[ad_1]

The largely featureless surface of the Greenland ice sheet, viewed from the window of a P3 aircraft carrying geophysical instruments aimed at detecting geological features below. Credit: Kirsty Tinto / Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory

Currently inaccessible, a single site may contain secrets from the past.

Scientists have detected what they say is sediment from a huge ancient lake bed sealed more than a mile under the ice of northwest Greenland – the very first discovery of such a subglacial feature in the world. Apparently formed during a time when the area was ice free but now completely frozen over, the lake bed may be hundreds of thousands or millions of years old and contain unique fossil and chemical traces from past climates and life. Scientists consider this data to be critical to understanding what the Greenland ice cap could do in the years to come as the climate warms, and the site therefore makes an attractive target for drilling. An article describing the discovery is in press in the newspaper Earth and planetary science letters.

“This could be an important repository of information, in a landscape that is currently totally hidden and inaccessible,” said Guy Paxman, postdoctoral researcher at Columbia universityLamont-Doherty Earth Observatory and main author of the report. “We are trying to understand how the Greenland ice sheet has behaved in the past. This is important if we are to understand how it will behave in the decades to come. The ice sheet, which is melting at an accelerated rate in recent years, contains enough water to raise global sea level by about 24 feet.

The researchers mapped the lake bed by analyzing data from airborne geophysical instruments capable of reading signals entering the ice and providing images of the geological structures below. Most of the data came from aircraft flying low over the ice cap as part of NASAOperation IceBridge.

A newly formed lake on the edge of the Greenland ice cap, exposing the sediment released by the ice. These lake beds become common as the ice recedes. Credit: Kevin Krajick / Earth Institute

