[ad_1]

IT CAN START with something as trivial as a little cough that will not go away. But often, lung cancer causes no symptoms until it is too late. Ask Graham Thomas, who in 2014 discovered that hiding behind his pneumonia was Stage IV lung cancer. Stage IV is the medical jargon of a tumor that has spread to other parts of the body. There is no stage V.

Thomas is now speaking in a campaign led by the Roy Castle Lung Cancer Foundation, a charitable organization, to raise public awareness about the disease in Britain. He started smoking at age 14 and says that people think that he himself carries the disease and that it is the cancer that deserves the least sympathy. But he argues that this should perhaps not be the case because it is the cancer that kills the most.

One of the reasons lung cancer is so deadly is that at the time of diagnosis, three-quarters of people have already arrived, like Mr. Thomas, at stage IV. In Europe, the five-year survival rate after diagnosis is about 13%, with little variation across countries. Finding the tumors earlier would allow them to be treated before they spread, which would improve outcomes and reduce medical costs. Yet, many places that willingly invite people to participate in screening programs to detect breast, bowel, prostate and cervical cancers have withstood the idea to extend the idea to lung cancers.

Screening Screening

The question is whether such screening would do more good than harm. The history of screening shows that the answer is not obvious. In 1985, for example, Japan launched a mass screening program for neuroblastoma, a rare tumor of the infantile nervous system. The program unmasked 337 tumors of this type in the first three years, but two decades later, there was no evidence that it had reduced the number of dying children. The effort was mainly used to detect slow-growing tumors that probably would not have had any adverse consequences. Yet the discovery of these tumors had prompted many unnecessary treatments.

Prostate cancer screening is also proven. The current test often raises concerns about a possible cancer that turns out not to be there (false positive). However, to achieve this, one must perform tests such as invasive biopsies, painful and likely to cause infection. If a group of men aged 55 to 69 is screened regularly for more than a decade, 12% of them will have such a false positive and may therefore undergo an unnecessary biopsy. Conversely, screening for prostate cancer misses 15% of men who actually have cancer (a false negative).

Moreover, even when prostate screening is correct, by identifying a tumor that is actually present, this tumor would often not have shortened the life of the patient, because he would have died of other causes before his death (overdiagnosis). . Yet, all men screened for cancer are offered treatment, and many take it, risking side effects such as incontinence and impotence. According to Bob Steele, professor at the University of Dundee and chairman of the board United Kingdom National Control Committee: "You must treat 30 men to prevent one from dying."

The first evidence that lung cancer screening could be beneficial, despite this type of concern, comes from an American study called National Lung Screening Trial.NLST), which took place between 2002 and 2009. The NLST recruited around 53,000 people aged 55 to 74 who had already smoked at least 30 pack years (one year-pack equals one pack of cigarettes per day per year). He tested standard chest X-rays against low-dose computed tomography (CT) -An upgrade Xtechnique based on the rays. The participants were screened once a year for three years and appropriate treatment was offered to those whose examinations suggested the presence of tumors. At the end of the trial, those who had been CTscanned were 20% less likely than those who had been X– having died of lung cancer. This equates to three fewer deaths per 1,000 people screened and also results in a 7% decrease in all-cause mortality.

