[ad_1]

Two articles have dealt a further blow to the idea that Venus’ atmosphere may contain phosphine gas – a potential sign of life.

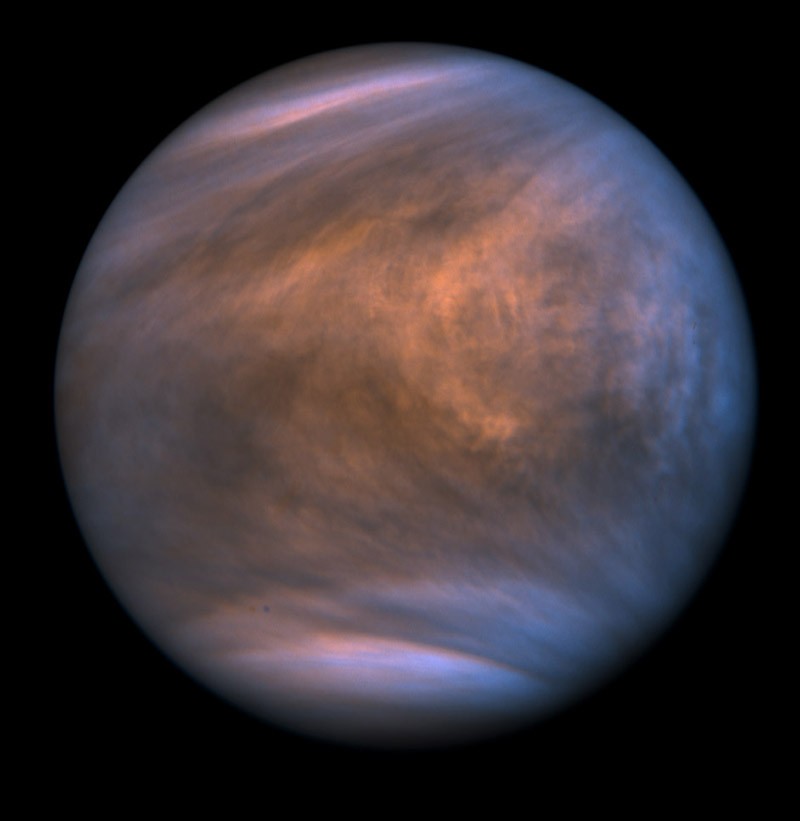

The claim that there is phosphine on Venus rocked planetary science last September, when researchers reported spotting the gas’s spectral signature in telescope data.1. If confirmed, the discovery could mean that organisms drifting among the Venusian clouds release the gas. Since then, several studies have disputed – although not fully debunked – the report.

Now, a team of scientists has released the biggest review to date. “What we’re bringing to the table is a comprehensive look, another way to explain this data that isn’t phosphine,” says Victoria Meadows, an astrobiologist at the University of Washington in Seattle who has helped lead the latest studies. Both papers were accepted for publication in Letters from the Astrophysical Journal and were posted to the arXiv preprint server on January 26.

Alternative explanations

In one study, Meadows and his colleagues analyzed data from one of the telescopes used to make the phosphine statement – and were unable to detect the spectral signature of the gas.2. In the other, the scientists calculated the behavior of gases in Venus’ atmosphere – and concluded that what the original team thought was phosphine is in fact sulfur dioxide (SO2), a common gas on Venus and which is not a possible sign of life3.

The latest articles show quite clearly that there is no sign of gas, says Ignas Snellen, an astronomer at Leiden University in the Netherlands who has published a different review of the phosphine claim.4. “This makes the whole debate over phosphine, and possibly life in the atmosphere of Venus, completely irrelevant.”

Jane Greaves, an astronomer at Cardiff University in the UK who led the team that made the original phosphine claim, says she and her colleagues are still reading the new articles and will comment after reviewing them .

The stakes to confirm the presence of phosphine on Venus are enormous. On Earth, gas – which is made up of one atom of phosphorus plus three atoms of hydrogen – can come from industrial sources such as fumigants, or from biological sources such as microbes. During the first report of the discovery of phosphine on Venus, Greaves and his colleagues said that its existence could mean that there is life on the planet, as the other origins of the gas were not obvious.

But the claim rests on a chain of observations and deductions that other scientists have collapsed in recent months.

Chipping away

Greaves ‘team first used the James Clerk Maxwell Telescope (JCMT) in Hawaii to observe a spectral line in Venus’ atmosphere at a frequency of 266.94 gigahertz – just around the frequency where the phosphine and the SO2 absorb light. Scientists confirmed the existence of the line using the Atacama Large Millimeter / Submillimeter Grating (ALMA) in Chile. With ALMA, they looked for other spectral lines that they would expect to see if the line came from SW2, and did not find them. This, they said, suggested that the line they observed at 266.94 gigahertz was from phosphine.

But it turned out that the ALMA data used by the team had not been processed correctly by the observatory. After the phosphine debate started on Venus, ALMA officials realized the mistake, extracted the raw data, reprocessed it, and released the reworked batch in November. Greaves and his colleagues analyzed the reprocessed data and concluded that they were still seeing phosphine – albeit at a much lower level than they initially reported.5.

This restated ALMA data is at the heart of one of the new studies contesting the claim. A team comprising Meadows and led by Alex Akins, a research technologist at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif., Aimed to replicate the work of the Greaves group by analyzing the reprocessed data that had been made public. But the researchers did not observe the spectral line of phosphine. “We just couldn’t see it,” Akins says.

This is the first analysis of restated ALMA data to be published by an independent team.

The second study explores the 266.94 gigahertz function, seen by the JCMT. Andrew Lincowski, an astronomer at the University of Washington, led Meadows, Akins and others in modeling the structure of the atmosphere of Venus at different altitudes. They found that the JCMT sighting was best explained by the presence of SO2 more than 80 kilometers above the surface of the planet – not by phosphine 50–60 kilometers above the surface, as stated by Greaves’ team.

However, the case is not yet closed. The new studies argue against the presence of phosphine, but cannot exclude it entirely. “There’s enough leeway there,” Meadows says.

Ultimately, the debate can only be resolved with new sightings of Venus, many of which are expected in the months and years to come, Akins says. “Until we see something new, it’s probably going to keep coming and going.

[ad_2]

Source link