[ad_1]

During the briefings, the president questioned his team about how they could have misjudged the time it would take for the Afghan army to collapse, according to people familiar with the matter. He also expressed dismay at the failure of Ashraf Ghani, the ousted Afghan president who fled the country on Sunday, to adhere to a plan he presented in the Oval Office in June to prevent the Taliban from s seize large cities.

Throughout the weekend, Biden had remained in presidential retirement, receiving briefings on screens or over the phone while sitting alone at a conference table. The advisers met separately to discuss when and how he should deal with the situation. When he returned to the White House at noon on Monday, many of his aides assumed he would at least be spending the night.

As advisers worked feverishly on Monday to calibrate the president’s speech, there was far less concern about predictable criticism from Republicans than about how Biden’s own words and calculations over the past few months had been so wrong. The episode highlights two of Biden’s strongest political traits: a stubborn defensive streak and a fierce certainty in his decision-making that leaves little room for questioning.

Scenes in Kabul are “much worse than those in Saigon”

Inside the White House and national security agencies, there has been a fierce debate about how the current disaster unfolding in Afghanistan happened. Officials who have built entire careers on issues related to the country have struggled to comprehend the abrupt end of the 20-year conflict.

But the provocative message from Biden’s speech on Monday mirrored conversations he had had with advisers over the past 48 hours. Officials were aware that the situation that ultimately unfolded was possible – with the Taliban crushing the civilian government in Kabul after US forces left – but had hoped it was unlikely.

Key Biden associates have been outspoken this week in admitting they didn’t expect it to happen so quickly.

“Certainly the speed at which cities have fallen has been much faster than expected,” Sullivan said Monday on NBC’s “Today”.

At the same time, Biden has been confronted with his own past statements downplaying the idea that the Taliban would invade Kabul and flatly rejecting the prospect of evacuating the US embassy there.

Yet in retrospect, Biden’s comments on the end of the war – including a dismissal of comparisons to the fall of Saigon in 1975 – seemed very misguided.

“For the administration to say it won’t be Saigon as we look at those kind of pictures – well maybe they’re right. Because they’re a lot worse than Saigon,” Ryan Crocker said, who served as Afghanistan’s ambassador under former President Barack Obama.

Questions left unanswered

Biden has long exuded assurance both in his views on foreign policy and in his political strategy, honed during his many years in Washington. Aides says that while he welcomes dissenting opinions and vigorous debate, he is most likely to abruptly end a conversation if he feels his knowledge of a situation – especially on international affairs – is being challenged. question.

