[ad_1]

MELISSA BENSOUDA, from Kansas City, Missouri, was 25 years old when diagnosed with advanced kidney disease. She had to start dialysis by connecting three times a week to a machine that was filtering her blood. "It's erased," she says. Sick and tired, Ms. Bensouda struggled to look after her children and continue working full time. To get a place on the waiting list for a kidney transplant, she had to first tackle other health problems. It took a year and $ 10,000 to treat dental problems that people with kidney disease are prone to. In 2012, after nearly ten years of dialysis, Ms. Bensouda was transplanted. The new kidney only lasted five years. She is back on the waiting list, with 95,000 other Americans.

In a typical year, only one in five is grafted. One in ten would die or become too sick and abandon the list. Europe is struggling too. In the European Union in 2013, more than 4,000 patients died on a waiting list for kidneys.

And waiting lists are often just the tip of the iceberg. For example, many patients in Europe suspect that doctors prefer to keep them on dialysis – an important and lucrative business – rather than preparing them for a transplant. In America, many people who need a transplant never join the list because they can not afford the drugs they need afterwards.

Some people's kidneys fail because of a genetic disease or injury. But the main reason is diabetes. This is mainly due to obesity, which is rampant in more and more countries. Thus, the waiting lists for the kidneys will become even longer.

Shortening them will save more than personal misery. In Britain, a kidney transplant, with an average duration of 10 to 13 years, begins to save the National Health Service (NHS) the money compared to the cost of dialysis the third year. In America, a transplant saves $ 60,000 per year compared to a remaining dialysis. (In poor countries, few people can afford dialysis and therefore can not wait for a deceased donor, which means no waiting list.)

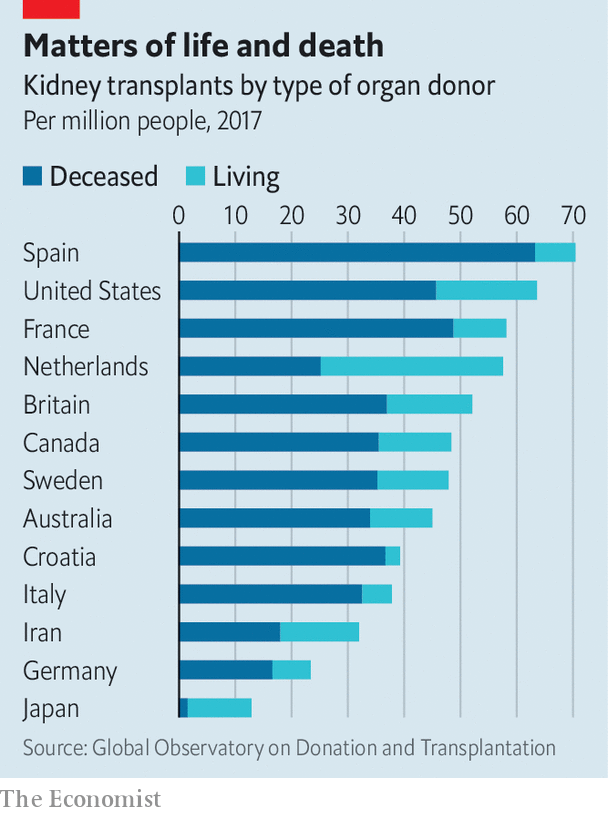

About two-thirds of kidney transplants in rich countries come from deceased donors (see chart). The rest comes from living donors who separate themselves from a kidney to help someone else. A kidney can perfectly handle the work of the two with which most people are born.

Historically, Northern European countries have promoted kidney donations from living donors. Southern Europeans have reservations about the need for unnecessary surgery. Instead, they looked for ways to increase the gifts of the dead. In Spain, only 15% of families refuse to donate organs of deceased parents; in Britain, a third says no. Some do not know what the deceased wanted; others think that doctors might not do everything in their power to save their loved ones if they can harvest the organs. Cultural differences also play a role. Most Japanese, for example, are uncomfortable with taking organs from a dead body.

In general, more people say they want to donate than volunteering to add their name to a donor registry. This has prompted more countries to follow Spain, which has the highest organ donor rate in the world. In 1979, it became the first country to adopt a law instituting organ donation upon death, an alleged choice of whoever did not register. England, France and the Netherlands have recently amended their laws to this effect; Australia and several other countries are debating this idea.

But in practice, these new laws may not make much difference. In Spain, for a decade after 1979, donations have not increased. They did so only after other measures were introduced: a new transplant coordination center; intensive care physicians and nurses trained in organ donation; and looking for potential donors has become the norm. Croatia has copied the Spanish model (renaming it "Croatian model") and has seen organ transplants more than double between 2007 and 2011.

With the exception of a few presumed consent countries, parents still do not have the last word, as an additional guarantee (and to avoid the outcry from detractors of donation of organs) . Mark Murphy, outgoing president of the European Federation of Kidney Patients, sees the chaos around the alleged consent as a distraction. Politicians, he says, prefer to blame the organ shortage for bereaved people rather than investing in the logistics and incentives that have been proven to increase the number of transplants.

