[ad_1]

Many Californians have spent New Years Eve in a safe place with their immediate families. Dr Nick Kwan, assistant medical director of emergency services at Alhambra County Hospital in Los Angeles, spent it with a COVID-19 patient who entered code blue – cardiac or respiratory arrest – five different times.

Code blue forces medical staff to call for a quick and intense response to resuscitate the patient.

“It’s exhausting mentally, physically and emotionally,” said Kwan, who struggled to articulate the toll that a one-month increase in COVID-19 patients represents for him and other Los County hospitals. Angeles.

“It’s a full Category 10 … It’s literally World War III,” he said.

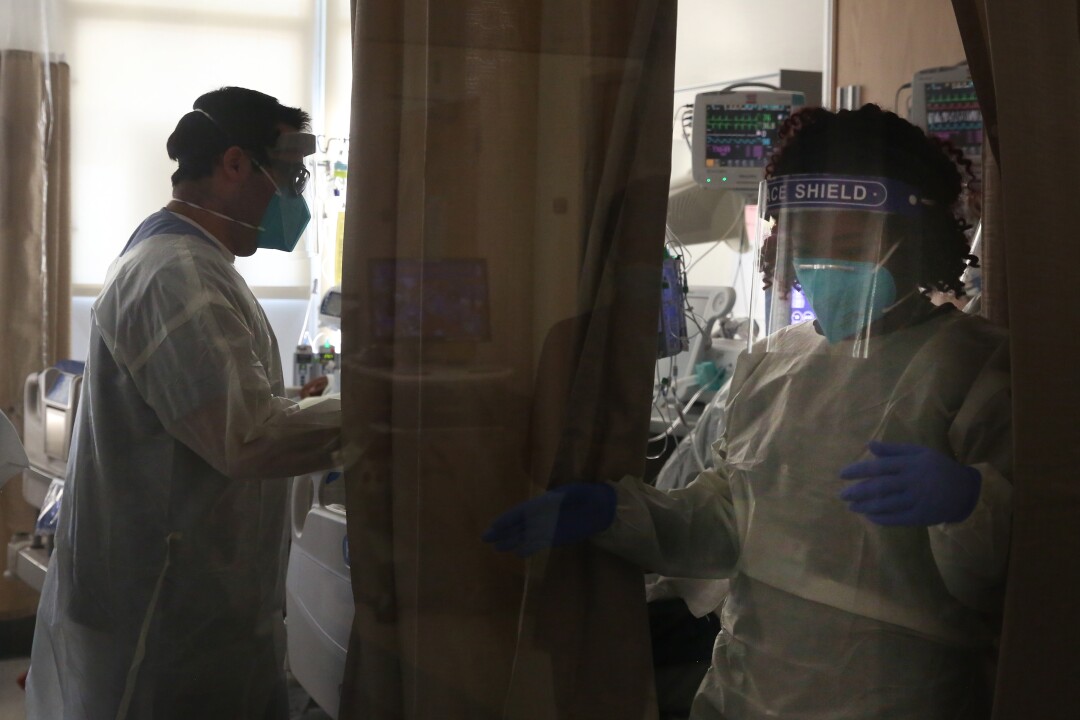

Doctors and hospital nurses are treating COVID-19 patients in a makeshift ICU wing this week at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center in West Carson. The hospital does not have open beds for incoming patients and has worked tirelessly to create additional beds for the influx of coronavirus patients.

(Dania Maxwell / Los Angeles Times)

“It’s not the volume of patients,” he says. “It’s the intensity and the illness of the patients. I never thought some of these numbers were consistent with life, with patients getting sicker than you might imagine.

In LA County and much of Southern California, hospitals are grappling with an influx of critically ill COVID-19 patients and a lack of resources, including personnel and vital infrastructure, such as oxygen piping.

On Friday, the state called the US Army Corps to help six hospitals facing serious problems with the supply of oxygen to patients who needed it.

The Alhambra hospital was not one of those, but it was nonetheless stretched by COVID-19 and the emotional toll it has caused to everyone involved.

“I don’t think a lot of people on the outside see what we’re seeing,” Kwan said. “It’s hard until you’re there, until your family and loved ones are there.”

Since Thanksgiving, the 144-bed hospital that serves as the melting pot of the San Gabriel Valley, many of whose residents are first and second-generation Latino and Asian immigrants, has seen a steady wave of patients with breathing difficulties.

Kwan said that in addition to the Alhambra, he knew several other hospitals along the corridor of Highway 210 are full and tired under the burden of the current push.

The waiting room of the Alhambra hospital is now a COVID service. Regular beds were quickly converted to USI beds. And the ambulances are waiting outside with the patients arriving because “physically we can’t accommodate the patient” at that time, Kwan said. “It’s at all levels. The virus doesn’t care who you are. You can be sick, healthy, young, old. ”

Younger patients have died and a patient in her 90s was discharged from the hospital with an oxygen tank.

“It’s so unpredictable in each case,” he added.