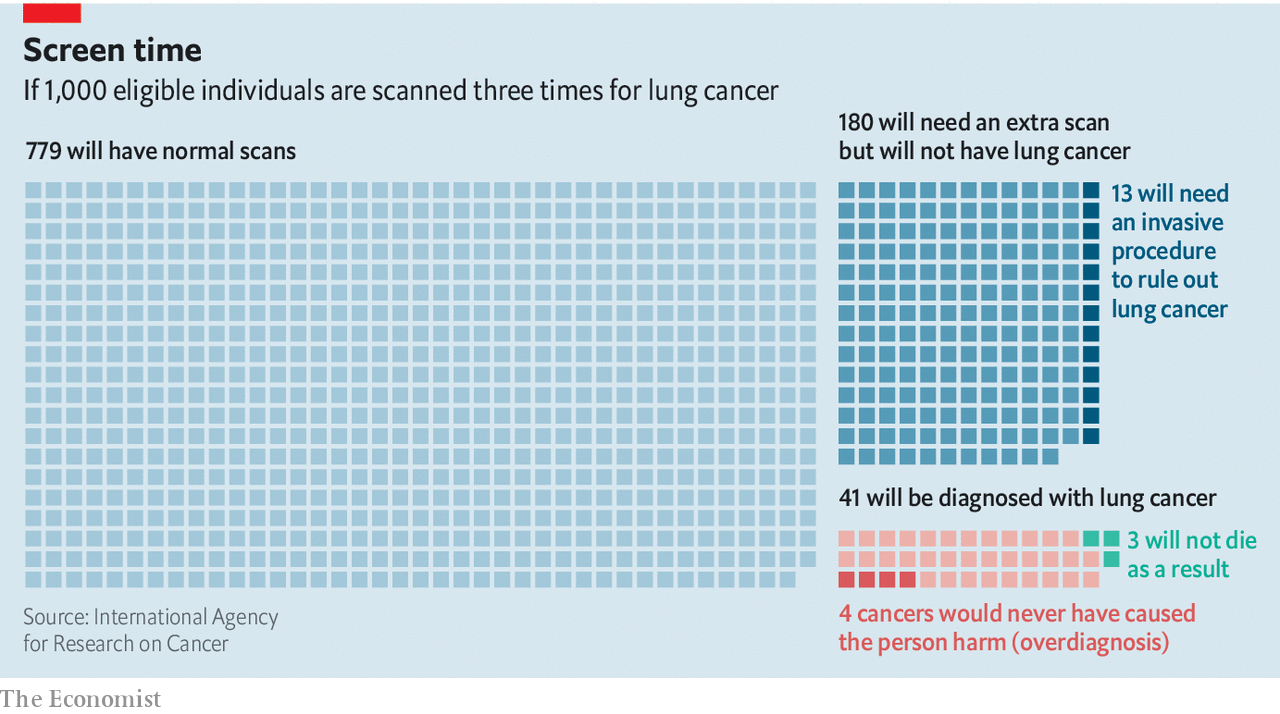

the NLST established CT sweep as a route to take. As noted by Hilary Robbins of the International Agency for Research on Cancer, part of the World Health Organization, this trial still raised concerns about false positive results, as 356 out of 1,000 people needed Follow up. However, improvements in the protocol used, which now ignores the smallest abnormalities because they are rarely cancerous, have halved false positive rates (see chart) and the number of people with complications also decreased.

The last try, NELSON, was carried out in Europe. It took ten years and included four annual analyzes. Although it has not yet been officially released, its main findings were announced last year and were extremely encouraging.

Two-thirds of the cancers discovered in the experimental group of the trial were in Stage I or II of their growth and could therefore be treated prominently. In the control group of the trial, however, two-thirds were in stage III or IV. In addition, NELSON had a more nuanced approach to the problem of false positives. If anything potentially sinister was seen, the protocol used was to order a three-month follow-up analysis. It is only if growth has developed in the meantime that it is considered likely to be cancerous and treated accordingly. Screening, researchers behind NELSON showed a decrease in mortality of 26% in men and 61% in women during the study.

Such evidence has convinced some (but not all) that lung cancer screening is useful in certain circumstances. And in one part of the world, this belief is translated into action. It is currently expected that more than half a million people in England, smokers or former smokers, will be offered, over the next four years, the opportunity to undergo a lung health examination at a local clinic. This follows a pilot project in Manchester that examined 2,541 people and found 61 patients with lung cancer – among which 80% of the cancers were at an early stage.

There is of course the question of cost, which some say is too high. Economists measure the effectiveness of medical technology based on the amount of health gained for the money spent. The health gain unit used is the QALY (Quality-adjusted life year, which attempts to take into account the patient's experience and increased life expectancy). As a result, the Manchester study was extremely effective. It cost £ 10,069 (approximately $ 13,000) per QALY-One third of the sum fixed by the NHS as the maximum for a procedure to be considered profitable.

Although some skeptics still claim that screening expenditures would be better used to try to prevent people from smoking – or, better still, to prevent them from getting started – the case of smokers' lung cancer screening now appears good. There is a ride, though. Focusing screening on smokers will certainly give the best results. But this will leave out of five patients with the disease who has never touched a cigarette in their life. To be cost-effective, screening must focus on those who, like Mr. Thomas, knowingly put themselves at risk. All others will be excluded from the process. What irony!

[ad_2]

Source link