[ad_1]

This is one of the most exciting things in all of astronomy: the discovery of a new planet.

But the push to recognize a particular object – an apparent orb several times the size of Earth that appears to rotate along the outer solar system – as a major planet has been complicated by the story of an Earthman.

The scientist who championed the name of a New ninth planet, Caltech astronomer Mike Brown, is the same who got the old ninth planet, Pluto, removed from list teachers teach and students memorize.

Many of Brown’s fellow astronomers are less than happy.

To be clear, most scientists The Daily Beast spoke to said they love Brown, respect his work, and support his efforts to add at least one new planet to the current roster. They just don’t agree with what he did to Pluto in 2006. Strongly.

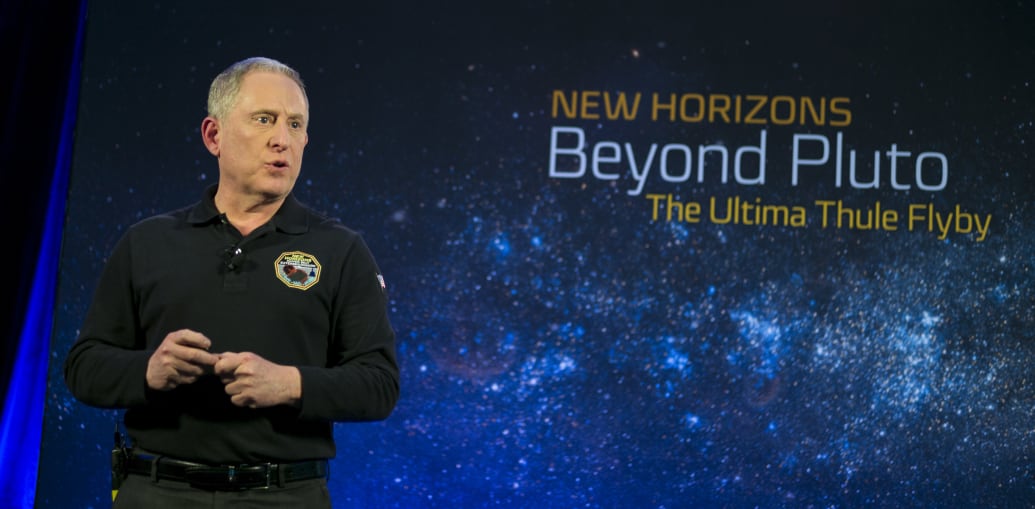

“He’s wrong about Pluto,” planetologist Alan Stern, principal investigator on NASA’s New Horizons mission, who sent a probe beyond Pluto in 2015, told The Daily Beast.

Alan Stern, principal investigator for NASA’s New Horizons mission, which sent a probe beyond Pluto in 2015, says Brown is “just plain wrong” about the retrograde planet.

NASA / Joel Kowsky / Getty

Fifteen years ago, scientists generally opposed, and later largely ignored, the radiation of Pluto. And they are now questioning many of the assumptions surrounding Brown’s campaign for a new ninth member of the Planetary Earth Club.

After all, for them nothing was right with the old ninth planet. Brown’s potential new planet would have to be at least number 10, if not number 50 or 500. More importantly, they warned, arbitrary bureaucratic interference with scientific definitions could cause serious damage.

Pluto’s kerfuffle “actually created a wedge between scientists and the public, and sends a terrible message – especially for this time – that science is made by decree on the basis of authority,” Mark Sykes, director from the Planetary Science Institute in Arizona. , told the Daily Beast.

The current controversy has its roots in a discovery 91 years ago, when astronomers at Lowell Observatory in Arizona accidentally first sighted the object they would eventually name Pluto. It was very far (about 3 billion miles), very small (less than a fifth of the Earth’s diameter), and dark.

It was considered, without controversy at the time, as a planet. After all, it was round and fairly smooth, which meant it had enough gravity to form, very slowly over billions of years. And he clearly had a complex geology. This matched the definition of “planet” that the Italian polymath Galileo Galilei proposed almost 500 years ago and on which almost all astronomers agreed in 1930 – and on which they still agree today. ‘hui.

