[ad_1]

SALT LAKE CITY – The number of patients at Primary Children’s Hospital diagnosed with a coronavirus-related complication has doubled from the past two months.

In fact, there are now more than 1,500 confirmed cases of multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children, otherwise known as MIS-C. The syndrome develops after the child has been infected with SARS-CoV-2.

As medical experts try to unravel the long-term effects of COVID-19, officials at the Children’s Primary Hospital announced on Tuesday that they would begin the first trimester study of MIS-C.

Long-term results after multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children, called the MUSIC study, will seek to explain how MIS-C affects children who were diagnosed five years after their development.

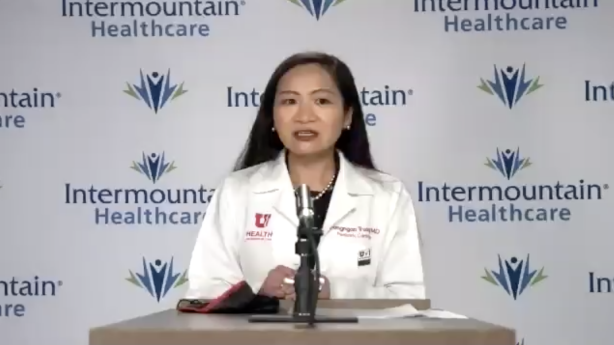

This massive project will include work from more than 30 children’s hospitals in the United States and Canada. It’s funded by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, said Dr Ngan Truong, a pediatric cardiologist at the University of Utah Health and Intermountain Primary Children’s Hospital, and co-lead of the study.

“The MUSIC study comes at an important time,” she says. “My colleagues and I at Intermountain Primary Children’s Hospital have treated dozens of young patients with MIS-C at this stage, and we continue to care for them after their hospitalization.

The first impacts of MIS-C

In October, 12-year-old Madilyn Dayton, of Cokeville, Wyoming, woke up to be in immense pain. She couldn’t move much and ended up in the Children’s Primary Hospital, where she was quickly diagnosed with MIS-C.

Her family had no idea she had even been exposed to COVID-19 because no one in the household of eight had exhibited symptoms or tested positive. What started out as flu-like symptoms quickly turned into something much more serious.

Madilyn and her mother, Marilyn Dayton, shared their story late last year. A few months later, Madilyn said she “is doing a lot better now”.

“I still get tired a lot easily, but other than that everything is almost back to normal,” she said, joining the announcement of the video chat study with her mother.

Marilyn Dayton said she had prevented Madilyn from attending classes in person since her diagnosis as a precaution and due to her chronic fatigue. Once an active child who participated in many sports, Madilyn was out of breath after five minutes of shooting basketball.

“We noticed the fatigue part,” said Marilyn Dayton. “I don’t know if she could get up and do a full day of school and handle it all right now. She still sleeps a lot.

There are still a lot of unknowns about MIS-C, which is why Madilyn will be participating in the new long-term study. The post-coronavirus complication causes all kinds of different reactions, and it’s unclear how long they last.

Truong explained that MIS-C is a rare complication of COVID-19 infection thought to be the result of an “extreme immune response” to SARS-CoV-2. It mainly affects school-aged children, but has also been reported in infants and young adults. Symptoms include fever, abdominal pain, diarrhea, red eyes, rash, and fatigue.

This can lead to serious disease of several organ systems, such as the heart, lungs, blood, kidneys or brain. Children who develop MIS-C are often hospitalized and require intensive care due to low blood pressure, shock, or heart problems.

The total number of children hospitalized at the Primary Children’s Hospital with MiS-C since the start of the pandemic is around 50, but the number is increasing, Truong said. The hospital has reported around 30 new cases since mid-November. The increase in MiS-C cases appears to follow similar patterns regarding an increase in coronavirus-related child hospitalizations in Utah, which was highlighted in a University of Minnesota study.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has reported 1,626 cases of MIS-C nationwide since April 2020. They also reported 26 deaths of children who had exhibited symptoms that matched its definition of the syndrome.

Since the COVID-19 vaccine has yet to be approved for children, experts say the only thing to slow MIS-C is protective measures to combat the spread of the coronavirus.

The data also shows that a disproportionate number of blacks and Latinos have been affected, Truong added. Still, there aren’t many answers to understand the syndrome, such as why some children end up with it.

“MIS-C is largely a mystery at this point,” she said. “We don’t yet know what risk factors cause some children with COVID-19 to develop MIS-C and others not.”

These unknowns also include whether it could lead to serious long-term effects like scarring to the heart, which can lead to serious heart problems and possibly even death. The unknowns about the heart are one reason some pediatricians may advise a three to six month recovery period before physical activity such as playing sports.

In search of answers to long-term effects

The possible long-term effects go beyond the heart. The study could determine how long Madilyn’s documented chronic fatigue will last. It – along with difficulty concentrating – has been shown to be a longer side effect of COVID-19 in adults, Truong said.

Researchers will also delve into examining long-term effects on the nervous system, lungs, immune system, and gastrointestinal systems. This will be done by reviewing hospitalization and follow-up appointment data as well as annual telephone interviews with participants to check their symptoms after the time has elapsed.

Many hospitals were already doing follow-ups for up to six months to check with MIS-C patients, so the study will look at the results that were collected from participating hospitals.

“We will also be looking for genetic clues about disease risk and outcome,” Truong said. “We will use this information to create evidence-based treatment guidelines for MIS-C that will help pediatricians better identify and respond to children with symptoms of MIS-C.

I wanted answers … Unless they do studies like this and find participants to participate in, they can’t get those answers.

– Marilyn Dayton

For Truong, she finds the study relevant to families of children diagnosed with MIS-C. She said she often gets questions from parents who want to know if their children’s symptoms at that time will persist in the future – and for how long.

These are questions to which she had no answers.

“Unfortunately, I don’t have a clear answer for them at the moment, and the data we have is currently very limited. However, I hope that in the years to come we will have more answers for parents and for my patients., “she said. “We hope the data from the MUSIC study will help us provide us with long-term advice and follow-up strategies for children and young adults, for example if we need to restrict them.”

Marilyn Dayton is one of the parents who wondered about the future of her child. While she and Madilyn wish they had the answers now, they jumped at the chance to participate in the study.

This is something they said they never really questioned or doubted.

“I wanted answers,” said Marilyn Dayton. “Unless you do studies like this and find participants to participate in it, they can’t get those answers.”

Related stories

Other stories that might interest you

[ad_2]

Source link