[ad_1]

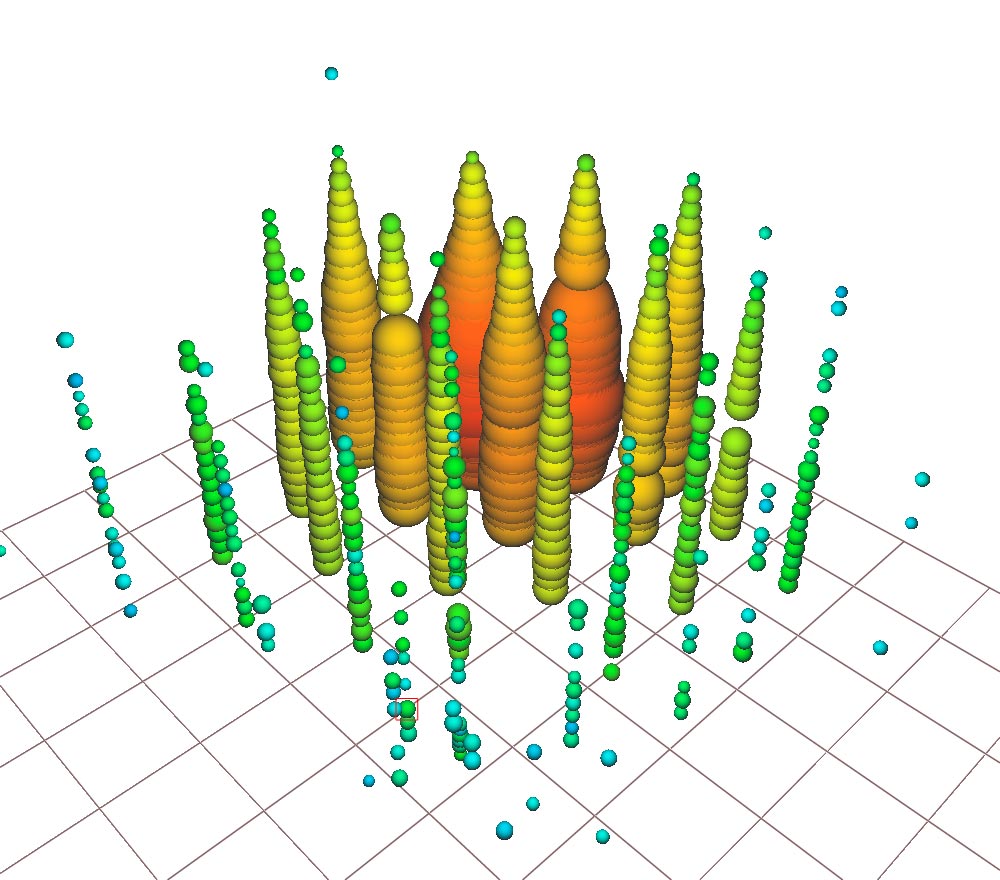

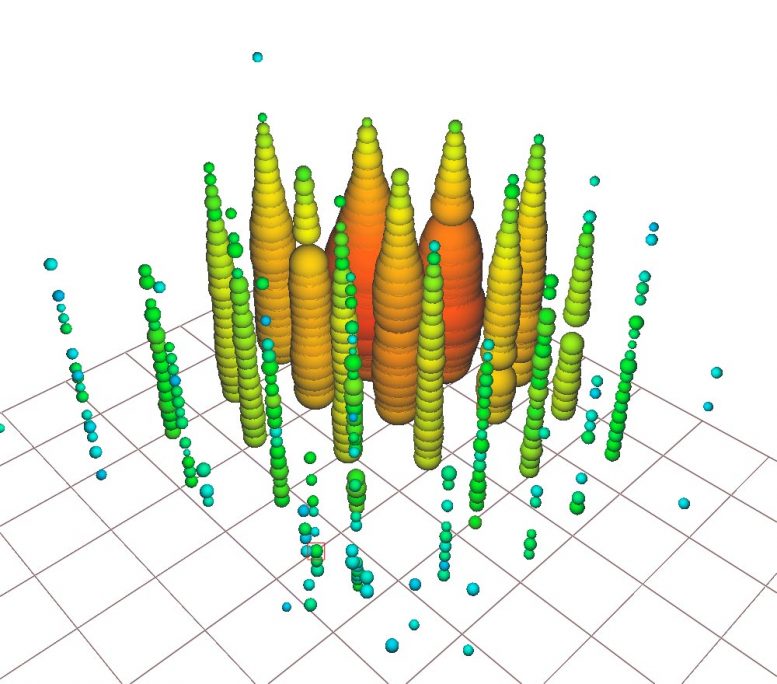

A visualization of the Glashow event recorded by the IceCube detector. Each colored circle shows an IceCube sensor that was triggered by the event; red circles indicate sensors triggered earlier in time and green-blue circles indicate sensors triggered later. This event has been nicknamed “Hydrangea”. Credit: IceCube Collaboration