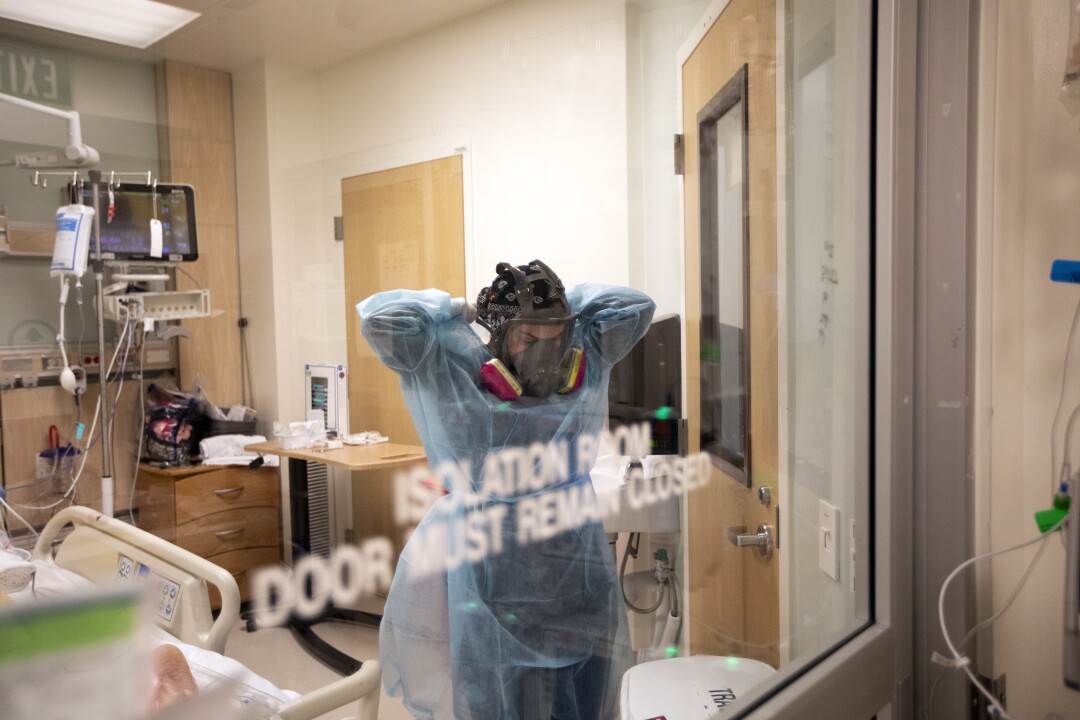

Registered Nurse Armela Masihi takes off her isolation gown as she exits a COVID-19 patient’s room at the ICU at Martin Luther King Jr.

(Francine Orr / Los Angeles Times)

“On November 29 and 30, we started to see the surge, and it hasn’t stopped since then,” Kwan said. “It’s easy to tell these are holiday gatherings – or maybe the colder weather. … Christmas and New Years scare me, and I think the worst is yet to come.

A state-sponsored nurse arrived recently to help combat the patient load, and it was a necessary morale booster, Kwan said. Still, staff fear the December deluge may be the harbinger of a long, deadly winter.

“For next month, I don’t see the end. It will continue to accumulate and we must be prepared.

It was a similar picture in Santa Clara County, where hospitals remained stretched to the limit, with 50 to 60 patients stuck in emergency rooms every day waiting for a hospital bed.

According to Dr. Marco Randazzo, emergency doctor at O’Connor Hospital in San Jose and St. Louis Regional Hospital in Gilroy.

“This has been the state of the pandemic for several weeks and it shows no signs of slowing down,” said Dr Ahmad Kamal, director of health preparedness for Santa Clara County. The daily rate of coronavirus cases there is more than 10 times higher than it was on October 30. “What we are seeing now is not normal.”

At the Alhambra hospital, the virus hit staff directly: a hospital emergency doctor died of COVID-19 and a nurse who contracted the virus was absent for months, Kwan said.

“Everyone is exhausted. Our CEO is exhausted. All of our medical staff are exhausted, ”Kwan said.

Kwan and other staff have had to get used to being the last person a patient sees before they die, with families being kept away from loved ones.

Chaplain Anne Dauchy, left, places her hand on Dr Marwa Kilani to comfort her. Kilani cries after speaking to the family of a patient as he stood inside the intensive care unit Thursday at Providence Holy Cross Medical Center in Mission Hills, Calif. Three people have died of complications from COVID in the morning along this corridor.

(Francine Orr / Los Angeles Times)

“You cry with the families of the patients. It’s just sad, ”he says. “I have the impression that this virus is attacking all of our humanity.”

Behind the fatigue and strain on resources is the simple fact that COVID-19 patients stay in hospital longer than the average patient and require more resources.

There are constant concerns about whether there will be enough ventilators, and oxygen tanks are sometimes depleted. But a major concern is simply space: “It doesn’t matter if it’s the Cedars, USC or the Alhambra – the hospital is only that big.”

Mortuary space, he said, is also limited – and an ongoing concern.

“When was the last time I thought we were going to run out of morgue space?” I never thought that would be one of my concerns.

Many patients who come for routine ailments – such as family members who brought their babies to the emergency room on New Year’s Eve – are treated in the parking lot, sometimes even in their vehicles.

Kwan said he knows the consequences of the pandemic: shutting down businesses, family and friends limiting social gatherings. He has not seen his mother since February and his father since March. Her children waited until five days after Christmas to open the presents and celebrate with their father.

“I would tell people it’s serious. Help us fight this war, ”he said. “It’s a group effort – we can’t figure this out on our own. It’s really about raising public awareness and a collective effort to conquer that.

Kamal, the Santa Clara County doctor, pleaded with the public not to give up wearing masks, staying socially distant and canceling rallies. There are indications in the Bay Area and elsewhere these measures have helped to stem the spread.

“We know,” he said, “that our decisions and actions are driving the curve of this pandemic.”

Chaplain Kevin Deegan, right, kneels as nurse Cristina Marco leans in to listen to Domingo Benitez, 70, inside the COVID unit at Providence Holy Cross Medical Center.

(Francine Orr / Los Angeles Times)

[ad_2]

Source link