[ad_1]

This illustration of Jupiter’s moon, Europe, shows how the icy surface can shine on its night side, the side opposite the Sun. Variations in the glow and color of the glow itself could reveal information about the composition of ice on the surface of Europe. Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech

New laboratory experiments recreate Europa’s environment and find that the icy moon shines, even at night. The effect is more than just a cool visual.

As Europa’s frozen ocean moon orbits Jupiter, it withstands the incessant pounding of radiation. Jupiter zaps Europa’s surface night and day with electrons and other particles, bathing it in high-energy radiation. But as these particles pound the moon’s surface, they can also do something otherworldly – make Europa glow in the dark.

New research from scientists at NASASouthern California’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory details for the first time what the glow would look like and what it might reveal about the makeup of ice on the surface of Europe. Different salty compounds react to radiation differently and emit their own unique glow. To the naked eye, this glow would sometimes be slightly green, sometimes slightly blue or white and with varying degrees of brightness, depending on the material.

Scientists use a spectrometer to separate light into wavelengths and relate different “signatures”, or spectra, to different compositions of ice. Most observations with a spectrometer on a moon like Europa are taken using sunlight reflected off the side of the moon, but these new results illustrate what Europa would look like in the dark.

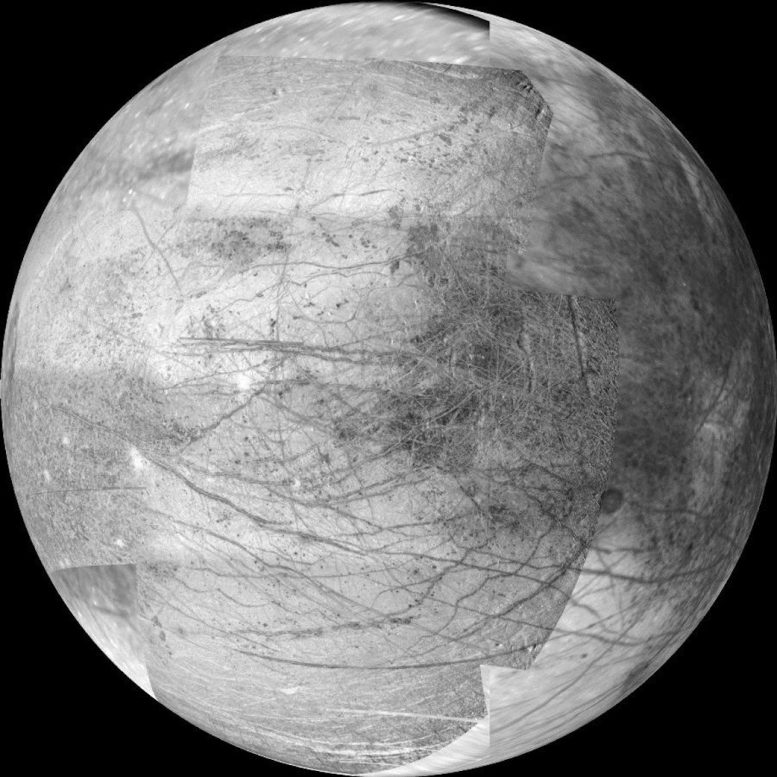

The puzzling and fascinating surface of Jupiter’s icy moon, Europa, looms large in this newly reprocessed color view, taken from images taken by NASA’s Galileo spacecraft in the late 1990s. This is the color view of Europa from Galileo which shows most of the moon’s surface at the highest resolution. Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / SETI Institute

“We were able to predict that this nocturnal ice glow could provide additional information on the surface composition of Europa. The way this composition varies could give us clues as to whether the conditions in Europa’s ports are suitable for life, ”said JPLby Murthy Gudipati, main author of the book published on November 9 in Nature Astronomy.

This is because Europa has a vast global interior ocean that could percolate to the surface through the moon’s thick crust of ice. By analyzing the surface, scientists can learn more about what lies below.

Shine a light

Scientists deduced from previous observations that Europa’s surface could be made up of a mixture of ice and salts commonly known on Earth, such as magnesium sulfate (Epsom salt) and sodium chloride (salt of table). New research shows that incorporating these salts into water ice under Europa-like conditions and projecting them with radiation produces a glow.

It wasn’t a surprise. It is easy to imagine a glowing irradiated surface. Scientists know that shine is caused by energetic electrons penetrating the surface, energizing molecules below. When these molecules relax, they release energy in the form of visible light.

This mosaic of 12 images offers the highest resolution view ever of the moon side of Jupiter Europa facing the giant planet. It was obtained by the camera aboard NASA’s Galileo spacecraft on November 25, 1999, during Jupiter’s 25th orbit. Credit: NASA / JPL / University of Arizona

“But we never imagined we would see what we ended up seeing,” said Bryana Henderson of JPL, co-author of the research. “When we tried new ice compositions, the glow was different. And we all looked at it for a while and then we said, ‘This is new, right? Is it really a different glow? So we pointed a spectrometer at it, and each type of ice had a different spectrum.

To study a laboratory mockup of Europa’s surface, the JPL team built a unique instrument called the Ice Chamber for Europa’s High-Energy Electron and Radiation Environment (ICE-HEART) testing. They took ICE-HEART to a high-energy electron beam facility in Gaithersburg, Maryland, and began the experiments with an entirely different study in mind: to see how organic matter under Europe’s ice would react to radiation explosions.

They didn’t expect to see variations in the glow itself related to different compositions of ice. It was – as the authors called it – a fluke.

“Seeing sodium chloride brine with a significantly lower glow level was the ‘aha’ moment that changed the course of research,” said Fred Bateman, co-author of the article. He helped conduct the experiment and provided radiation beams to the ice samples at the Medical Industrial Radiation Facility at the Maryland National Institute of Standards and Technology.

A moon visible in a dark sky may not look unusual; we see our own moon because it reflects sunlight. But the European glow is caused by an entirely different mechanism, the scientists said. Imagine a moon that is constantly shining, even on the night side – the side opposite the sun.

“If Europa weren’t under that radiation, it would look like our moon – dark on the shaded side,” Gudipati said. “But because it’s bombarded by radiation from Jupiter, it glows in the dark.”

Scheduled for launch in the mid-2020s, NASA’s next flagship mission, Europa Clipper, will observe the surface of the moon in multiple flyovers while orbiting Jupiter. Mission scientists are reviewing the authors’ results to assess whether a glow would be detectable by the spacecraft’s scientific instruments. It is possible that the information gathered by the spacecraft could be combined with measurements from the new research to identify salty components on the moon’s surface or clarify what they might be.

“It’s not often that you’re in a lab and say, ‘We might find this when we get there,’” Gudipati said. “Usually it’s the other way around: you go there and find something and try to explain it in the lab. But our prediction comes down to a simple observation, and that’s what it is. “

Missions like Europa Clipper contribute to the field of astrobiology, interdisciplinary research into the variables and conditions of distant worlds that might harbor life as we know it. While Europa Clipper is not a life-detecting mission, she will perform a detailed reconnaissance of Europa and examine whether the frozen moon, with its underground ocean, has the capacity to support life. Understanding the habitability of Europa will help scientists better understand how life developed on Earth and the potential to find life beyond our planet.

[ad_2]

Source link