[ad_1]

It’s a Inside science story.

It was late 1791 or early 1792, in a palace on the right bank of the Seine in Paris. The world was about to change – drastically. France was on the brink of revolution as different factions fought for control. The country’s queen, Marie-Antoinette, has been closely watched and watched after an unsuccessful escape attempt to Varennes, France. But she still managed to send letters to her friend and alleged lover, Swedish Count Axel von Fersen.

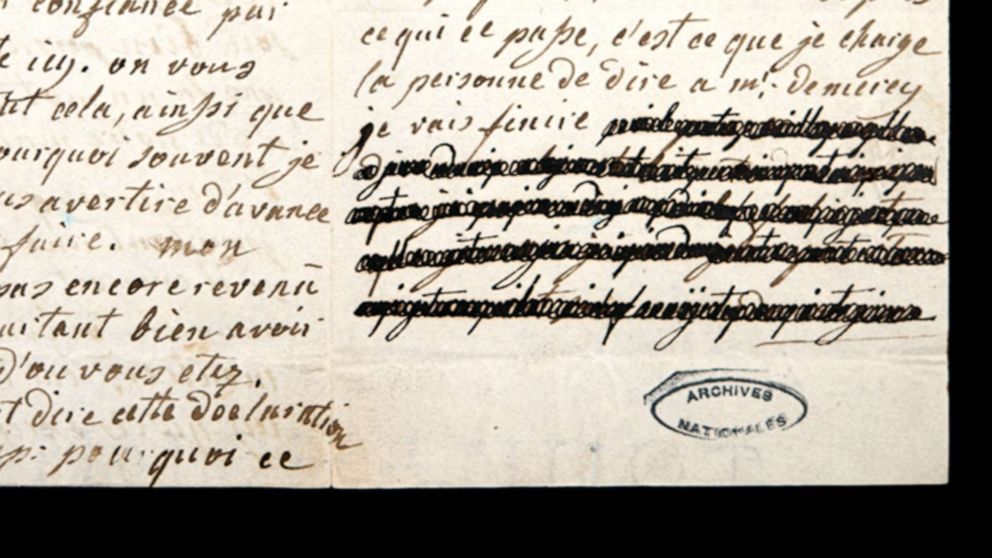

For 150 years, researchers have wondered what secrets these letters hold. Von Fersen had made copies, but the words and passages inside the copies were heavily redacted by an unidentified censor who had blackened them in ink.

Now the world has a glimpse into the romantic life of Antoinette and von Fersen. In a paper recently published in the journal Science Advances, researchers revealed the once-hidden words and phrases from the letters. Scientists used a technique called X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy, which can detect chemical signatures of different inks without damaging documents. The letters show a deep friendship between Antoinette and von Fersen, but do not confirm that they were lovingly entangled.

“It’s always very interesting to see what is included in these thoughts that a person considers to be really intimate and decides to hide,” said Anne Michelin, conservation researcher at the National Museum of Natural History in Paris, co-author of the new research. “We know what is really intimate and what is public information.”

Michelin and his colleagues applied X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy to analyze the written sections of 15 letters. The researchers successfully read eight of the letters, where they found consistent differences in the copper / iron and zinc / iron ratios of the inks in the original texts and the ink in the essays, which they mapped to reveal the original text. The researchers also used statistical analyzes to clarify more sections.

The censored handwriting showed emotional testimonies of affection between the Queen of France and the Swedish count: words like “beloved”, “a tender friend”, “adore” and “madly”.

Scientists add that many letters in the archives allegedly written by Marie-Antoinette were actually copies of the originals made by von Fersen. Copying letters was common practice at the time, for administrative reasons (like backup storage before hard drives). Because the ratio of the ink elements in the handwriting and the blacked out sections was similar, von Fersen was likely the person who censored the documents.

The count wrote a line and added text above with the same ink to ensure the line would still be readable, replacing “the letter of 28 made me happy” with the softer “letter of 28 m ‘has arrived “. The researchers say this was done for political reasons, to avoid a compromising situation if the letters fell into the wrong hands.

Looking beneath the surface to reveal something hidden is a common goal in documentary research, said Aniko Bezur, a researcher at the Institute for the Preservation of Cultural Heritage at Yale University, who was not involved in the Antoinette research. Bezur was part of a team that recently determined that the Vinland Map, a document that appeared to reflect Viking voyages to North America, was a fake.

She said the information superimposed on other writings poses challenges and opportunities for researchers. “Sometimes you are really lucky because the ink is different enough that you can tell, and sometimes you are unlucky.” Bezur said the article’s authors aren’t just using a tool to discover handwriting – they’re discussing many approaches that would be helpful to other researchers.

The researchers are focusing on non-invasive methods so that the documents can be preserved for future scientists, who may have even better techniques to use. “There is a cost to everything we do in terms of handling objects,” Bezur explained. “We need to do this kind of cost-benefit analysis that involves the custodians and owners of this object so as not to jeopardize future attempts at decoding if there are new techniques or new analytical approaches that can still do a job. best that we can. “

If Marie-Antoinette was writing today and wanted her posts to be kept secret, she might delete her texts or make changes to changes tracked in a document, Bezur said. These types of changes would be discovered by computer scientists who would decode a different method of changing the correspondence. “It’s an interesting contrast between today and centuries ago… how different our communication practice has become.”

Michelin was struck by the interplay of intimate communication and political issues in the letters, which also include commentary on current events and politics. “The words are really strong, so you can see a really sincere relationship. But it’s also influenced by this time of crisis: it’s interesting to see how political events and personal relationships come together.”

Inside science is a nonprofit print, electronic and video journalism information service owned and operated by the American Institute of Physics.

[ad_2]

Source link