[ad_1]

During a hearing on the 1937 law effectively banning cannabis across the United States, a Congressman asked Harry Anslinger, Commissioner of the Federal Office of Addiction, "if the drug addict was taking drugs to become a heroin user , opium or cocaine ", then accused marijuana for inspiring explosions of vicious and irrational violence, said he had found no evidence of the progression of its users to other drugs. "I have not heard of a case like this," he said. "I think it's a totally different class. The marijuana addict is not going in that direction. "

By the early 1950s, Anslinger had changed his mind. "More than 50% of young people [heroin] drug addicts started to smoke marijuana, "he said. told a congressional committee in 1951. "They started there and went to heroin; they took the needle when the thrill of marijuana was gone. "

Anslinger reiterated this point four years later, when he testified in favor of tougher penalties for marijuana-related offenses. "While we are discussing marijuana," said one senator, "the real danger is that marijuana use ultimately causes many people to consume heroin." Anslinger D & # 39; agreement"This is the big problem and our big concern about the use of marijuana, which eventually leads to heroin addiction, if it is consumed over a long period."

The idea that marijuana use "leads to" heroin use, possibly known as "stepping stone" or "gateway" theory, has become a lasting theme of anti-war propaganda. pot, which we can still hear the echoes today. As Vice President, Joe Biden, currently principal candidate for the Democratic nomination for the presidency, m said "I think legalization is a mistake" because "I still believe it's an introductory drug." A few years ago, before come around on legalization, the governor of New York, Andrew Cuomo, concerned that "marijuana leads to other drugs, and there is a lot of evidence that's the truth."

Was Cuomo right about it? Was Anslinger on something when he warned that the pot smoker today is the heroin addict of tomorrow?

Anslinger was right to say that people who use marijuana are more likely than those who do not try to use heroin. But the nature of the relationship between cannabis use and "harder" drug use remains controversial: does marijuana use lead to opioid use and, if so, in what way? meaning? Can the association be explained by factors that independently predispose people to use both types of drugs?

These issues are of additional importance given the current collapse of marijuana prohibition in the United States, an evolution that coincided with a thrust in opioid-related deaths. However, despite the superficial appeal of linking these two trends, the evidence suggests that the legalization of marijuana does not cause an increase in opioid-related harm and may actually reduce it.

Clear correlations, contested causes

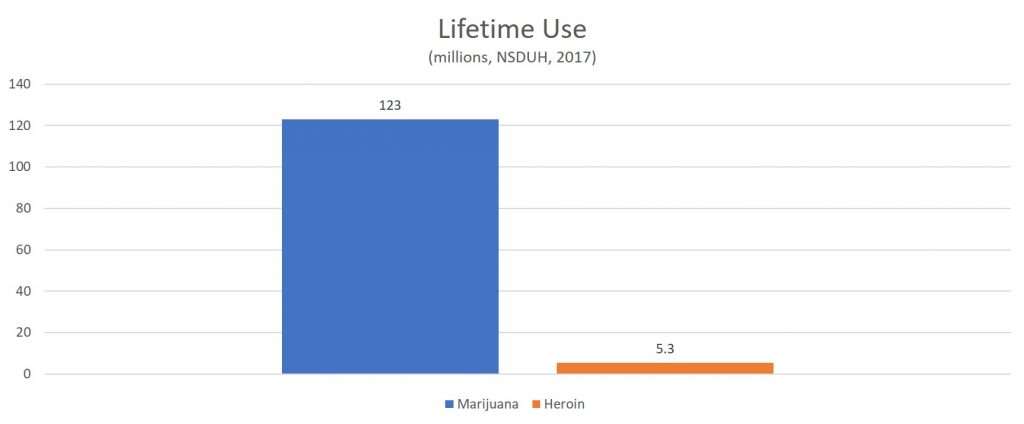

It is clearly not true that marijuana use leads inexorably to heroin use, as Anslinger has sometimes suggested. Recent data From the national survey on drug use and health indicate that 123 million Americans have tried marijuana, while 5.3 million have tried heroin. In other words, marijuana use is 20 times more common than heroin and less than 5% of cannabis users have tried heroin.

