[ad_1]

Many of us will recognize Daniel Gilbert as a retirement fund spokesperson, helping us see how long our retirement funds will last with dominoes, ribbons and sticky notes. But his real job is to be a professor of psychology, and he recently co-wrote a short but hard-hitting article in Science on another bias in our judgments. When we describe aspects of the world, large or small, rare or numerous, we compare what we see with a relevant reference value. When we think of the frequency with which something happens, our memory of its former frequency influences our judgment – psychologists call this change of concept induced by prevalence. The study reports seven simple experiments

The Study

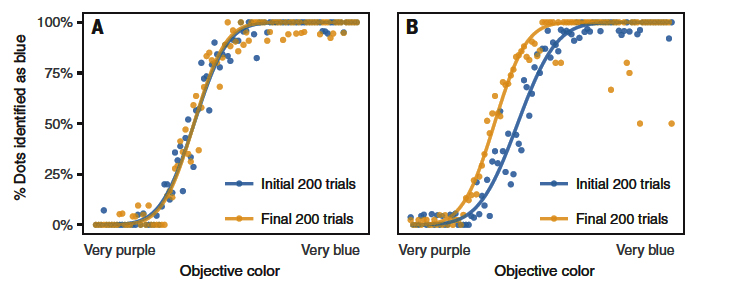

In the first study, people showed colored dots ranging from very violet to very blue and asked to identify blue dots carefully. For the control group, the prevalence of blue dots did not change; for the subjects tested, the number of blue dots decreased. Here is the graph of their determinations in the first and last 200 trials out of 1000.

In control group A, where the frequency of blue dots was constant, the identification of "true blue" from others shades of blue did not change. But for those in the test group, B, where there were fewer "true blue" points in the final tests, participants began to see other shades like purple as blue. In essence, as the prevalence of blue dots decreased, the definition of blue was widened. Prevalence affected our judgment. And they showed the same effect when the test subjects were told that the prevalence would decrease or that they would be told to be consistent in their decisions and that they would receive a monetary reward, and when the prevalence would be reduced slowly or abruptly. In fact, they showed the counterfactual, when the prevalence of blue dots increased, the criteria for which was narrowed of blue. They repeated the experiment using threatening faces and descriptions of unethical behavior instead of blue dots and again prevalence decreased the expanded criteria for that faces and behaviors previously considered OK are no longer perceived as such. change makes us more pessimistic

The implications are enormous. This helps explain why despite extraordinary progress in treating the disease and reducing poverty, we still believe that a crisis worsens. Our pessimism may be rooted in what Dr. Gilbert shows with these blue dots, as our criteria change with prevalence. This helps explain why Hans Rosling's message in Factfulness, that the world can simultaneously be both better and bad, is ignored even when it's true most of the time

More importantly, the pessimism that promotes perceptual bias prevents us from recognizing our success and continuing to argue in the same strident tones. We continue to fight against increasingly conflictual battles by focusing our attention on topics that were not of concern a few years ago. In the United States, air pollution battles have shifted from cars to household products and cosmetics; for smoking, despite a reduction of 42.4% in 1975 to 15.5% last year, the media talk concerns vaping.

Recalibration – An Example

The Royal Observatory, located in Greenwich, United Kingdom, was established almost 350 years ago and houses two meridians, the Meridian and the Reference Point. Greenwich meridian time. the history of time and space. Due to increasing light pollution as well as pollution from industrialization, the observatory closed in 1957.

Because the air is much cleaner today, Sixty years ago, he reopens, the telescopes return to work [1] scheduled for July 27 . It's worth taking a moment to enjoy our victories. It is also worth asking whether the bias described by Dr. Gilbert so eloquently distorts our public conversations.

[1] A blood moon occurs when the full moon pbades through the shadow of the earth.

Sources: First, we must start with Marginal Revolution, Tyler Cowen's curatorship and his articles on economics, but much more, which has indicated to me the work of Dr. Gilbert. That led me to his article, Change of Concept Induced by Prevalence in Human Judgment published in Science DOI: 10.1126 / science.aap8731. The notes on the Royal Observatory come from Atlas Obscura.

Source link