With the discovery of Pluto, the solar system officially had nine planets: the fairly small inner planets Mercury, Venus, Earth and Mars and, on the other side of an asteroid belt, the mostly large outer planets Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune.

Pluto was the laggard and the outlier, lurking in the darkness of the Kuiper Belt, a ring of comets, asteroids, and ice that’s so vast and so far from the Sun that it’s still mostly a mystery.

The planet Pluto is depicted in a composite of four images from the New Horizons Long Range Reconnaissance Imager in July 2015.

Reuters

The programming remained the same for the next 76 years. Then, in 2005, Brown and his team detected another object in the Kuiper Belt, much larger than Pluto. NASA originally described this object, known as “Eris”, as the 10th planet in the solar system.

“After you find out about Eris and realize that Eris is more massive than Pluto, you have to do something,” Brown told the BBC in July. Rightly suspecting that there were more planet-like objects in the Kuiper Belt, he appealed to the Paris-based International Astronomical Union, the leading association of astronomers and other planetary scientists, to reconsider the definition of “planet” in order to prevent the accepted list from growing by the dozen or more – an expansion Brown at the time called “ridiculous.”

In August 2006, a small group within IAU surprised the rest of the Union and the world at large when, at the end of a week-long conference in Prague, they voted on a proclamation drafted in the haste rejecting Pluto’s status as a full-fledged planet.

The science base was screaming. The new definition of “planet” that the IAU has adopted, all with the aim of removing Pluto from the list and keep Eris off, demanded that a round body orbit our sun and too use its gravity to clear the space around it of asteroids and other smaller objects.

It was, in the minds of many astronomers, a bizarre definition. On the one hand, it ruled out Earth during its first messy aeons. He also left out thousands of confirmed orbiting “exoplanet” stars in addition to our own. (Catherine Cesarsky, who became IAU president just days after Pluto’s delisting and spent years defending the decision, did not respond to a request for comment.)

Stern said the IAU wants to keep the official list of planets in our solar system short so that teachers have no problem teaching the list and students have an easier time memorizing it – a reason he finds. “extremely reprehensible”.

“Do we have eight states in the United States so school kids don’t have to memorize all 50?” ” He asked. “Are we limiting the number of species? “

As a result of the quick vote, Pluto became a planetoid rather than a planet, just like Eris. And the discontent in the wider scientific community began, continuing to this day.

“I think the IAU’s demotion of Pluto was questionable,” Steve Maran, a former NASA astrophysicist, told The Daily Beast.

But Brown approved of the move. “Pluto would never have been called a planet if it had been discovered today,” he said in 2010 while promoting his book. How I killed Pluto and why he came.

The new definition of “planet” gave Brown the freedom to assess distant objects like Eris without having to make a case for their planet.

“I think Pluto as an example of a large object in the Kuiper Belt is so much more interesting than Pluto as a very strange planet on the outskirts of the solar system, unlike everything else,” Brown told Space. com in 2010.

Brown recently told the Daily Beast that he hasn’t changed his mind about Pluto. And he insisted that the outrage died down. “There are a few loud voices that continue to proclaim that Pluto should always be a planet, but almost everyone has moved on,” he said.

Brown has certainly moved on to another Something spin along the Kuiper belt which he believes deserves planet status more than Pluto.

Working with fellow Caltech astronomer Konstantin Batygin, Brown has tracked asteroids and other inhabitants of the dark periphery of our solar system. He and Batygin noticed that some of them seemed to cluster around a particular location in space up to 100 billion kilometers from Earth.

No planet is visible – it might be too far away and too dark – but the clustering of smaller, brighter objects could hint at the gravity of an invisible planet. “There is gravitational evidence for this,” Batygin told The Daily Beast. “But the search won’t end until we have a picture in hand.”