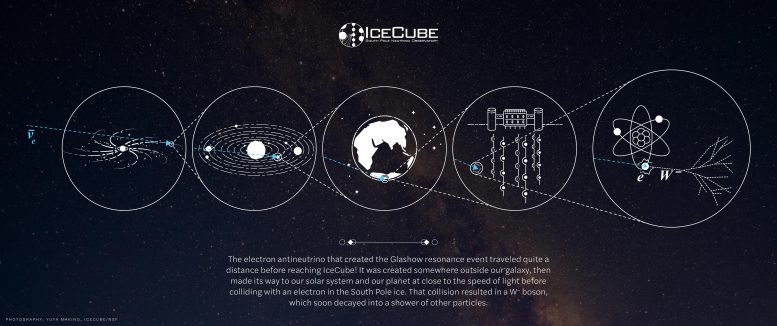

The South Pole neutrino detector saw a Glashow resonance event, a phenomenon predicted by Nobel Prize-winning physicist Sheldon Glashow in 1960, where an antineutrino electron and an electron interact to produce a W-boson.

On December 6, 2016, a high-energy particle called electronic antineutrino flew to Earth from space at a speed close to the speed of light carrying 6.3 petaelectronvolts (PeV) of energy. Deep inside the ice cap at the South Pole, it shattered into an electron and produced a particle that quickly disintegrated into a shower of secondary particles. The interaction was captured by a massive telescope buried in the Antarctic glacier, the IceCube Neutrino Observatory.

“We can now detect individual neutrino events that are unmistakably extraterrestrial in origin.” – Christian haack

IceCube had seen a Glashow resonance event, a phenomenon predicted by Nobel Prize-winning physicist Sheldon Glashow in 1960. With this detection, scientists provided further confirmation of the Standard Model of particle physics. He also demonstrated the ability of IceCube, which detects nearly massless particles called neutrinos using thousands of sensors embedded in Antarctic ice, to do fundamental physics. The result was published today (March 10, 2021) in Nature.

Sheldon Glashow first proposed this resonance in 1960, when he was a postdoctoral researcher at what is now the Niels Bohr Institute in Copenhagen, Denmark. There he wrote an article in which he predicted that an antineutrino (the antimatter twin of a neutrino) could interact with an electron to produce a yet unknown particle – if the antineutrino had only the right energy – through a process known as resonance.

When the proposed particle, the W– boson, was finally discovered in 1983, it turned out to be much heavier than what Glashow and his colleagues predicted in 1960. The Glashow resonance would require a neutrino with an energy of 6.3 PeV, almost 1000 times more energetic than what CERNThe Large Hadron Collider is capable of producing. In fact, no artificial particle accelerator on Earth, present or planned, could create a neutrino with so much energy.

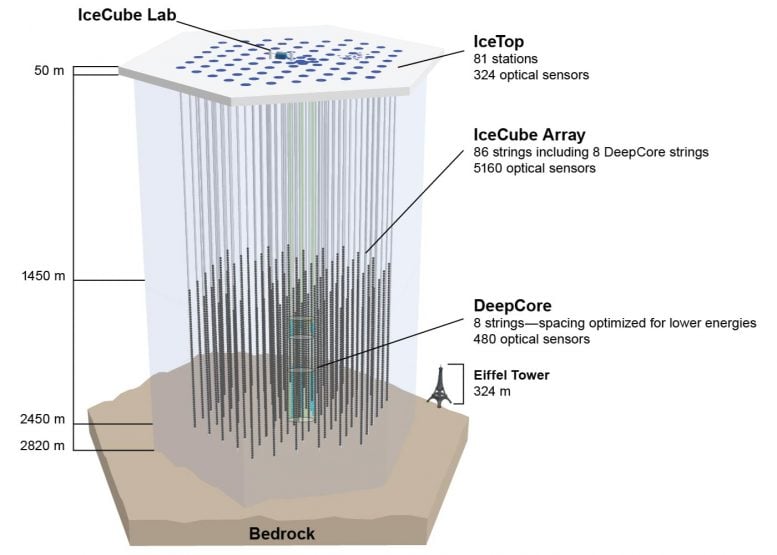

A schematic of the in-ice portion of IceCube, which includes 86 strings containing 5,160 light sensors arranged in a three-dimensional hexagonal grid. Credit: IceCube Collaboration

But what about a Natural accelerator – in space? The enormous energies of supermassive black holes in the center of galaxies and other extreme cosmic events can generate particles with energies impossible to create on Earth. Such a phenomenon was probably responsible for the antineutrino 6.3 PeV which reached IceCube in 2016.

