[ad_1]

The classic sci-fi writer Jules Verne has already imagined an entire underground landscape at the heart of the planet, with prehistoric species and extinct plants. The book was well titled Journey to the Center of the Earth.

We may not have found dinosaurs here, but new research reveals features of the underground world resembling structures on the surface. Far from a bubbling mess, there are deep mountains that rival anything here.

Geophysicists from Princeton University in the United States and the Chinese Academy of Sciences have used the echoes of a gigantic earthquake that struck Bolivia two decades ago to replenish the deep topography.

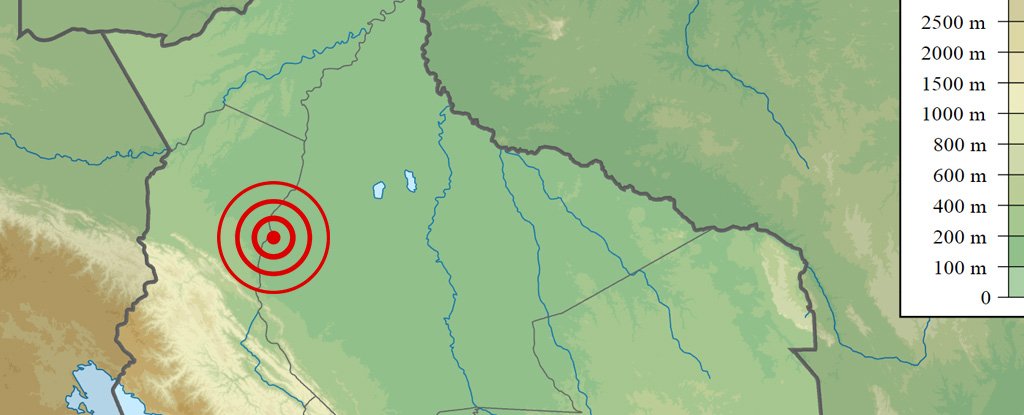

On June 9, 1994, a quake with a magnitude of 8.2 rocked a sparsely populated area of the Amazon in the South American nation. Nothing so powerful had been seen for decades, with shocks being felt as far away as Canada.

"Earthquakes of this magnitude do not occur very often," said geoscientist Jessica Irving.

Not only was it big, it was deep, with a focal point estimated at just under 650 kilometers deep. Unlike earthquakes that cross the crust, the energy of these monsters can shake the whole coat like a bowl of jelly.

This earthquake was one of the first to be measured on a modern seismic network, providing researchers with unprecedented recordings of waves breaking across the interior of our planet.

Just like the sound waves of an ultrasound can reveal differences in the density of tissues inside a body, the huge waves pulsating into the bowels of the Earth as its crust shudders and falls apart. rubs against itself can be used to create an image of what is there.

It is only recently that geoscientists have used signatures in these waves to determine the rigidity of the planet's core.

In this case, the researchers took advantage of the intensity of the 1994 earthquake to detect the dispersion of the waves during their transition between the layers, thus revealing the details of the boundaries.

"We know that almost all objects have a surface roughness and therefore a diffused light, which is why we can see these objects.The scattered waves carry information about the roughness of the surface", explains L & # 39; Lead author Wenbo Wu, a geoscientist at the California Institute of Technology.

"In this study, we studied scattered seismic waves propagating inside the Earth to limit the roughness of the Earth's 660 kilometers."

At this depth, there is a division between the more rigid lower parts of the mantle and an upper zone less subject to sufficient pressure, which creates a discontinuity marked by the appearance of various minerals.

The deepest hole we have ever dug has a minimum depth of 12 km. Therefore, without a tunnel up to Jules Verne to drop us off, we do not know what this transition area looks like. Until now.

Based on these important waves crossing the border, the researchers concluded that the meeting point between the upper and lower parts of the mantle is a zigzagged mountain range that shames everything on the surface.

"In other words, a border stronger than the 660 kilometers is present on the Rocky Mountains or Appalachians," Wu said.

This serrated line has important implications for the formation of the Earth. Most of our planet's mass is made up of coats. Knowing how it mixes and changes by transferring heat tells us about its evolution.

Different evidence has produced competing models of how minerals flow and disintegrate in pressurized rock, with some claiming that mixtures are well mixed, others suggesting interference at the boundary.

Knowing the details of this underground mountain could decide the fate of various models describing the history of the ever-changing geology of our planet.

"What's interesting with these results, is that they provide us with new information to understand the fate of ancient tectonic plates that have descended into the mantle and where the ancient mantle material could still reside, "says Irving.

It may not be an easy place to explore. And forget the giant behemoths and giant insects. But the world lost under our feet still hints at our past if we know where to look.

This research was published in Science.

[ad_2]

Source link