[ad_1]

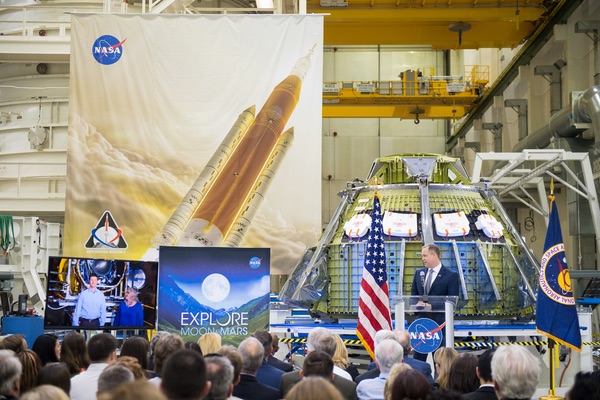

NASA insists on the value of exploration for its manned space flight program, but the most important elements, such as SLS and Orion, are the jobs created. (credit: NASA / Aubrey Gemignani) |

by Roger Handberg

Monday, March 25, 2019

![]()

Going on the Moon or on Mars is often explained as a wink to human desire to explore the unknown: the infinite perspective of borders, often cited in the reasons why humans roam the hill neighbor to see what there is. Since its inception, manned spaceflight – once devoid of Cold War motivations – has been a constant pursuit of extending the reach of human activity to the unknown. There are gestures of practicality in calls to planetary exploration so that we can see why Mars has turned into desert and Venus into hell of intense heat and pressure. Why these planets moved in different directions becomes an intellectual puzzle whose answers can serve as vehicles to survive a potentially catastrophic future here on Earth. This, in turn, often reinforces the need to pursue human spaceflight: the Moon or Mars as a refuge from a dying Earth. The struggle, then, is to make space science and other missions work because of their long-term social utility, without necessarily benefiting from the traditional sense of economic loss and profit.

This is not enough

Building a space program solely on the quest for the unknown has proven to be a difficult activity, an activity that often meets with opposition. This state of affairs is not necessarily the product of views completely hostile to the quest, but rather of a vision built on perspectives emphasizing different priorities. These perspectives are essentially focused on three points of view: social and economic need, economic exploitation of outer space and / or national security issues. The first, the social and economic needs, is a vision focused on improving the lives of the inhabitants of the Earth. For example, at the time of the launch of Apollo 11, protesters showed up at the Kennedy Space Center to protest the sums invested in the program as human needs in terms of poverty and health persisted. These funds, if they are diverted, could contribute to the struggle to improve the human condition. The reality is that such a compromise will not happen: the poor and disadvantaged lack the political weight to win this battle.

| Manned spaceflight has no independent justification because, so far, all that is accomplished in space can be accomplished by robotic means. |

The economic exploitation of outer space is based on the principle that, from a low Earth orbit, many things become possible for commercial purposes. Communications and remote sensing, plus space navigation, were the first precursors of these efforts. These initial tasks did not require human presence, a fact that remains relevant to most space trading activities. Space tourism is the subject of much debate, but the practical issue of affordable and reliable access to and from space has delayed progress. In any case, this perspective minimizes the human exploration aspect of space activities.

Perhaps most importantly, the third point concerns the uses of space for security purposes, which are currently carried out by unprepared missions, with no apparent loss of efficiency. The fact is that each of these perspectives is not hostile to the exploration of the human space, but has a lower priority. As a result, resources in their opinion should move towards their priority.

The order in which each perspective appears is the result of the story of a specific state and its vision of itself. Their importance changes over time: nothing is static and a mixture of views appears and disappears depending on events. Thus, for China, national security was the initial driver, while in India, space activities of political necessity had to be linked to social and economic development. While both states have evolved since this initial period, the previous perspective has faded but is not disappearing.

The ultimate justification

Manned spaceflight has no independent justification because, so far, all that is accomplished in space can be accomplished by robotic means. The initial proposals for Earth-orbiting satellites, such as the Arthur C. Clarke article of 1945, had men on board to carry out the tasks currently carried out by the comsats and remote sensing systems. (The United States, at about the same time, rejected a proposed satellite in Earth orbit because it was not a weapon, so they had no military purpose.) These two functions do not need to be humans. In fact, human beings add enormous costs and other requirements simply to keep their lives aboard the spaceship. Humans can make a difference in space operations because of their ability to adapt to changing circumstances. All eventualities can not be solved remotely. The question is therefore, what justifies the human presence in a mission, given the high costs and additional support technologies.

| The harsh reality is that this mixture of sacred and profane advances American space exploration. |

In the short term, the rationale behind the exploration of the human space in the United States comes down to jobs, particularly constituent jobs. Other justifications embodied in the theme of human nature and the quest for the exploration of the unknown often touch the heart of their articulators, but do not constitute the critical factor. Space policy in the United States is a priority for some of the public or Congress. Linking the activities to the constituent jobs provides the additional political support necessary for the pursuit.

This link allows NASA to overcome its failures: Apollo 1, Challenger, Columbia and endless delays in the development of the Space Shuttle and Space Launch System (SLS). The approval of the shuttle program in 1972, the X-33 program in 1996 and the SLS in 2011 all relied on jobs, in California for the first two and more generally for the third. The big unknown is whether the first two would have been approved without this justification, given that both were during the presidential election years.

This reality does not deny other motivations, especially the concept of border or the more general human quest to understand the unknown. The harsh reality is that this mixture of sacred and profane advances American space exploration. The previous insult mocking the SLS as the "Senate Launch System" was a compliment of setbacks to the two Senators (Kay Bailey Hutchison of Texas and Bill Nelson of Florida) involved. They took the tools available to keep the exploration of the human space on the national agenda. Both are gone, but the program continues. Recent events have put SLS at risk, but NASA administrator Jim Bridenstine has reaffirmed the agency's commitment to SLS (see "Rethinking EM-1 and SLS," The Space Review , March 18, 2019.) He has no choice, given the political realities.

Note: We are temporarily moderating all under-committed comments to cope with an increase in spam.

[ad_2]

Source link