[ad_1]

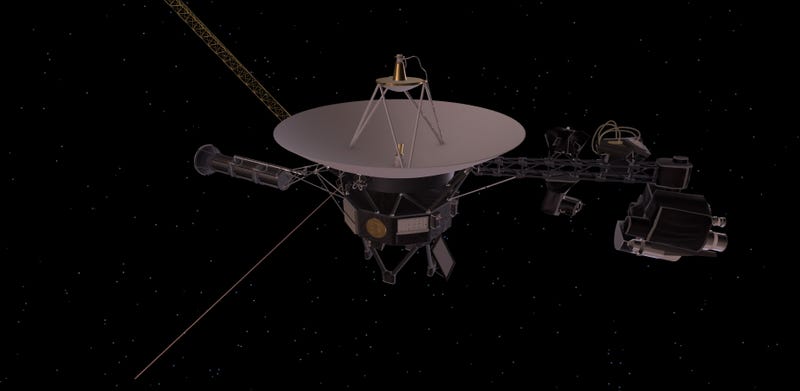

Launched 42 years ago, the Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 space probes are now exploring the outer realms of our solar system. Unfortunately, the end of the mission is now well in sight, but NASA has planned to keep the probes operational for as long as possible before their food is exhausted.

Voyager 1 and 2 were launched in 1977 at 16 days apart. The two probes visited Jupiter and Saturn, but Voyager 2 was sent on a trajectory that allowed him to overtake Uranus and Neptune. Since then, the probes have traveled farther and farther into the deep space, at speeds approaching 56,000 kilometers at the time. The probes are now more than 18 billion kilometers from the Earth. Voyager 1, the farthest of the two, is so far away that a radio signal from Earth traveling at the speed of light requires 20 minutes to reach the probe.

Unfortunately, and like all good things, this historic mission will end. The probes should continue to operate until the mid-2020s. After that, they will not have enough power to power their heaters. Eventually, the embedded components will freeze, turning the probes into two pieces of dead metal crossing the gap.

But while the end of the mission is inevitable, NASA will not let the probes enter gently into this good heavenly void. As the agency noted in a recent press release, Voyager's engineers plan to make changes to extend the lifespan of the probes to the maximum. NASA's new "Energy Management Plan" is designed to ensure that Voyager probes work so that scientific data can continue to be collected at the heliopause, the boundary between the solar wind (particles released by the solar corona) and interstellar space.

Needless to say, the situation is getting a bit chilly for travelers, who risk freezing so far from the sun. A frozen fuel line, for example, would make their propellers unusable, preventing the probes from orienting their antennas and communicating with the Earth. That's why they are equipped with a power supply and several heating units, as explained by NASA:

Each of the probes is powered by three radioisotope thermoelectric generators, or RTGs, which produce heat through the natural decay of the plutonium 238 radioisotopes and convert this heat into electrical energy. Since the thermal energy of plutonium in GTRs decreases and their internal efficiency decreases over time, each spacecraft produces about 4 watts less electricity each year. This means that the generators produce about 40% less than the launch nearly 42 years ago, limiting the number of systems that can operate on the spacecraft.

Decreasing power (radioisotope thermoelectric generators are not expected to last well beyond 2025), NASA must decide which components will get the juice needed for the heaters and which will not. As a result, the Agency's new energy management system considers "multiple options to cope with the decrease in the energy supply of both spacecraft, including the shutdown of additional space heaters for instruments in the next few years, "notes NASA.

The situation with Voyager 2 is more urgent because it has more instruments requiring energy. Voyager engineers have recently decided to stop heating that warms its Cosmic Ray (CRS) subsystem. This instrument records information about the probe's environment and the interactions of the heliosphere with the solar wind flowing in that region of space. It should be noted that the Voyager 2 remote restraint system is not dead – it records and restores data to Earth, even though it is now operating at temperatures below those in which it was tested.

"It's amazing that Voyagers' instruments have been so robust," said Suzanne Dodd, Voyager project participant in NASA's press release. "We are proud that they have stood the test of time. The long life of the spacecraft means we are confronted with scenarios we never imagined. We will continue to explore all options available to enable travelers to make the best science possible. "

Other instruments, including plasma measuring devices and magnetic fields, continue to receive heat from their radiators. At least for the moment.

The propellants of the probe, which are fed with hydrazine, is another important consideration. These thrusters are essential to operations in that these thrusters, thanks to their tiny impulses, rotate the spacecraft. Two years ago, NASA needed to reorient Voyager 1, but it took more impulses than usual, which required the triggering of a set of unused thrusters for 37 years. The episode showed that Voyager's thrusters were gradually weakening over time and that a similar adjustment had to be made on Voyager 2 – a change that should occur later this month.

But any adjustment will be helpful because NASA is trying to make the most of the latest traces of these historical probes, which provide unprecedented data for scientific analysis.

"The two Voyager probes explore areas never visited before, so every day is a day of discovery," said Voyager project researcher Stone. "Traveling will continue to surprise us with new ideas about deep space."

The contents of the first spatial postcard of humanity and how to read it

Voyager I now flies officially in interstellar space. In the future, an extraterrestrial spaceship could …

Read more

Once dead, the probes will continue to travel farther into deep space. At their current speed, they would have to cross the Oort cloud – the area in which the gravity of the Sun no longer dominates – in about 40,000 years, two light years from Earth. Relentlessly, the probes could eventually reach another stellar system, including a system inhabited by an intelligent extraterrestrial civilization. If that happened and one of the probes was intercepted, the aliens would find a golden disc indicating that they are not alone in the universe.

[ad_2]

Source link