It is true though that people who use "hard drugs" such as heroin usually used marijuana first. In a group of about 1,200 New Yorkers followed from high school to mid-thirties, for example, about 95 percent subjects who had used illicit drugs other than marijuana started with cannabis.

It is also true that people who use marijuana are more likely than those who do not subsequently use other illicit drugs. in the study Among New Yorkers, men who had used marijuana before the age of 20 without having used it the previous year were almost five times more likely than men who did not use marijuana before age 20 without having used it the previous year. had never used marijuana to report using other illicit drugs. The corresponding risk ratio for men who had been using marijuana daily during the previous year was 12: 1. The association between cannabis use and other illicit drugs is particularly high users of marijuana and people who start using them very early.

A 2013 Analysis Data from the National Survey of Drug Use and Health revealed that young men and women who had used marijuana were two and a half times more likely to report the illegal use of drugs. # 39; opioids prescription. A 2017 Analysis Data from the national epidemiological survey on alcohol and related conditions revealed a similar risk ratio after adjusting for several potential confounding factors.

Although these correlations are clear, their meaning is not. One of the possible explanations is that marijuana use further encourages people to try other illicit drugs. Another possible explanation is that people who use marijuana are different from those who do not, in a way that also influences their likelihood of using other drugs. Pre-existing differences in genetics, personality and environment may explain both trends.

Psychologist Andrew Morral and his colleagues at the RAND Drug Policy Research Center have shown that an underlying propensity to drug use, combined with the relative availability of different intoxicants, could fully explain drug use. three phenomena highlighted by proponents of bridge theory: 1) that people tend to use marijuana before other illicit drugs, 2) that marijuana users are more likely to use other illicit drugs and 3) that the probability of progression increases with the frequency of marijuana use. Their mathematical model did not refute the bridge theory, but it proved that bridge theory is not necessary to explain these observations. Morral et al. concluded that "the available evidence does not favor the bridging effect of marijuana over the alternative hypothesis that marijuana and hard drug use is correlated because both are influenced by the heterogeneous responsibilities of individuals with respect to marijuana. 'drug test'.

Twins and Rats

Several studies have attempted to test the bridge theory by taking into account other variables that may be associated independently with drug use. A longitudinal study For example, New Zealand adolescents and young adults have found a strong association between the frequency of cannabis use and the use of other illicit drugs after adjusting for almost three dozen potential confounders. But like Morral et al. As pointed out, even such considerable efforts to control confounding factors are unlikely to do so perfectly. They calculated that, when the adjustment for confusion "does not account for only 2% of the variance in the propensity to use drugs," "marijuana users" appear to be likely to create hard drugs twice as important as non-users of marijuana. " It is therefore hardly surprising that controlling these covariates does not eliminate the association between marijuana and the use of hard drugs. "

Another approach examines this association in twins, who share the same family environment and have similar genes or, in the case of identical monozygotic pairs. A Australian study found that in cases where one twin had used marijuana before the age of 17 and the other no, the first twin was twice as likely to consume opioids, whether the twins were identical or fraternal and even after adjusting for several potential confounders. A similar study based on Register of Vietnamese Era found that people who had used marijuana before they were 18 were almost three times more likely to use opioids than twins who did not. In one study of Dutch twinsthe risk ratios were higher: subjects who had used marijuana at age 17 or younger were more than 16 times more likely than their co-twins to report "hard drug" use, for example.

Even these seemingly convincing results do not rule out the possibility that pre-existing differences may explain the associations. Regardless of the situational factors explaining why one twin uses marijuana as a minor and the other does not, it may also explain why one uses opioids and the other does not. "The observation that family factors do not fully explain the link between early cannabis use and the [drug] consumption, while suggesting a potential causal role of cannabis use in the development of other illicit drugs, does not prove such an association, "noted the authors of the Dutch study. "There may be other factors, including aspects of the non-shared environment (for example, peer affiliations) prior to the onset of cannabis use, which may explain the associations observed. . "

In addition to the usual problems of extrapolating animal behavior in the laboratory to human behavior in the real world, the relevance of research on rats is unclear. Even if early exposure to marijuana encouraged more people to consume heroin, it would not explain their willingness to try it. To the extent that the gateway theory focuses on the transition from cannabis use to the experimentation of other drugs, the sensitization looks like a red clutter.

