[ad_1]

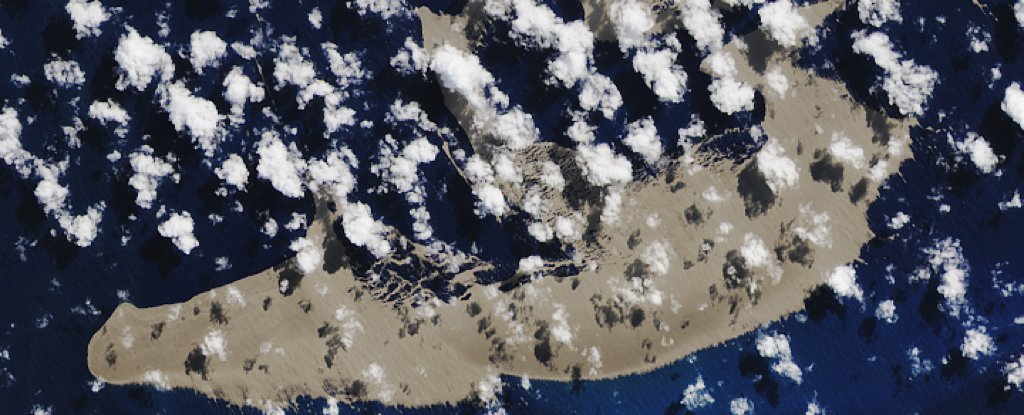

A gigantic fleet of floating rocks, spewed out of an underwater volcano in the Pacific Ocean, floated through the waves for thousands of kilometers. Eventually, he made it all the way to Australia, then started a new project: revitalizing the world’s largest (and critically endangered) coral reef system.

This chain of unlikely events might sound somewhat unbelievable, but it’s an entirely true story – one that has unfolded in dramatic fashion over the past year, while also highlighting the surprising and largely unseen ways in which Earth’s natural environmental systems intersect.

Stranger still, this isn’t the first time this has happened. A 2001 eruption of the same seamount – an unnamed volcano, simply dubbed Volcan F or 0403-091, located near the Vava’u Islands in Tonga – produced a similar rock flotilla, which also traveled on currents to Australia over the course of a year.

When this phenomenon occurs, it creates what is called a pumice raft – a floating platform made up of countless pieces of floating, very porous volcanic rock.

Each of these small rocks attracts marine organisms including algae, barnacles, corals, etc. These tiny travelers end up hitchhiking across the ocean, and they can help seed and replenish endangered coral systems at their ultimate destination: for many, the Great Barrier Reef.

“Each piece of pumice stone has its own little community that was transported across the oceans of the world – and we had billions of pieces of that pumice stone floating there after the eruption,” says geologist Scott Bryan of Queensland University of Technology in Australia.

“Each piece of pumice stone is a home and a vehicle for an organization, and that’s just great. The sheer number of individuals and this diversity of species being transported thousands of kilometers in just a few months is truly quite phenomenal.

Bryan knows a thing or two about those pumice migrations. He has been studying volcanic rafts for 20 years, investigating the 2001 eruption, its 2019 successor (which started washing up off the Australian coast in April) and other underwater eruptions.

Its most recent study, published last month, looked at the 2012 eruption of the Le Havre seamount, also in the South Pacific – considered the largest underwater volcanic eruption on record, which is broadly equivalent to the most powerful volcanic eruption on earth in the 20th century.

This event produced a gigantic raft of pumice that ended up scattering over an area twice the size of New Zealand – in addition to littering the seabed with giant pieces of pumice the size of a van. .

Geologist Scott Bryan with a pumice stone. (QUT)

Geologist Scott Bryan with a pumice stone. (QUT)

“We don’t understand why some pumice stones sink during the eruption in place and others can float for many months and years on the world’s oceans,” Bryan says, but further analysis could fill in the gaps.

“This will help us understand the mechanisms and dynamics of these explosive eruptions and better understand why these eruptions produce potentially dangerous pumice rafts.”

Potentially dangerous, that’s right. Last year’s eruption of Volcano F produced a stunning video of what it feels like to navigate these gargantuan rafts, which look like giant slicks of oil, made only of swaying rocks that seem to go on forever.

These surreal floating formations are not inherently dangerous in themselves, but they could potentially damage boats and suffocate coasts in certain circumstances, as another video from this year attests.

For now, however, researchers are hoping that the latest shipment from Volcano F will do some good to the Great Barrier Reef off the coast of Australia, which is besieged by bleaching corals as the world’s oceans warm due to of climate change.

While the organisms carried in the rock flotilla can help replenish reef ecosystems, scientists are keen to stress that they are not a quick fix.

“Pumice rafts alone will not directly help mitigate the effects of climate change on the Great Barrier Reef,” says Bryan.

“This is a boost of new recruits, new corals and other reef-building organisms, which occurs every five years or so. It’s almost like a vitamin injection for the Great Barrier Reef. . “

And maybe much further as well. The 2019 pumice raft – which a year ago measured around 20,000 football pitches – now sits all along Australia’s east coast from Townsville in north Queensland to north New South Wales: sprawling on more than 1300 kilometers of coastline.

It is a massive dispersion, resulting from a single event far beyond the horizon, and which serves to remind us of the links between what perhaps seem only disparate marine ecosystems.

“This shows that the Great Barrier Reef is connected to coral reefs located thousands of miles further east,” says Bryan.

“In terms of the health of the Great Barrier Reef, it is also important that these remote reefs are taken care of.”

Geologist Scott Bryan examines the pumice stones. (QUT)

Geologist Scott Bryan examines the pumice stones. (QUT)

As for the Volcano F, it has raised its profile in recent years, and in more ways than one. The ongoing eruptions are not only attracting the attention of scientists – they are also changing and building the underwater landscape around the volcano.

Bryan was part of an expedition team that inspected the site this year, collecting samples and observing what the volcano looks like under the waves.

“It’s a volcano that’s about to break through the surface and will become an island in the years to come,” Bryan says.

We’ve seen what it can look like in other parts of the world, and it makes for a pretty incredible sight: instead of gigantic volcanic rafts, entire pop-up islands emerge from the ocean.

Volcano F was already a great story, but it looks like the next chapter is even more amazing.

[ad_2]

Source link