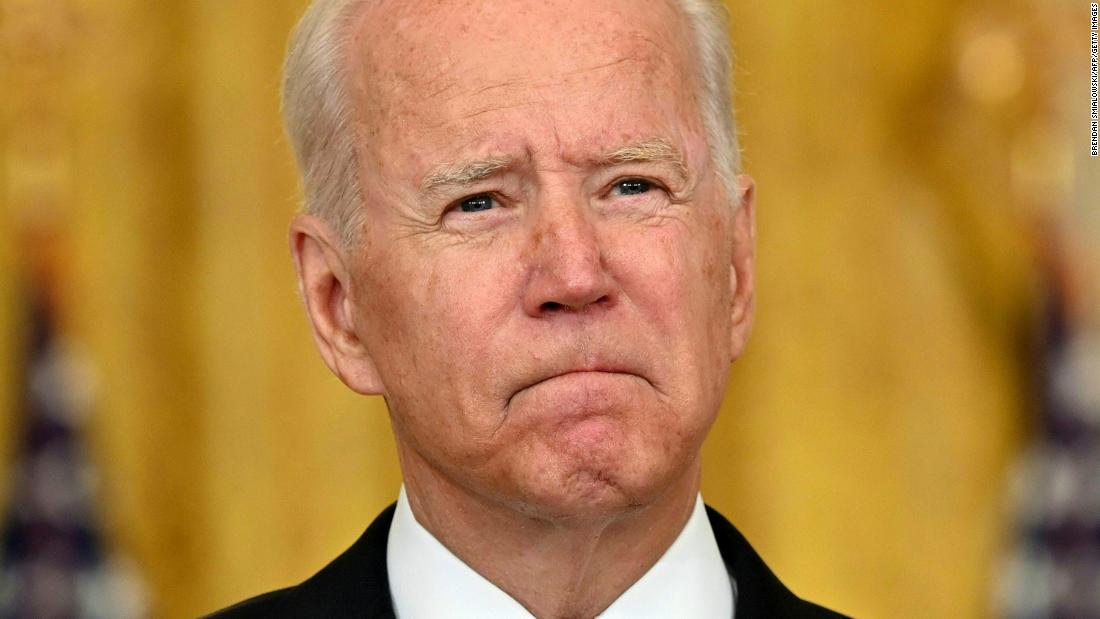

This stubbornness was fully manifested in his speech from the East Room, in which the president spent a great deal of time defending his decision to withdraw US troops rather than acknowledging his administration’s admitted miscalculations. While briefly acknowledging that the Taliban’s advance and the fall of the government came “faster than expected,” Biden made it clear that his intention to end the war had not changed.

“I am the President of the United States of America,” Biden said. “The male stops with me.”

Yet if that is really the case, Biden left unanswered a myriad of questions about how events got out of hand so quickly, only claiming that the process of withdrawing the troops had been “difficult and messy.”

He has shown no sign – publicly or, according to his aides, in private – that he believes his own decision to withdraw troops from Afghanistan has helped provoke the current crisis. Instead, he blamed elsewhere: the Afghan army for collapsing, former President Donald Trump for agreeing to a deal with the Taliban and his predecessors to expand a mission in a country without any consideration of how to end it.

He strongly attacked Ghani, saying the Afghan leader “categorically refused” Biden’s advice on seeking a political settlement with the Taliban and that he was wrong about the strength of the Afghan army.

“I know my decision will be criticized, but I would rather accept all of this criticism rather than pass this decision on to another president of the United States,” he said in his speech.

As he walked out of the East Room without answering questions from reporters, key members of Congress signaled their intention to get to the bottom of the crisis.

Senator Mark Warner of Virginia, Democratic Chairman of the Intelligence Committee, said he and other lawmakers had “difficult but necessary questions about why we were not better prepared for a worst-case scenario involving a also rapid and total collapse of the Afghan government and security forces. “

“We owe these answers to the American people,” said Warner, “and to all who have served and sacrificed so much.”

Double

“No one disagrees with the decision to leave Afghanistan – literally almost no one,” a former Obama national security official told CNN on Monday. “But carrying out this decision was their responsibility and they were caught off guard.”

In the White House, few advisers are closer to Biden than Secretary of State Antony Blinken and National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan, both of whom have spent years working for him. They appeared on TV this week to defend their boss’s decision to end the war.

Other advisers, including Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin and Joint Chiefs Chairman Gen. Mark Milley, have spent less time in Biden’s orbit. When the president weighed in on Afghanistan in the spring, Milley was among the loudest voices arguing for a continued presence of US forces in Afghanistan.

Biden rejected this view, even as generals warned of the potential for a Taliban takeover. Whether it’s a miscalculation, intelligence failure, or a combination of the two, the President now faces a credibility crisis on one of his strongest business cards: foreign policy.

“You cannot defend the execution here,” said David Axelrod, a senior Obama adviser who participated in the Afghanistan deliberations early in this administration. “It’s been a disaster and everyone – anyone with a beating heart – watching these scenes of people swarming desperately in the airport trying to get out before the slaughter they anticipate from the Taliban, you know , it’s heartbreaking. It’s depressing. And it’s a failure. “

“He has to take responsibility for this failure,” said Axelrod, who is a senior political commentator for CNN. “He’s the commander-in-chief.

Officials say the president’s thinking is driven by the belief that, like him, most Americans are tired of the protracted conflict in Afghanistan. His advisers have been convinced in recent months that the American public is behind them in their decision to withdraw American troops from Afghanistan.

Some White House officials have also privately noted that as the country continues to fight Covid-19 and the economy ignores the lingering effects of the pandemic, events unfolding thousands of miles away are hardly at the forefront of the minds of Americans.

[ad_2]

Source link