Conservation orders

Beatriz Domínguez-Gil, of the Spanish National Transplant Organization, explains that Spain has adapted earlier than other countries to aging the deceased donor pool. His doctors learned to transplant organs from donors aged 70 to 80 (usually elderly recipients). One-quarter of deceased donors are people with devastating brain damage who are undergoing organ preservation as part of their end-of-life care. In many countries, they are sent to palliative care and lost as donors.

At what stage are doctors allowed to recover extremely important organs? In less than half of European countries, the process can start after stopping the heart (and organic lesions), rather than when the brain also stops. Across Europe, the "no contact" time before organ harvesting can begin varies between 5 and 20 minutes.

Nowhere, however, enough kidneys are available from the dead. Only 1 to 2% of people die in a way that makes their organs fit for donation, for example as a result of a brain injury suffered during an accident. So, life is necessary. Some countries, such as Ireland and Germany, require that a living donor has close links with the patient. But many allow people to give a kidney to whoever they want. A 49-year-old American, Paula King decided to donate a kidney to a stranger after finding out the difficulties faced by a family member in finding a bone marrow donor, while no member of the family was tied. "I wanted to ease the stress of another family at the mercy of a stranger," Ms. King said. In Britain, these so-called "undirected" donors account for almost 10% of living donor transplants.

In the past, older people were rarely considered potential donors. But it's clear that this is wrong, says Dorry Segev of Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore. In fact, he says, it's hard to predict the risk of kidney failure for life for a 25-year-old, while a man who has done well for 70 years will likely draw out better with one kidney. Between 2014 and 2018 in America, the number of living kidney donors aged 65 and over doubled; those aged 50 to 64 increased by more than a quarter.

A kidney donor usually needs two days at the hospital and about a month to recover. About 20% suffer from complications, usually minor ones. In many countries, some potential donors are dissuaded by travel and other costs. In the Netherlands, where the living organ donor rate is the highest in the world of rich countries, kidney donors are entitled to three months' paid leave, as well as the payment of related expenses, even those requiring the guard of a dog. In America, on the other hand, donors pay only certain expenses, and only if they are poor.

Nearly half of potential kidney donors are not biological matches for the person they want to help. The renal exchange systems have evolved. In these cases, a patient receives a kidney from an appropriate living donor only if someone does one on his behalf for another patient. Launched by South Korea in 1991, national kidney kidney programs have been adopted by Australia, Canada and many European countries. In America, some transplant centers and several non-profit groups manage their own.

The UK trading system performs an algorithmic correspondence search every quarter. Undirected donors are valuable because they can be used where they are most needed, depending on blood group composition and other criteria, and thus initiate a chain of other matches, significantly increases the number of transplants. Donors who participate in a kidney-to-kidney exchange have scheduled surgeries as close as possible – not because some can turn around (which is rare), but because "life comes to humans," says Lisa Burnapp from NHS. In a long time, a recipient may become too sick for the operation, for example, or something unexpected may happen to prevent a donor from advancing.

Such systems are particularly beneficial for people who have received a blood transfusion or are waiting for a second transplant because donors who are suitable for their antibody mix can be extremely rare. If all living donors in America were allocated as part of a national exchange, the kidney transplants of these volunteers could double, says Jayme Locke from the University of Alabama in Birmingham.

Buddy, can you spare a kidney?

But many people, of course, can not bring themselves to ask a kidney to other people. The task is not just embarrassing, says Price Johnson, who speaks from experience; The goal is to find several volunteers in the hope that at least one of them will stick to these numerous tests and get a medical certificate for the operation.

To help with this, patient groups have developed a model of training a friend, finding people willing to research on behalf of the patient and teaching them what to do. A dedicated Facebook app creates a social media appeal with links to validated kidney donation information. A small trial conducted in the United States revealed that after ten months, app users were six times more likely than non-users to find a donor. But this "lost" approach to finding donors means the loss of privacy, Johnson said. He wants donors to be paid.

The only country where this is legal is Iran. Buyers and sellers are mediated by patient foundations. The price of a kidney roughly corresponds to the average annual income of a family living on the poverty line. The vast majority of sellers are poor; some sell a kidney to pay off their debts in order to avoid jail time. Poor buyers depend on the help of charitable organizations.

American academics have proposed versions of this system as a solution to the lack of kidneys in the country. The patient groups did not weigh all their weight in this idea. They are pushing for European-style benefits for living donors.

In five to ten years, advances in medical technology could make this debate useless. Xenografts (human-adapted pork kidneys) and artificial kidneys derived from bioengineering could become viable options within a decade. But for thousands of people whose kidneys have already stopped working, these medical miracles will come too late. They need a better system to organize the proven wonder of human-to-human transplants.

[ad_2]

Source link