[ad_1]

Glioblastoma is a type of brain cancer that was recently very visible in the media after Senator John McCain was treated for it. Glioblastoma has claimed more than 15,000 lives in 2015. However, researchers at Duke University are working to reduce this number through "oncolytic viral therapy" of an unexpected medical foe: the poliovirus .

What is Oncolytic Cancer Therapy?

It is a type of treatment of a cancer branch called immunotherapy where human viruses, which can fight cancer in different ways, are modified in the laboratory and used to fight cancer. With oncolytic viral therapy, viruses can stimulate the immune system, the same system that fights disease like the flu, to attack cancer as well. With this particular form of therapy, viruses can also infect the cancer cells themselves, causing them to break down and die.

Viral therapy came into existence many years ago when spontaneous tumor remissions occurred after immunizations with weakened live viruses. There have been studies using viral therapy in lung cancer and melanoma, with a real viral therapy approved for melanoma by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2016.

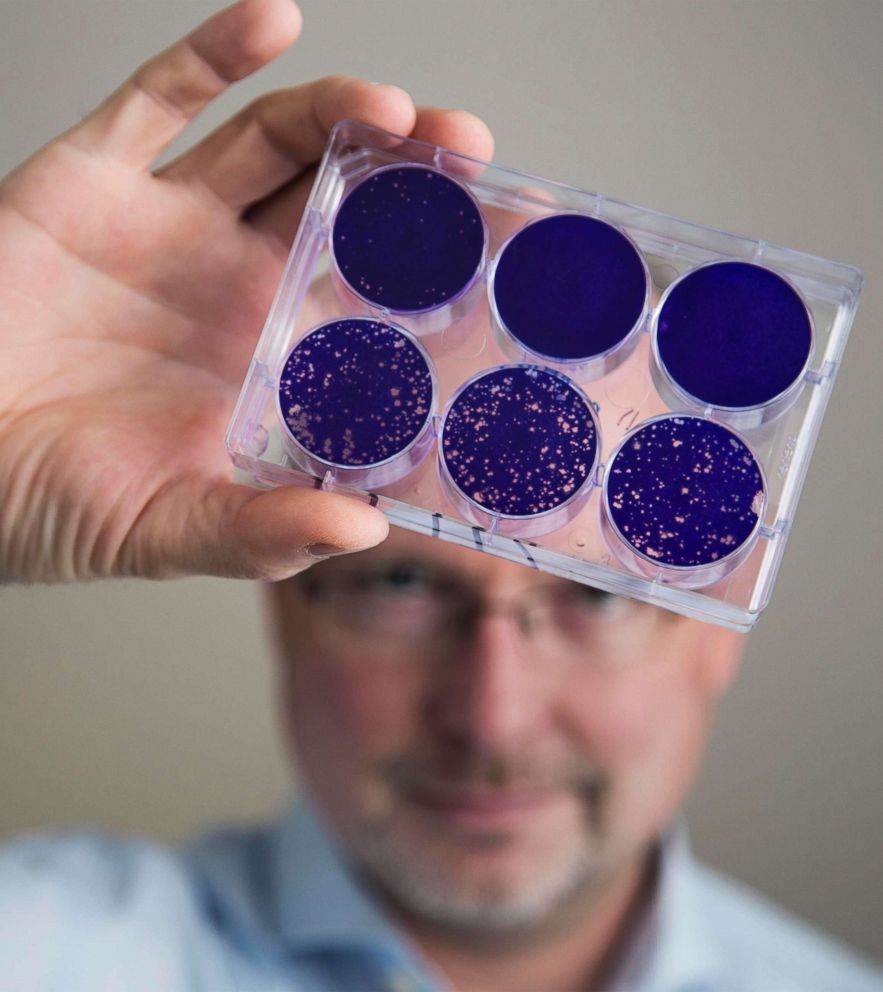

Shawn Rocco / Duke Health via AP

Shawn Rocco / Duke Health via AP this brain cancer?

Brain cancers are rare, but if someone develops brain cancer, it is likely to be a glioblastoma. Unfortunately, his prognosis is bleak, with most patients dying about 14 months after diagnosis.

This is not only because of a strong tendency to malignancy, but also because of its resistance to current cancer treatments: surgery, radiotherapy and chemotherapy.

The reality of the prognosis of glioblastoma has led some patients to choose to end their lives shortly after diagnosis. New treatments are desperately needed, and this particular type of cancer has features that make it an ideal candidate for viral therapy.

How does all this work?

A live poliovirus is used, weakened by a process in the laboratory. It is important to note that live and debilitated viruses have been commonplace for years and are critical components of many vaccines around the world, such as poliovirus.

In the case of oncolytic viral therapy, poliovirus is genetically modified so that it functions as its regular viral ego but does not have the capacity to cause its "normal" disease. The part of the poliovirus that causes the disease, infamous for causing a devastating neurological disease, is removed and replaced with a harmless part.

For the immune system, it looks like "real polio" but does not have the ability to cause disease, or even mutate to anything that could cause it. This is important because the modified virus must maintain the ability to affect the same target, the brain.

The virus is also modified to include components that would stimulate the immune system to defend itself. Patients with glioblastoma often have poorly functioning immune systems, both from the disease and also from treatments such as radiation that knock out immunity. By inserting a new segment into the virus, as in the cold, the immune system becomes active without any disease. A strong reaction of the immune system attracts the cells to the cancer to attack it.

Because cancer cells function differently than normal cells, the genetically modified virus interacts differently with cancer and non-cancer cells. Cancer cells of glioblastoma have different chemical components than non-cancerous brain cells. The genetically modified poliovirus thus has the ability to target cancer cells, infect and take over the machines of the cell, and encourage a person's own immune system to attack. It does this by leaving the non-cancer cells intact.

Shawn Rocco / Duke Health by AP

Shawn Rocco / Duke Health by AP Why use poliovirus?

Human viruses are unique, co-evolved with the human immune system, teaching it to recognize and kill infected and abnormal cells. The poliovirus has a large size of RNA (RNA is a genetic component), compared with other viruses, so that researchers can play with its parts in genetic manipulation. It also has a limited life span in humans, unlike other viruses, such as chicken pox. Thus, it has the potential to be used to treat a number of different types of cancers.

What were some of the results?

Using polio as a "cancer killing virus," Duke researchers have seen a three-year survival rate of about 21% in brain cancer patients who have the oncolytic virus. survival was only 4% among those who had not received treatment.

Therapy could be administered locally in the tumor site of the brain through a special catheter. This allows more "sowing" of the virus into the tumor cells and does not spread throughout the body. Many patients have been able to tolerate poliovirus treatment well, but some have had side effects such as seizures, headaches, and speech problems. Too much inflammatory response can be a bad thing. Higher doses of poliovirus treatment have been badociated with more brain inflammation. The researchers worked on dosing and reducing inflammation without compromising the immune system using bevacizumab, a drug that minimizes inflammation during viral treatment.

Poliovirus treatment is still undergoing clinical trials and is not yet ready for the general public. The big questions are the potential cost, as some current viral therapies cost about $ 60,000 per treatment and the ability of hospitals to transport, store and discard these drugs is of concern to patients and providers.

Where can we learn more?

Immunotherapy is still a developing field. Talking to a health professional and tracking the results of quality sources, such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the American Cancer Society, are important ways to find out more.

Petrina Craine is a resident physician in emergency medicine in Oakland, California, working in the ABC News Medical Unit.

Source link