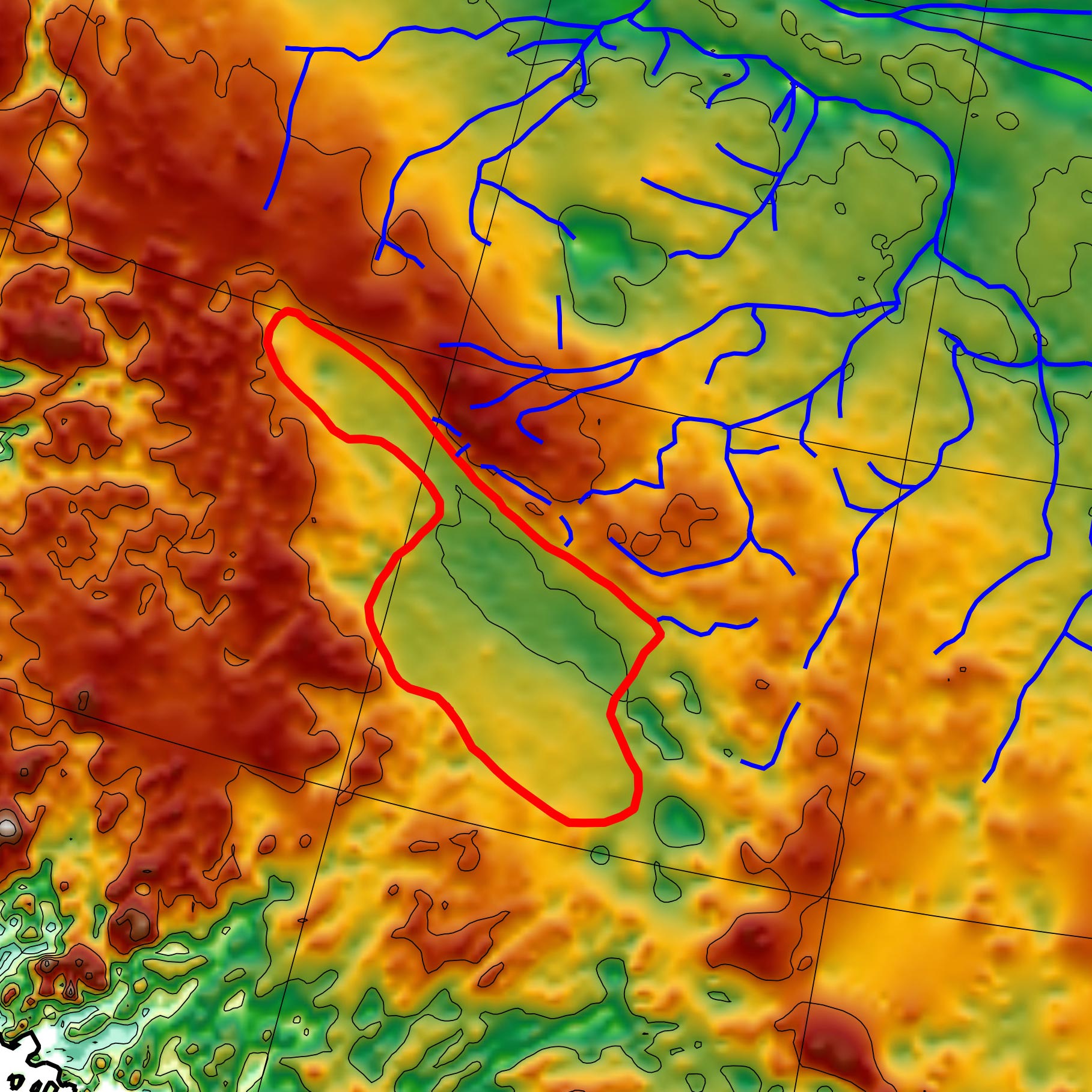

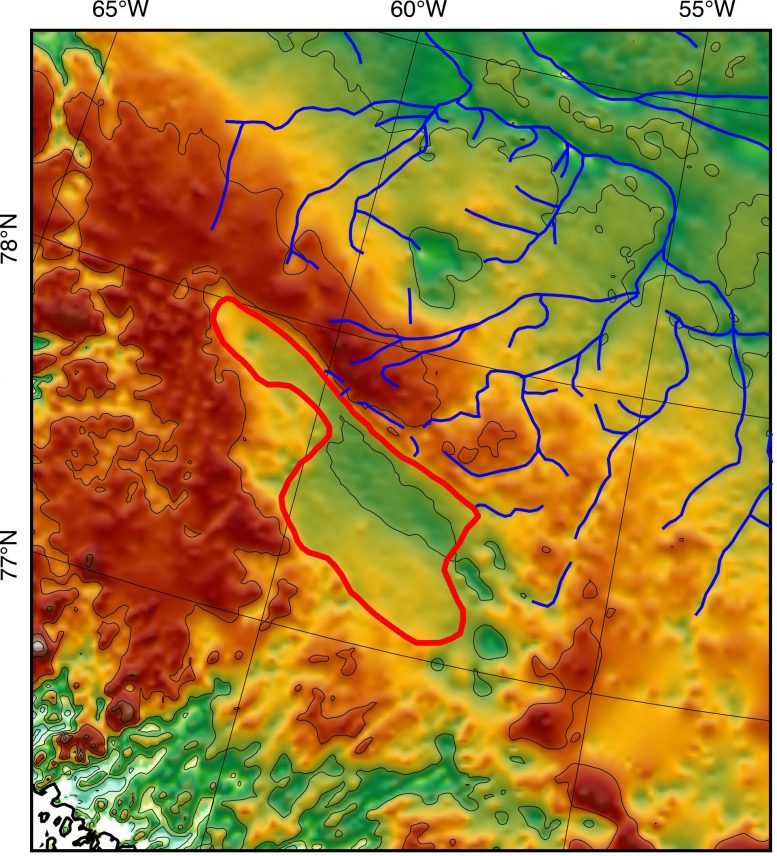

The team says the basin was once home to a lake covering about 7,100 square kilometers (2,700 square miles), roughly the size of the US states of Delaware and Rhode Island combined. The sediment in the basin, shaped loosely like a meat cleaver, appears to be up to 1.2 kilometers (three-quarters of a mile) thick. The geophysical images show a network of at least 18 apparent stream beds once carved into adjacent bedrock in a sloping escarpment to the north that must have fed into the lake. The image also shows at least one apparent outlet stream to the south. The researchers calculate that the depth of the water in the old lake ranged from about 50 meters to 250 meters (a maximum of about 800 feet).

In recent years, scientists have discovered existing subglacial lakes in Greenland and Antarctica, containing liquid water sandwiched in ice or between bedrock and ice. This is the first time anyone has spotted a fossil lake bed, apparently formed in the absence of ice, then covered and frozen in place. There is no evidence that the Greenland Basin contains liquid water today.

Paxman says there’s no way to tell the age of the lake bed. Researchers say it’s likely that ice has periodically advanced and retreated over much of Greenland over the past 10 million years, and possibly as far back as 30 million years. A 2016 study led by Lamont-Doherty geochemist Joerg Schaefer suggested that most of Greenland’s ice may have melted for one or more extended periods over the past million years or so, but the details are fragmentary. This particular area could have been covered and uncovered over and over again, Paxman said, leaving a wide range of possibilities for the history of the lake. Either way, Paxman says, the substantial depth of the sediment in the basin suggests that it must have accumulated during ice-free periods over hundreds of thousands or millions of years.

“If we could get to these sediments, they could tell us when the ice was present or not,” he said.

Using geophysical instruments, the scientists mapped a huge ancient lake basin (pictured here in red) under the Greenland ice, covering about 2,700 square miles). Redder colors mean higher altitudes, green lower. A stream system incised in the bedrock that once fed the lake is shown in blue. Credit: Adapted from Paxman et al., EPSL, 2020

Researchers put together a detailed picture of the lake basin and surrounding area by analyzing radar, gravity and magnetic data collected by NASA. The ice penetrating radar provided a basic topographic map of the land surface underlying the ice. This revealed the contours of the smooth, low basin, nestled among the higher elevation rocks. Gravity measurements have shown that the material in the basin is less dense than the surrounding hard metamorphic rocks – evidence that it is composed of sediment dragged in from the sides. Measurements of magnetism (sediments are less magnetic than solid rock) helped the team to map sediment depths.

Researchers say the basin may have formed along a now long dormant fault line, when bedrock expanded and formed a low point. Alternatively, but less likely, previous glaciations may have widened the depression, leaving it to fill with water as the ice receded.

What the sediment might contain is a mystery. The material washed away from the edges of the ice sheet contains remnants of pollen and other material, suggesting that Greenland may have experienced warm periods over the past million years, allowing plants and possibly even be in the forests to settle. But the evidence is inconclusive, in part because it is difficult to date such loose material. The newly discovered lake bed, on the other hand, could provide an intact archive of fossils and chemical signals dating from a so far unknown distant past.

The basin “could therefore be an important site for future under-ice drilling and the recovery of sediment records which could provide valuable information on the glacial, climatological and environmental history” of the region, the researchers write. With the top of the sediment lying 1.8 km below the current ice surface (1.1 miles), such drilling would be intimidating, but not impossible. In the 1990s, researchers penetrated nearly 2 miles into the summit of the Greenland ice sheet and recovered several feet of bedrock – at the time, the deepest ice core ever drilled. The feat, which lasted for five years, has not been repeated since in Greenland, but a new project to reach shallower bedrock in another part of northwest Greenland is planned for the next few years.

Reference: Earth and planetary science letters.

The study was co-authored by Jacqueline Austermann and Kirsty Tinto, both also based at Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory. The research was funded by the US National Science Foundation.

[ad_2]

Source link