[ad_1]

It seems that every week another rocket is launched into space carrying rovers to Mars, tourists or, more often, satellites. The idea that “space gets cluttered” has been around for a few years now, but how cluttered is it? And how many people are there going to be?

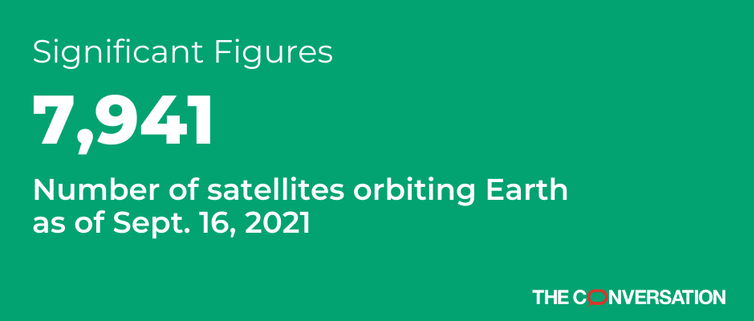

I am a professor of physics and director of the Center for Space Science and Technology at the University of Massachusetts, Lowell. Many satellites in orbit have died and burned in the atmosphere, but thousands remain. Groups that track satellite launches don’t always report the exact same numbers, but the overall trend is clear – and startling.

Since the Soviet Union launched Sputnik – the first man-made satellite – in 1957, humanity has steadily put more and more objects into orbit every year. During the second half of the 20th century, there was slow but steady growth, with around 60 to 100 satellites launched each year until the early 2010s.

But since then, the pace has accelerated considerably.

By 2020, 114 launches have transported approximately 1,300 satellites into space, for the first time surpassing the threshold of 1,000 new satellites per year. But no year in the past compares to 2021. As of September 16, about 1,400 new satellites have already started circling the Earth, and this will only increase as the year progresses. Just this week, SpaceX deployed 51 more Starlink satellites into orbit.

Small satellites, easy access to orbit

There are two main reasons for this exponential growth. First, it has never been easier to send a satellite into space. For example, on August 29, 2021, a SpaceX rocket transported several satellites – including one built by my students – to the International Space Station. On October 11, 2021, these satellites will deploy into orbit and the number of satellites will increase again.

The second reason is that rockets can carry more satellites more easily – and at lower cost – than ever before. This increase is not due to the fact that rockets are getting more powerful. On the contrary, satellites have become smaller thanks to the electronic revolution. The vast majority – 94% – of all spacecraft launched in 2020 were small satellites – satellites weighing less than about 1,320 pounds (600 kilograms).

The majority of these satellites are used for Earth observation or for communications and the Internet. In an effort to bring the internet to underserved areas of the world, two private companies, Starlink by SpaceX and OneWeb, have jointly launched nearly 1,000 small satellites in 2020 alone. They each plan to launch more than 40,000 satellites. in the coming years to create what are called “mega-constellations” in low Earth orbit.

Several other companies are eyeing this $ 1 trillion market, including Amazon with its Kuiper project.

A crowded sky

With the enormous growth of satellites, fears of a crowded sky are starting to come true. A day after SpaceX launched its first 60 Starlink satellites, astronomers began to see them block the stars. While the impact on visible astronomy is easy to understand, radio astronomers fear losing 70% of sensitivity in some frequencies due to interference from mega-satellite satellites like Starlink.

Experts studied and discussed the potential problems posed by these constellations and the means by which satellite companies could solve them. These include reducing the number and brightness of satellites, sharing their location, and supporting better image processing software.

As low Earth orbit becomes congested, concerns about space debris increase, as does the real possibility of collisions.

Future trends

Less than 10 years ago, the democratization of space was a goal to be achieved. Now, with student projects on the Space Station and over 105 countries with at least one satellite in space, it could be argued that this goal is within reach.

Every disruptive technological advance requires updating the rules – or creating new ones. SpaceX has tested ways to reduce the impact of the Starlink constellations, and Amazon has announced plans to deorbit its satellites within 355 days of the mission’s end. These and other actions by different stakeholders give me hope that trade, science and human efforts will find lasting solutions to this potential crisis.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

[ad_2]

Source link