambridge.

To study this, Beyer and his colleagues used data on global vegetation, temperature, precipitation, cloud cover, and the vegetation requirements of the world’s bat species to construct a map of their distribution in the early years. 1900. They then compared this to the current distributions of cash.

“As climate change altered habitats, species left some areas and moved to others – taking their viruses with them,” Beyer explained. “This not only changed the regions where viruses are present, but most likely allowed new interactions between animals and viruses, causing the transmission or evolution of more dangerous viruses.”

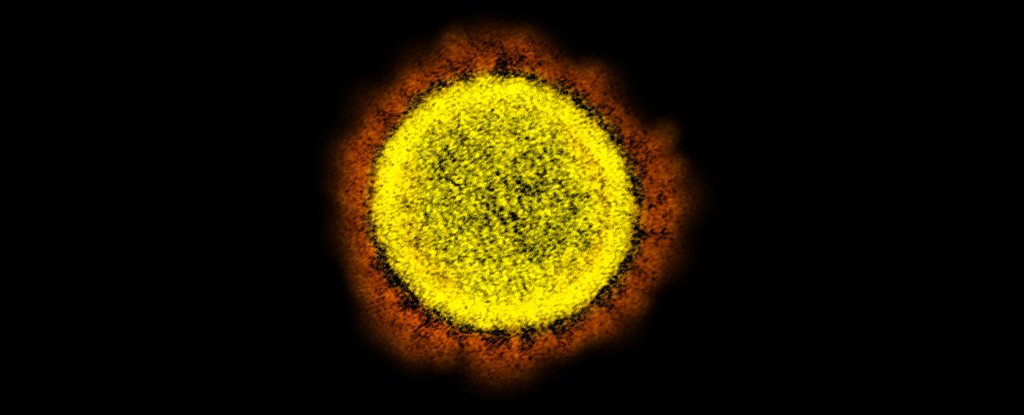

Change in the global distribution of bats since 1901. (Beyer et al, 2021)

Change in the global distribution of bats since 1901. (Beyer et al, 2021)

Three out of four emerging infectious diseases in humans are zoonoses – they come from animals. And coronaviruses make up more than a third of all sequenced bat viruses. The building blocks of the 2002 SARS pandemic were found in bats from a single cave, and now their bodies are the main suspects of brewing the precursors to SARS-CoV-2.

Between them, the 40 relatively recent migrating bat species in China’s Yunnan province carry more than 100 types of coronavirus. Genetic evidence suggests that the ancestor of SARS-CoV-2 comes from this same region.

Most of these coronaviruses cannot infect us, however. And now, some species of bats are being falsely prosecuted for other species that unintentionally wreak havoc on us, even though these animals play a crucial role in our ecosystems. At least 500 plant species depend on bat pollination (such as bananas, mangoes, and agaves), other plants depend on their droppings, and some species control insects (including annoying and disease-spreading mosquitoes) by devouring them.

But our relentless walk further and further into remaining natural habitats, through processes, like deforestation, which also lead to climate change, increases our interactions between these animals and therefore our chances of encountering their viruses. Degraded habitats also stress and weaken the immune systems of animals within them, making it more likely for viruses to mutate into something that can cross species barriers.

“Among endangered wildlife species, those whose populations have declined due to exploitation and habitat loss shared more viruses with humans,” a study found last year.

Beyer and his team warn that we do not yet know the exact origin of SARS-CoV-2, so their inferences are not yet conclusive and further studies based on different vegetation and using different models are needed to corroborate their findings. results. Other variables that may have an impact on the distribution of bats, such as invasive species and pollution, also need to be investigated.

And while the correlation does not equal causation, a growing body of research suggests that climate change is a driver of pathogens infecting new hosts. We even have examples where historic global climate change has been associated with environmental disturbances that have led to the emergence of infectious diseases.

“The fact that climate change can accelerate the transmission of pathogens from wildlife to humans should be an urgent wake-up call to reduce global emissions,” said biogeographer Camilo Mora of the University of Hawaii, Manoa .

To reduce these risks, Beyer and colleagues strongly recommend introducing measures to limit human-wildlife interactions, including imposing strict regulations on hunting and wildlife trade, discouraging dietary customs. and medicinal products that depend on wildlife and setting strict animal welfare standards on farms, markets and transportation. Vehicles. To do this, we must consider the socio-economic needs that motivate these practices that they note in their article.

Protecting natural habitats is also essential to keep species healthy, a measure that can also help mitigate climate change.

Given the possibility raised by our analysis that global greenhouse gas emissions may have contributed to the SARS-CoV-1 and SARS-CoV-2 outbreaks, we echo the calls for decisive mitigation climate change, including in the context of COVID-19 economic recovery programs, ”insists the team.

This research was published in the Total environmental science.

[ad_2]

Source link