What is the problem with Japan?

Variations in drug use patterns from one generation to another and from one culture to another suggest that marijuana's role as an entry drug depends on social norms and the status of the drug. black market rather than its intrinsic properties.

A Analysis 2001 National Household Survey data on drug abuse have shown that the likelihood of switching to "hard" drugs such as cocaine and heroin after consuming marijuana is 9% of those born in 1940 to 39% of those born in the early 1990s fell to 24% of those born in the early 1970s and 6% of those born in the late 1970s. concluded that "the gateway phenomenon reflects the norms prevailing among young people at a specific place and time", which means that "the links between the stadiums are far from being causal". As a result, "the mere act of restricting young people's access to drugs does not necessarily reduce the subsequent abuse of hard drugs."

A 2010 study reviewed data on the progression of drug use in 17 countries from the World Health Organization's World Mental Health Surveys. Subjects in most countries followed the pattern commonly seen in the United States, starting with alcohol or tobacco, and then progressing to marijuana and other illegal drugs. But the likelihood of switching from marijuana to other illicit drugs varied from one country to another. For example, it was lower in the Netherlands than in Belgium, Spain and the United States. In addition, there were striking exceptions to the usual sequence. In Japan and Nigeria, for example, illicit drug users have rarely tried cannabis first.

"These findings suggest that the" gateway "model at least partially reflects unmeasured common causes rather than the causal effects of specific drugs on the subsequent use of other drugs," the authors concluded. "This implies that successful efforts to prevent the use of specific" gateway "drugs can not in themselves lead to a significant reduction in the use of subsequent medications."

The ban on marijuana may not be an effective way to reduce opioid use, even though cannabis use has a causal connection with the use of marijuana. other illicit drugs, depending on the mechanism involved. Cannabis use can lead to the consumption of other drugs, for example by putting people in touch with a black market where other intoxicants are also available. Violating the law on marijuana use, particularly if it is not detected by the authorities and imposes no penalty, could reduce psychological barriers to the use of other illicit drugs. People who discover from personal experience that government warnings about the dangers of marijuana use are exaggerated may be more skeptical of government warnings about other drugs.

Given that these three mechanisms are dependent on government policy on marijuana, one could expect that the relaxation of legal restrictions on marijuana would weaken the link between cannabis use and the use of other drugs. This is perhaps what happened in the Netherlands, which has tolerated, since the 1970s, the retail sale of marijuana by so-called coffeeshops, a policy justified in part by the belief according to which the separation of marijuana from other illegal drugs would make the progression less likely. A 2011 study found that "cocaine and amphetamine use is lower than the one predicted for the Netherlands", suggesting that "the separation of soft and hard drug markets can to be reduced the bridge ".

Does the legalization of marijuana increase opioid use?

If there is a causal link between cannabis use and the use of other drugs that is not simply an artifact of prohibition, the relaxation of legal restrictions on marijuana should lead to an increase in opioid consumption. Legalization can be expected to increase marijuana use by eliminating the risk of arrest, by reducing the stigma associated with drugs and by facilitating access (and ultimately, at lower costs). ). With cannabis use becoming more common, so should other drugs, including opioids. Yet, little evidence exists in states that have legalized marijuana for medical or recreational purposes. On the contrary, legalizing marijuana seems to reduce the use of opioids.

Studies have shown that marijuana laws for medical purposes are associated with reductions in high risk opioid userelated to opioids hospitalizations, during admissions for treatment of disorder of the use of opioidsas a percentage of fatally injured drivers positive test for opioids, and in the opioid prescriptions for Medicare and Medicaid the patients. In accordance with these results, other studies to have found that patients who use medical marijuana tend to reduce their use of prescription pain medications.