“When Glashow was a post-doctoral fellow at Niels Bohr, he could never have imagined that his unconventional proposal to produce the W– The boson would be produced by an antineutrino from a distant galaxy crashing into the Antarctic ice, ”says Francis Halzen, professor of physics at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, headquarters of IceCube maintenance and operations, and senior research scientist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. ‘IceCube.

Since IceCube began fully functioning in May 2011, the observatory has detected hundreds of high-energy astrophysical neutrinos and produced a number of significant results in particle astrophysics, including the discovery of an astrophysical neutrino flux. in 2013 and the first identification of an astrophysical neutrino source in 2018. But the Glashow resonance event is particularly noteworthy because of its remarkably high energy; this is only the third event detected by IceCube with an energy greater than 5 PeV.

“This result proves the feasibility of neutrino astronomy – and the ability of IceCube to do so – which will play an important role in the future physics of multi-messenger astroparticles,” says Christian Haack, who was a graduate student at RWTH Aachen while working on this analysis. “We can now detect individual neutrino events that are unmistakably extraterrestrial in origin.”

The electronic antineutrino that created the Glashow resonance event traveled quite a distance before reaching IceCube. This graph shows his background; the blue dotted line is the path of the antineutrino. (Not to scale.) Credit: IceCube Collaboration

The result also opens a new chapter in neutrino astronomy as it begins to disentangle neutrinos from antineutrinos. “As the previous measurements were not sensitive to the difference between neutrinos and antineutrinos, this result is the first direct measurement of an antineutrino component of the astrophysical neutrino flux,” explains Lu Lu, one of the main analyzers of this article, who was a postdoc at Chiba University in Japan during the analysis.

“There are a number of properties of astrophysical neutrino sources that we cannot measure, such as the physical size of the accelerator and the strength of the magnetic field in the acceleration region,” says Tianlu Yuan, scientific assistant at Wisconsin IceCube Particle Astrophysics Center. and another main analyzer. “If we can determine the neutrino-antineutrino ratio, we can directly study these properties.”

To confirm the detection and make a decisive measurement of the neutrino-antineutrino ratio, the IceCube collaboration wants to see more Glashow resonances. A proposed extension of the IceCube detector, IceCube-Gen2, would allow scientists to perform such measurements in statistically significant ways. The collaboration recently announced a detector upgrade that will be implemented over the next few years, the first step towards IceCube-Gen2.

Glashow, now professor emeritus of physics at Boston University, echoes the need for more detections of Glashow resonance events. “To be absolutely sure, we should see another event like this at the same energy as the one that was seen,” he said. “So far there is one, and someday there will be more.”

Finally, the result demonstrates the value of international collaboration. IceCube is operated by more than 400 scientists, engineers and staff from 53 institutions in 12 countries, together known as the IceCube Collaboration. The main reviewers for this article worked together in Asia, North America, and Europe.

“The detection of this event is another ‘first’, once again demonstrating IceCube’s ability to deliver unique and exceptional results,” says Olga Botner, professor of physics at Uppsala University in Sweden and former spokesperson for the IceCube collaboration.

“IceCube is a wonderful project. In just a few years of operation, the detector discovered what it had been funded to discover: the most energetic cosmic neutrinos, their potential source in blazars, and their ability to aid in multi-messenger astrophysics, ”says Vladimir Papitashvili, program manager in the Office of Polar Programs at the National Science Foundation, IceCube’s main funder. James Whitmore, program manager in the NSF Physics Division, adds: “Now IceCube amazes scientists with a rich source of new treasures that even theorists never expected to find so soon.”

Reference: “Detection of a shower of particles at the Glashow resonance with IceCube” March 10, 2021, Nature.

DOI: 10.1038 / s41586-021-03256-1

The IceCube Neutrino Observatory is funded primarily by the National Science Foundation (OPP-1600823 and PHY-1913607) and is headquartered at the Wisconsin IceCube Particle Astrophysics Center, a UW-Madison research center in the United States. IceCube’s research efforts, including critical contributions to the operation of the detector, are funded by agencies in Australia, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Germany, Japan, New Zealand, Republic of Korea , Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom and the United States. The construction of IceCube was also financed with significant contributions from the National Fund for Scientific Research (FNRS & FWO) in Belgium; the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) and the German Research Foundation (DFG) in Germany; the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation, the Swedish Polar Research Secretariat and the Swedish Research Council in Sweden; and the University of Wisconsin-Madison Research Fund in the United States

[ad_2]

Source link