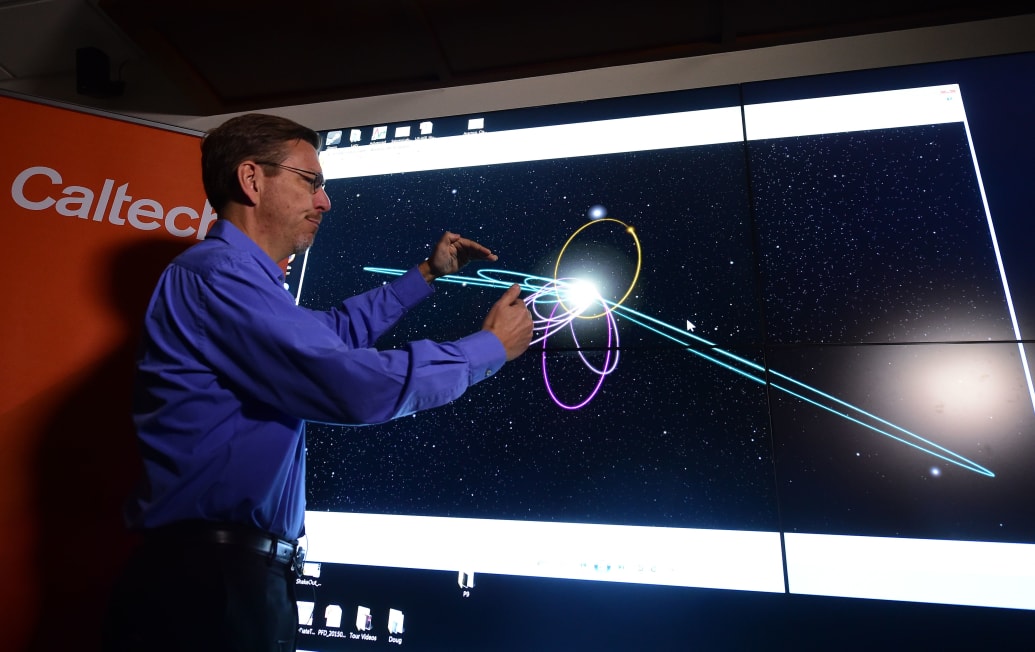

Caltech astronomer Mike Brown briefs the media on a potential ninth planet.

AFP via Getty

If Brown and Batygin can finally get a good look at all that might be there – perhaps using NASA’s soon-to-launch James Webb Space Telescope – it’s possible they could advocate for the IAU and other astronomical authorities recognize a new No. 9. Brown and Batygin’s summary of their initial investigation has been accepted for publication in Astronomical Newspaper.

Brown said he was convinced the discovery would obviously and uncontroversially be a planet. “It would be six times as massive as Earth and the fifth largest planet in our solar system,” he explained.

And many scientists agree with Brown that his discovery could be a planet, even under the IAU’s newly strict definition. Their complaint is that many objects there in the Kuiper Belt also warrant the tag, as does Pluto.

Astronomers never fully accepted the IAU’s redefinition of “planet” in 2006. Philip Metzger, a physicist at the University of Central Florida who studied the scientific literature for years after the radiation of Pluto, discovered that almost all scientists chose to simply ignore the IAU proclamation.

But the change was felt by the general public. Textbook writers and schools in particular took inspiration from IAU and dropped Pluto from their texts and lessons on the makeup of the solar system.

While Brown seemed to be hoping that the radiation from Pluto would allow him to explore the complexity of the solar system, it paradoxically had the effect of simplifying the design of the space by the public. And this narrowing of attention has come at a time when new discoveries, accumulating over months and years, reveal an increasingly bizarre and busy cosmos.

“Because of IAU, the public is isolated from the excitement of this mess! Sykes said. “The solar system is lousy with the planets!”

Brown’s own push for a new ninth planet underscores this reality. The simplified conception of space that prompted the downgrading of Pluto is a sort of tense fiction, which to many scientists seems every day more implausible.

[ad_2]

Source link