Between 1999 and 2010, a study According to results published in 2014, medical marijuana laws were associated with a 25% reduction in opioid-related deaths. A subsequent analysisIn contrast, the opioid-related death rate increased more rapidly in 20 jurisdictions that legalized medical or recreational use between 2010 and 2016 compared to other states. But as critics highlighted, the latter analysis wrongly classified several states as jurisdictions where marijuana was legally available, including Oklahoma, which has not legalized marijuana for medical purposes until 2018; Florida, Ohio and Pennsylvania, where medical marijuana programs only worked after 2016; and Georgia, where the use of medical extracts of cannabidiol (but not other cannabis-based products) was theoretically permitted only in the absence of legal supply.

A 2018 study found that the mere fact of having a marijuana law for medical purposes was associated with lower opioid-related death rates until 2010. After that, the laws themselves did not present no apparent benefit, but states with "legally protected and operational dispensaries" continued to see reductions, suggesting that "expanded access to marijuana for medical purposes facilitates the substitution of marijuana for potent opioids and addictive. A 2019 study also found that "states with active health clinics are seeing a decline in the rate of opioid deaths over time".

A 2017 study found that the legalization of marijuana for recreational purposes in Colorado was associated with a reduction in the number of opioid-related deaths. A study published the following year found a similar association in Washington.

These results are inconclusive, but they suggest that, until now, the legalization of marijuana has not contributed to the increase in the number of opioid-related deaths. There is also no clear link between increasing marijuana use and opioid use in national data. Enter 2002 and 2017According to the National Survey of Drug Use and Health, the proportion of Americans who reported using marijuana in the previous month has increased by more than 50%. The non-surgical use of prescription opioids has been more or less flat from 2002 to 2014, as well as the prevalence of substance use disorders. (The following figures are not comparable due to the changes to the questionnaire implemented in 2015.) The prevalence of heroin use in the last month doubled in 2014, but apartment from 2002 to 2013.

Persistent skepticism

"According to the teenage theory, the teenager begins to use illicit drugs with marihuana and then switches to heroin in search of thrills," said the National Commission on the marihuana and addictions, named by Nixon. it is noted in 1972. "According to the opposite view, the vast majority of marihuana users never become heroin addicts and deny the validity of a causal link." The commission was inclined to adopt this. last point of view, concluding that "the use of marihuana in itself does not dictate if other drugs will be used. "

Twenty-seven years later, a report On the medical potential of the organization's marijuana later became the National Academies of Science, Engineering and Medicine (NASEM) was also skeptical about the bridge theory. Although "most users of other illicit drugs first used marijuana," the authors said, "there is no evidence that marijuana can serve as a springboard on the basis of its particular physiological effect." On the contrary, "the legal status of marijuana actually makes it an introductory drug.

Harry Anslinger was clearly wrong when he claimed that marijuana, "if used for a long time", is inevitably[s] heroin addiction. Seven decades later, we recognize that marijuana users generally do not become heroin addicts. Among the Americans born in 1979, for example, the Survey data indicate that 96% of cannabis users do not switch to "hard" drugs.

It remains possible that the experience of marijuana use further encourages people to consume heroin or other opioids. But this theory is by no means necessary to explain patterns of drug use in the United States or in other countries. And even if there is some truth, the implications for marijuana policy are not obvious. If "the legal status of marijuana makes it an initiation drug", as NASEM had supposed in 1999, legalizing cannabis could reduce opioid use instead of increasing it. . Some evidence exists in states that have decided to allow the use for medical or recreational purposes.

Whether this is true or not, the moral argument against treating marijuana as a crime remains strong. Even though marijuana use makes opioid abuse more likely, it would only be one of the types of self-injury that prohibition aims to prevent. Like other forms of paternalism, the prohibition of marijuana interferes with the individual's sovereignty over his body and mind. This interference is particularly shocking, because those who would have benefited from it – those who would otherwise have used cannabis and eventually switched to opioids – are not the ones who bear the burden of law enforcement. The fear that some people who, by prohibition, deter cannabis use will otherwise become heroin addicts can not justify the use of force against a much larger group of people who do not violate the rules. rights of person.

[ad_2]

Source link